In The Mood for Urban Culture : The Romance Comics of Jan Mintaraga

Oleh Seno Gumira Ajidarma

The short version of this paper first published as proceedings from 2nd International Conference on Strategic and Global Studies (ICSGS 2018); part of publications in Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. Publication Date: November 2019. DOI https://doi.org/10.2991/icsgs-18.2019.10.

Editorial assistance for this long version was provided by Jennifer Lindsay. Published for the first time in borobudurwriters.id. The Indonesian language version, with much more research materials will be published in hard copy later.

Abstract:

The art of comic narrative lies in the combination of pictures and words. The romance comics that Jan Mintaraga (1942-1999) wrote and published from 1966-1971 in the early years of the New Order, reveal the hegemonic process of Jakarta becoming the representation of urban culture. The determination of power and ideological struggles formed the setting, plots, and lifestyle of urban culture in the making. Taking thirty-eight Mintaraga comic titles as source material to investigate social, economic, and political discourse, I find that the dialectic between the dreams and reality of the past can be useful for a consideration of urban life today. The experimental culture experienced at that period, including the role of niche-markets, is returning at the start of the digital age.

Keywords: Urban culture, hegemony, ideological struggle.

PART I

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1.URBAN RISING

At the beginning of the New Order, after the political disaster of 1965-1966, as the members of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) were hunted and massacred and the rest sent to prison for a long time, the Soeharto regime invited foreign investors to have a role in the development of Indonesia that was currently in a slump, as Ignas Kleden has described:

“… there were real reasons for special attention to economic development because right before the aborted coup of September 30, 1965, and in its wake, the economic situation was apparently beyond help. Inflation went up by more than 600 percent, there was a pressing scarcity of goods for everyday living. Just to get some rice, sugar or oil people had to stand in line for hours almost everyday, sometimes with much pain without gain. Eventually students went to the streets for continuous demonstrations.” (Kleden 2017: 1)

The change of political direction from the socialist tendency to capitalism was represented in the changing attitude of the youth, with the new consumerism. Life styles that were formally full of limitation, when even Soekarno in “Reinventing Our Revolution” (1964) connected the right and wrong of popular music with cultural imperialism, now become wide open to Western popular culture.

So, popular culture in the big cities could be said to be part of the growth urban culture, while urban culture itself, in some part is the consequence of the globalization process as supported variably by all the determinant factors in what Arjun Appadurai called the ideoscape, financescape, ethnoscape, technoscape, and mediascape (Appadurai in Simon During, 1999: 220). The phenomenal signs of urban culture will be examined in the media of comic books, from the genre of romance comics, especially those created by the comic artist Jan Mintaraga (1943-1999), which are the most popular in this genre.

All the signifiers construct an image or representation of the idea of an urban culture, theoretically there as a commodity, where the comic books in a way reflect the culture of the consumers too. The consumers bought a commodity product not only because of the financial economic factors, but also cultural economic as well, which, in John Storey’s terms, give the product an imposition of meaning (Storey 1996: 10, 26-7).

To begin this essay, the concepts of (1) popular culture, (2) urban culture, and (3) globalization will be defined first.

1.2. POPULAR CULTURE AND URBAN CULTURE: CONCEPTS

1.2.1. Popular Culture as a New Form of Culture

Popular culture, according to Storey, has more than one definition. There are (1) popular culture as folk culture; (2) popular culture as mass culture; (3) popular culture as opposed to high culture; (4) popular culture as an arena of hegemony; (5) popular culture as postmodern culture; (6) popular culture as the performance of identities; (7) popular culture as popular or mass art; (8) popular culture as global culture.

From these, I will refer to the fourth, sixth, and eighth as instrumental for my approach to the materials or objects of this survey. These three definitions, combined, will constitute this concept:

As an arena of hegemony, popular culture is the site where the subordinated group in society will always resist the discourse of the dominant group, that in the interest of being hegemonic should negotiate the discourse of the subordinated group. This is why that hegemony is a condition in process, and makes culture always in a situation of social consensus. Compromise equilibrium is the keyword that never guarantees a fixed meaning in the cultural site. That makes culture ideological.

This is also a process that makes identities in culture turn political, as they cannot be claimed as a natural expression but, as Storey explains, drawing on Judith Butler, are ‘performatively constituted’ and ‘made from a contradictory series of identifications, subject positions, and forms of representation which we have made, occupied, and been located in as we constitute and are constituted by performances that produce the narrative of our lives.’ Popular culture is a fundamental part of this process, as a characteristic of cosmopolitanism today.

At the same time, the concept of globalization has already transformed to the concept of glocalization, where translocal culture is opposed to territorial culture being a result of globalization as hybridity, because the complex relations of globalization are transforming localities: when the fragments after globalization destroys previous mode of culture supplies new resources for new forms of culture. The complex relations characterized this 21th century world, but the indicators were already seen decades before (Storey, 2007: 48-53, 91, 109-20).

1.2.2. Identity Politics in Urban Culture

Urban culture comes with urbanization. Most contemporary interest in the study of urbanization, Chris Barker says, ‘is in the political economy of cities especially as operates as an aspect of globalization’ as constructed by the struggle between globalization and glocalization’….‘Other approaches to the study of urban life’, Barker continues ‘put more stress on the cultural aspects of the city’ (Barker 2004: 203-4). So urban life is a cultural production process that becomes the symbol of modernity, but at the same time shows the ambiguity in the representation of modernity in everyday life.

Space in the urbanized city is constructed as an environment by industrial capitalism. The geography of cities is considered to be the representation of capitalism that creates markets and the controlled workforce. Some sociologists regard the power of capitalism as responsible for advantages of urban locations, including labour costs, tax concessions, and degrees of unionization. In a way, these factors that seem have no relation with cultural signs cannot be ignored as determinant of them.

The study of urban life also pays attention to city culture, investigating the existence of class, family life, lifestyle and ethnical aspects in everyday life. As only in the cities are there wide opportunities for work and leisure, the melting pot situation with a high degree of differences of people and cultural representations, provides the context for the importance of the survey. As Chris Barker points out, music, films, fashion, the lifestyle of traveling, to name just a view, are part of the media expressions where identity politics come in to play, and comic books are not an exception (Barker 2004: 204).

Barker’s work indicates how relevant a survey of Jan Mintaraga’s romance comic books can be to an understanding of urban culture:

The city can also be understood in terms of representation, that is, it can be grasped as a text. Representing urban life involves the techniques of writing—metaphor, metonymy and other rhetorical devices—rather than a simple transparency from the ‘real’ city to the ‘represented’ city. Representations of cities—maps, statistics, photographs, films, documents etc.—summarize the complexity of the city and displace the physical level of the city onto signs that give meaning to places. Representations of the spatial divisions of cities are symbolic fault lines of social relations and a politics of representation needs to ask about the operations of power that are bought to bear to classify environments. By revealing only some aspects of the city, representations have the power to limit courses of action or frame ‘problems’ in certain ways (Barker, 2004: 205).

So far, it seems clear enough how the survey of comic books could offer a better understanding of urban culture, especially as part of the cultural process of how locations become urban, in what Francis Mulhern describes as ‘the act of a metacultural discourse, which culture defined and speaks for itself.’ Mulhern explains that ‘[m]etacultural discourse is discourse in which culture addresses its own generality and conditions of existence. The position of seeing and speaking and writing in metacultural discourse, the kind of subject any individual ‘becomes’ in practicing it, is culture itself.’ (Mulhern, 2000: xiv).

1.3. ROMANCE COMICS AS URBAN NARRATIVE

-

- 3. 1. The Making of Comic Culture.

In the context of urban culture, is not really important to repeat the endless historical debate about where comic story telling, namely the sequential procedure of picture panels, really started. It is more efficient to find where the terms “comic book” begin. This search shows there is no doubt that the comic book format, the sequential narrative from the combination of pictures and words in panels, is an eligible part of the making of urban culture.

Michael Barrier, in his discussion of the history of the comic, refers to John E Vosburgh’s 1949 interview of Harry Wildenberg in which Wildenberg stated that he had invented the comic book back in 1932, when, Barrier writes, ‘his job was to concoct ideas that would sell color printing for the Eastern Color Printing Company in New York City, which printed a comic section for a score of newspapers along the Atlantic Seaboard.’ Vosburgh reported that Wildenberg said in the interview that ‘he was idly folding a newspaper in halves, then in quarters, so that the twice-folded paper occurred like a convenient book size, about seven by ten inches. For Wildenberg it is just reasonable to name it as comic book that would have 32 or 64 pages and make a fine item which distributes premiums. This idea gave birth in 1933 to a few premium comic books.’ (Barrier, 2015: 1).

However, the origin of the name “comic book”, as part of the process of commodity items production, is not the only reason that makes comic books urban culture. An earlier episode of that history is considered more likely as the playing an important part in making comic culture both a by-product and producer of urban culture itself. The first comic books were made up of reprints of Sunday comics pages. The next stage, though, as the cartoonist Coulton Waugh explains, was in May 1934 when the first American comic magazine in modern format, named Famous Funnies was placed on newsstands, independently of newspapers or premium connections (Waugh, 1947: 341).

The term “funnies” is only one step to the new term “comic”. What is important from this is that the narrative and the media where they were exist define the culture. The character Yellow Kid that appeared for the first time in Hogan’s Alley, a feature by R. F. Outcault in 1896, is not only recognized as the first sample of Oucault’s use of sequential narrative and speech-balloons in the Sunday page of William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, but the yellow color of his gown came from the new invention of the technology of printing machine. The new culture responded to the needs of the people of New York, the melting pot city of immigrants, to see something understandable in their ever changing surroundings, while the same psychological condition was true of the comic creators who tried to reflect something within the same social space.

Maurice Horn summarizes this combination of factors: citizens who were still getting to know each other, the four color possibilities provided by technology, and the harsh rivalries between Hearst’s New York Journal and Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World for hegemony of New York newspaper market which, Horn says ‘provided the ultimate catalyst in the synthesis of the disparate elements of narrative and illustration in a single whole.’ Competition over the Sunday supplement played a vital role in attracting the attention of the public, and also lured employees between the newspapers. This situation was the determining factor of the birth of comic-strips as a new cultural form (Horn, 1996: 16-21).

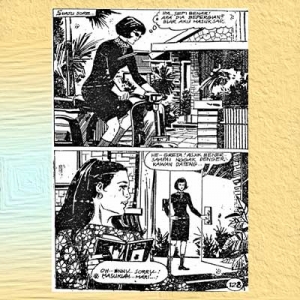

The character of this new form was, Horn describes:

… a narrative told in sequence of pictures, a continuing cast of characters, the inclusion of dialogue and/or within the picture frame, as well as by a dynamic method of story-telling that would compel the eye to travel forward from one panel to the next. This last distinction is very important, in that it separates the comics proper from most of the pictorial narrative of centuries past in which compositions were static and mainly serve as illustrations to the text or the captions. The comics are more than just a sequence of pictures in the same way that the movies are more than just a succession of photographs (Horn, 1996: 15-6).

With this kind of historical background, the comic book as the product of comic culture, that came into being from determinant factors that also constitute urban culture, proved to be the logical consequence as the media of the narrative that accommodated, intercepted, and expressed urban culture itself.

1. 3.2. The Rise and Fall of Romance Comics.

The romance comic is a genre of comic book that tells love stories of the youth in big cities. The first romance comic was published in 1947 and the last of the genre went out of print with Young Love #126 in 1977 (Barson, 2011: 8). That is what happened in the United States. Simultaneously, in Great Britain, from 1950 onwards an increasing number of girls comics blossomed, which reflected notions of ‘female interest’ current at the time. The first indications of this can be seen from 1920s to the 1950s, where there was already mention of the term ‘specific audiences’, meaning for girls, but the format was not a comic book yet. Roger Sabin, who has studied the emergence of this genre, points out that the love stories in the sequential narrative were a development from strips to pages, and only in 1964 did it establish itself as the same genre of romance comics in USA with the stories in Jackie, actually a magazine, that seems to be dedicated to the problems of young women in big cities (Sabin, 1996: 83-4).

With ideas of modernity as the new way of thinking, comics for young female readers captured the signs of superficial trends of modern lifestyle. This was not only what was depicted and written, as comic narratives are the fusion of pictures and words, but also the kinds of ideology imposed on the themes of the stories which aim to be modern. However we look at it, it is important to note that in the beginning all the stories functioned as ways for women’s magazines to give direction and advice about how the ideal woman should behave and be respected. In these kinds of magazines, young girls would share their relationship problems and experiences, and if they were interesting enough they would appear in the form of a graphic story. (Barker, 1989:160-95)

Using a young woman as the main character connected to the socio-political situation that women comprised half the population as market target. This can be gathered from the fact that although romance comics started in England in 1920 and romance dramas on radio began to be broadcast around the 1930s, it was only after W.W.II that the form became relatively established as a genre. This indicates there were factors resonating with the role of women after the war. According to Sabin, when servicemen returned, there was a drive to push women back into the home. (Michael Barson, 2011; Roger Sabin, 1996)

The momentum in 1947 for this romantic comic genre in United States is the start of a boom. Michael Barson points out that ‘in 1950 there were some 147 different romance comic titles being published, one of every four comic books then reaching the newsstand. At the height of their popularity, romance comics sold millions of copies each month, month after month.’ (Barson, 2011: 8).‘In Britain,’, Barson explains, sourcing Sabin, ‘the first of the boom comics had links with the early story papers, but while it is said that by the mid-1960s the boom in romantic comics was effectively over, recognizing that Britain had become the center of the ‘hip’ 1960s world, DC Thompson publisher attempted to produce a publication that mixed comics, women’s magazines, and the ‘pop’ papers: a new kind of swinging title for swinging times in 1964, and that is Jackie.’ (Sabin 1996: 81-3)

In the United States a sub-genre of romance comics emerged that specialized in an older readership, like young adults who seem to not go to school anymore. As Sabin describes,

“ …… the characters in Jackie did not go to school: they were wage earners, enjoying their ‘freedom’, and commonly shared accommodation with other hip wage earners in some large metropolis. They were physically and mentally more mature than the intended readership, and this was undoubtedly a major attraction. /The strips themselves tended to be romantic in an essentially traditional way, but with a ‘sophisticated’ veneer. ‘Catching a man’ was a top priority, and stories typically ended in the conventional final-panel snog. However, the artwork was more cinematic than most comics (….), and the plot usually had some measure of psychological depth” (Sabin, 1996: 84).

So, a comparison of the short history of romance comics in United States and Great Britain shows that with only a slight variant, the narrative is just the same genre, with the time line different. In United States, after the boom in the 1950s, as the 1960s gave way to the 1970s, the cancellation began and did not stop until Young Love, the most popular magazine of romance comic, went out of business in 1977 (Barson, 2011: 13). While in Britain, even though it is said that by the mid-1960s the boom in romantic comics was effectively over, Jackie just started as a phenomenon in 1964, and there is still analysis of romance comics from 1983 (Barker, 1989: 194).

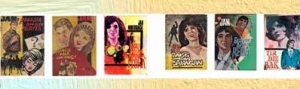

Romance comics in Britain from the 1970s

From the history and the narrative, it is valid to say that the romance comic is a representation of urban culture. It is also valid to say that from an examination of romance comics the process of becoming urban can be detected.

1.4. JAN MINTARAGA’S ROMANCE COMICS: JAKARTA AS A LOVE SCENE

1.4. 1. JAN MINTARAGA

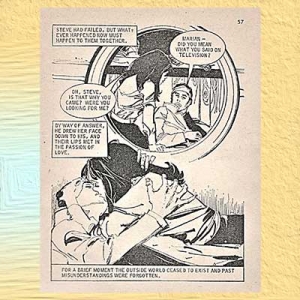

Jan Mintaraga’s real name is Suwalbijanto. Born in Pengasih, Kulon Progo, Yogyakarta in 8th November 1942, he finished elementary, secondary, and high school in Jakarta. He went on to study art in the interior design programme of the Academy of Fine Art (ASRI) in Yogyakarta until 1964, and then in the Art Department of the Bandung Institute of Technology until 1966. In these two schools of art Jan did not finish his study, but from 1965 his comics were already being published, with senior artists like Kosasih and Ardisoma as his mentors. He also drew covers and illustrations for popular pocket books published by CV Analisa and PP Rose. In the golden years of the Indonesian comic scene in the 1970s, Jan Mintaraga was considered one of the Big Five of the most popular comic artists, meaning in most in demand in the market. From this Big Five (together with Ganes Th, Hans Jaladara, Sim, and Zaldy) only two comic genres were represented, martial arts comics and romance comics. Of course one cannot deny that the superhero comics from Hasmi and Wid NS were selling well, also the hybrid of historical, romance, and action comics from Teguh Santosa; but the comic magazine Eres in Jakarta could not ask comic artists from outside the city to join, not to mention the technology of communication at the time.

Jan Mintaraga (1942-1999). (Foto: (c) DIAN HANDOYO/JAKARTA JAKARTA)

Comparing the three romance comic artists, Marcel Bonneff decribes Mintaraga as follows:

After much experiment, he chose to work on adolescent romance, and he was regarded as the most Westernized comic artist in style. His style was greatly influenced by American comic artists and his themes of his stories were often taken from comics that were published in Western countries where the culture drew his interest. However, he wanted to depict the life of youth in Jakarta, especially the life of those who had the possibility of profiting from economic progress. According to him, depicting ordinary people was not a good fit for adolescent romance that should be “romantic” and “easy” / … Undoubtedly [Mintaraga] is the comic artist who was most familiar with Western comics, and the only one that had the proper appreciation for comics and possibilities of developing them in Indonesia (Bonneff, 1998: 202).

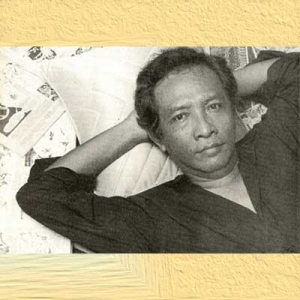

Bonneff finished his dissertation in 1972. When he interviewed Jan Mintaraga, the comic artist already had more than 100 titles under his name. He published two comic books each month, with the fee of Rp 60.000,-, and the title that rocketed his name was The Black Stain (Bonneff, 1998: 202).

Sebuah Noda Hitam (The Black Stain), 1968, one of the first successful titles

As The Black Stain or Sebuah Noda Hitam published in 1968 was one of the first successful titles by Mintaraga, it could be means that any reference to the mainstream of romantic comics is from the first rise of Jackie in Britain or the downwards trend of Young Love and others in United States. Compared to the research on Jackie or Young Love, there should be differences in the results, as the cultural background of Mintaraga’s romance comics is a different phenomena. Nevertheless, the method of research still could be the same.

It is not clear if the decline of the romance comics in Indonesia has the same cause, but if Young Love disappeared from the newsstands in 1977, and Jackie maybe in 1983, at first impression it seems as though Indonesian’s romance comics are like the second wave, their rise and fall following whichever was considered to be previous, the Britain or United States phenomena. But it should be noticed in advance that the socio-political background is different. Whereas pre- and post- World War II is the case for romance comics in the United States and in Britain, prolonged because of the hip culture that started in the 1960s, in Indonesia the context is different. Romance comics happen as the consequence of the rise of pop culture as a whole after the openness of the New Order to foreign investment, especially from Western countries, in contrast to the preceding Sukarno era; together with the cultural phenomena, like youth culture that included pop music, fashion, and comic culture at the time.

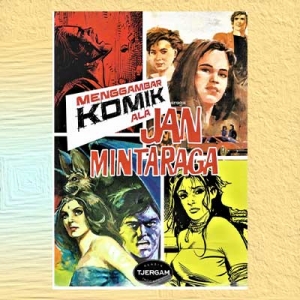

So, after The Black Stain made his name, Mintaraga continued steadily creating romance comics and in some way become an icon of that genre. In the heyday of the Indonesian comic scene in the 1970s, Mintaraga was not only productive as an artist, with the peak of achievement being the export of his comics to Malaysia, but he was also concerned about the existence and future of comic culture in Indonesia. In a 1970 essay, he defended the existence of the comic as entertainment if it could not be accepted as a pedagogical tool, because the aim of comic books is pleasure and the task of education is with the educators, despite the storm of opinion in society to crush comic books (Mintaraga, 1970: 4). In another essay, he thought that the fate of the comic book in Indonesia is like a bastard child cursed to be miserable forever (Mintaraga, 1983: iv). Beside discussing the current Indonesian comics situation, he also opened a drawing class in comic magazines like Eres, and even published a book for that purpose in 1986, Menggambar Komik ala Jan Mintaraga (Drawing Comics Like Jan Mintaraga) that was republished in 2016.

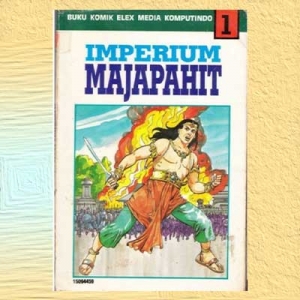

Mintaraga still published the short Balada Sebuah Cinta (Ballad of Love) in 1980, but he had by then also been working on other genres, like superhero and martial arts, because romance comics were already declining. Relating to the downsize of every genre in Indonesian comics in later years, Mintaraga was always involved in the struggle to return the Indonesian comic book to the market. The comic market itself, even the space of the entertainment industry was becoming increasingly crowded, still alive happily with foreign comics, from Europe and Japan, that were translated into Indonesian. The struggle was in publishing Indonesian orientation comics that were thought to be original and maybe even superior to imported comics. At this time, Mintaraga worked on a serial of the Ramayana in 1985 and the historical series of Imperium Majapahit (Majapahit Empire) in 1994. This is further evidence of his engagement in the struggle to keep the Indonesian comic alive.

Menggambar Komik ala Jan Mintaraga (Drawing Comics Like Jan Mintaraga, 1986/2016)

Imperium Majapahit (Majapahit Empire, 1994)

It is not so difficult to realize that the change in the economic policy by the New Order regime after 1965 to invite foreign investment, had an enormous effect on the rise of popular culture, so that the dynamics of the market showed the rise and fall of the romance comics in the Indonesian comic scene. After the golden years of the 1970-1980 decade, Mintaraga said in an interview from 1992, that even before he became “somebody” at that time he was still a “nobody” (Rentjoko, 1992: 30). However, by the time Mintaraga passed away in 1999, he was remembered as the champion of romance comics that live forever in the collective memory of the 1970s generation (Ajidarma, 1999: 65).

1.4. 2. The Urban Love Scene: Jakarta as an Icon

In romance comics, the plot always pursues a question: will the couple be united in the end? So after the first introduction, when a promise of happiness seems very reasonable, the plot should give as many obstacles as possible, which each of the couple should go through, successful or not, before reaching the end of the story.

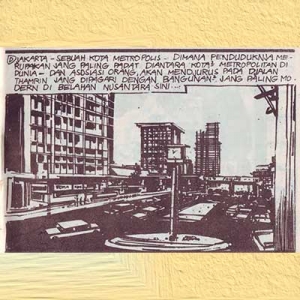

Urban Jakarta after 1965 was still in the first steps of the urbanization process.

This kind of plot is not yet the sign of an urban culture, because the same plot could happen anywhere in the world. It is only urbanized with the background of a big city, with typical life style, fashion, language, and world view that should be different from traditional culture. In the case of Mintaraga’s romance comics, as urban Jakarta after 1965 was still in the first steps of the urbanization process, the distance from the previous cultural life of the urbanites, and also with the previous Jakarta itself, could not be too far. It is not impossible to guess that the urban environment in Mintaraga’s creation is not a copy of the reality but a dream of an urban city as the future of Jakarta, inspired by the popular culture phenomena.

Comics become independent as a text of urban culture, or else the urban city becomes a text that should be treated as a representation. In this view, Jakarta in the comics is going to be an independent world, as a contestation of the present time of Jakarta when the artist is narrating those urban love stories of the youth. In other words, Jakarta in the comics is an icon of an urban Jakarta. “Jakarta Love” or “Cinta Jakarta”, to take the term used by a comics researcher, regarding the set where all the love stories happened (Atmowiloto, 1979: i-x).

This setting of Jakarta is part of the making of the urban, as Firman Lubis records in his memoir of the 1970s:

Besides allowing Jakarta to be a gambling venue, the municipal regional government of Jakarta during Ali Sadikin’s governorship gave permits to open many entertainment venues like night clubs, bars, discotheques, massage parlors, and billiard parlors, which were previously unknown to Jakarta’s citizens. Many of these entertainment venues opened in public areas or commercial business districts like Kota, Jalan Gajah Mada and Hayam Wuruk, Pasar Baru, Jalan Sabang, Jalan Blora, Blok M and Taman Ria Ancol. Actually, most of these entertainment venues also functioned as prostitution venues, especially the massage parlors, night clubs, and discotheques. That is why the term “complete massage”, meaning massage complete with sexual intercourse, became familiar. Besides that, the sex industry also operated in hotels and motels that grew in 1970s Jakarta (Lubis, 2010: 69-70).

Urban culture become a source of inspiration for comic artists.

With all the excesses of these entertainment businesses, the development of Jakarta as a metropolitan city that generated an urban culture become a source of inspiration for comic artists, and gave some identity to Jakarta’s Romance genre. The characters in comic books created by Jan Mintaraga, Sim, and Zaldy, the three most popular romance comic creators, are not only full of high school or university students as the main characters, but also professions from the night life like night club hostesses or female singers that often have love relationships with wealthy older men. As this is only some part of the scene, it is interesting to investigate further the kind of urban culture that is represented in the romance comics, to catch how an urban culture was developing in the early stages.

2. BEYOND REPRESENTATION: AN URBAN FACE AS A PROBLEM

2.1. As Mintaraga himself admitted, he wanted to create comics about the contemporary life of young people (Soelin, 1970). His romance comics are thus like a window to an urban process. The nature of youth culture in the first years of the New Order era, that always followed or even created the latest fashion and life style, gives an opportunity to investigate how the works of Mintaraga can appear as an urban culture text of his time.

2.2. Considering that popular culture is always in the process of change, this also means that the comics were a site of negotiation of ideological struggles, with all the workings of power as a factor. An examination of the signs of identities can lead us to recognize how the world outside the comics has determinant factors to constitute the narrative, and simultaneously how these romance comics had some effect on that world.

3. FINDING THE PATTERNS: THE CONCEPTS

The method first used by Martin Barker in 1983 for his research on Jackie, the popular magazine with its romance comic inside is used here because of the practicality and effectiveness to catch a pattern from the research material, namely romance comics in both cases.

Barker has pointed to a number of typical story-features, which involve distinguishing different kind of motifs within the stories. By a ‘motif’, Barker means a small-scale organizing feature which enables a typical move to take place, or a typical relationship between parts to be suggested. These different kinds of story-motifs are both sequentially and hierarchically organized. I reproduce Barker’s helpful distinctions in summary here:

- Sets. ‘These are typical places for kinds of encounter: they come endowed with certain possibilities. For example parks, coffee bars and discos are territories where new relationships can begin. They are places of accidental encounters….open countryside is less commonly the place for this kind of accidental encounter. … if such an encounter takes place in such a wild place, it will somehow be a wild encounter. Places, in other words, come coded with possibilities of relationships. …. A ‘set’ on its own is a low-level motif, merely broadly indicating a field of possibility of encounters. On its own it carries little or no emotional charge.’

- ‘Story-enablers. ‘Of these the most obvious is flash-back, which enables us to see a problem and work back to its cause and outcome. A story-enabler is a procedure whereby the romance-agenda is helped into story-form. A quite different example of a story-enabler is a switch in narrative perspective… ‘Story-enablers’ facilitate the assembling of tension and uncertainty, but on their own do not determine the content of that tension.’

- ‘Theme-markers. ‘These are motifs which provide points of tension, but which also incline the story to resolve itself in particular direction. For example: a separation between boy and a girl often sets off a series of events through the rest of the story. Suppose a character gets a new job, whether explicitly or implicitly, the question will have been posed: will s/he return to the relationship? … ‘Theme-markers’ begin to organize the movement of events through the stories, and can condition the use of sets and story enablers.

- ‘Emotional foci. ‘These are moments of high drama which mobilize the energy of the stories… ‘Emotional foci’ provide a rhythm of movement through a story, between high and low tension (Barker, 1989: 190-1).’

Applying his framework to his analysis of Jackie, Barker proposes that ‘Jackie’s agenda of questions largely determines the forms and combination of these motifs. They make possible the translation of romance into stories revealing the meanings of ‘love’, its problems and pleasures.’ He goes on: ‘They take these forms precisely because that agenda is concerned with the logic of emotions.’ Barker then proposes that ‘the more tightly organized a story is, the more meaningful it will be to its readers. By ‘tightly organized’ I mean that the lower-level motifs become embraced with the higher level motifs.¹

Barker tests his proposition in his review of some feminist critique of Jackie, which he says forces feminist ideology on the material.² In my current survey of Mintaraga’s comics, following the same routes of Barker’s research, the target is to view, investigate, and find the movement or the flow of becoming urban, as can be read from the useful distinctions he has provided. To reiterate, the signs of the process of becoming urban is the target of the survey, employing the semiotic concept of sign as in Tim O’Sullivan’s summary:

A sign has three essential characteristics: it must have a physical form, it must refer to something other that itself, and it must be used and recognized by people as a sign. Barthes gives the example of a rose: a rose is normally just a flower, but if a young man presents it to his girl friend it becomes a sign, for it refers to his romantic passion, and she recognizes that it does / Signs, and the ways they are organized into codes or languages, are the basis of any study of communication. They can have a variety of forms, such as words, gestures, photographs or architectural features. Semiotics, which is the study of signs, codes and culture, is concerned to establish the essential features of signs, and the ways they work in social life.³

Clearly, all these concepts are useful as tools for the investigation and examination of Mintaraga’s romance comics as the representation of the growth of an urban culture. The concept of sign, O’Sullivan suggests, should be pursued by three orders of signification, as follows:

- ‘The first order of signification: denotation. The simple or literal relationship of a sign to its referent. It assumes that this relationship is objective and value-free. The concept is generally of use only for analytical purposes; in practice there is no such thing as an objective, value-free order of signification except in such highly specialized languages as that of mathematics: 1+1=2 is a purely denotative statement.’

- ‘The second order of signification: connotation. This occurs when the denotative meaning of the sign is made to stand for the value-system of the culture or the person using it. It then produces associative, expressive, attitudinal or evaluative shades of meaning. Connotation is determined by the form of the signifier: changing the signifier while keeping the same signified on the first order is the way to control the connotative meanings. Connotation works through style and tone, and is concerned with the how rather than the what of communication.

The second order of signification: myth. The term myth refers to a chain of concepts widely accepted throughout a culture, by which its members conceptualize or understand a particular topic or part of their social experience. These myths are arbitrary with respect to their referents, and culture specific. Myths are conceptual and operate on the plane of the signified; connotations are evaluative, emotive and operate on the plane of the signifier.’ - ‘The third order of signification: ideology. Fiske and Hartley (1978) suggest that the connotations and myths of a culture are the manifest signs of its ideology. The way that the varied connotations and myths fit together to form a coherent pattern or sense of wholeness, that is, the way they ‘make sense’, is evidence of an underlying invisible, organizing principle—ideology. Barthes identifies a similar relationship when he calls connotators (the signifiers of connotation) the rhetoric of ideology; Fiske and Hartley suggest to think of ideology as a third order of signification.4

However, it is also needed to add the concept of meaning, that becomes the final stage in the analysis:

‘Meaning is the import of any signification and the product of culture./ Meaning is the object of study, not a given or self-evident quantum that exists prior to analysis. Hence meaning should not be assumed to reside in anything, be it text, utterance, programme, activity or behavior, even though such acts and objects may be understood as meaningful. Meaning is the product or result of communication, so you will doubtless come across it frequently. / As meaning becomes the product of culture, there are three meaning system that explain how people make sense of their social world: (1) the dominant system: endorses the current structure of social, economic and political relations, and enables people to understand their social location within the existing distribution of power, wealth and jobs. It produces in the subordinate class deferential or aspirational response: deferential responses are made by those who accept their position, and aspirational by those who seek to ‘improve’ it within the same system; (2) the subordinate system: this accepts the overall dominant system, but always particular groups the right to demand a better position within it. It produces negotiated responses which frequently attempt to exploit the system to the advantage of a particular group or class within it; (3) the radical system: this rejects the dominant system and proposes an alternative one opposed to it. It thus produces oppositional responses./ The systems produce three equivalent codes for the decoding of the text – the dominant hegemonic, the negotiated, and the oppositional.’5

I will use these concepts of meaning as an instrument of evaluation following a survey to find the general signification of urban culture by the comics. The more abstract discourses that leave the physical signs behind, will be the second step of the following survey.

4. TWO STEPS OF READING: THE METHOD

This materials of the survey are 38 titles of romance comics by Mintaraga. Only two of these titles are outside the 1966-1971 period as the focus of the survey. While one title from 1972 could included to the period, titles from 1980 and 1994 are useful for a comparison regarding the time period. Classification will be made after the distinctions, that is, reading with attention to the (1) sets, (2) story enablers, (3) theme markers, and (4) emotional foci, with an aim to recognize the signs of urban culture.

All the titles will be investigated as chronologically as possible to sense the development over time from the four distinctions that each of them individually, then together, forms the signs. These signs as a representation will be evaluated and examined to constitute an understanding of an urban culture in the making, that is also a means to find the meaning.

The methods of survey will be: (1) description of the comics with four distinctions to find a general signification (2) evaluation and analysis of the meaning, until the survey comes to the findings and formulates the results.

5. INTO WORDS AND PICTURES: VIEWING AND INVESTIGATION

Below, titles are given, followed by the number of pages and the year of creation or publication. The synopsis of the plot will be the first description followed by analysis as far as the concept tools can be applied to the text, then an evaluation closing with a conclusion on the findings. The general analysis will be made after finishing the investigation of all the titles.

As this is only a preliminary examination of the romance comics of Jan Mintaraga, there is no specific criteria of the titles chosen here other than they are in the genre of romance comics.

The titles found are:

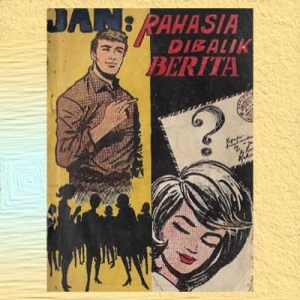

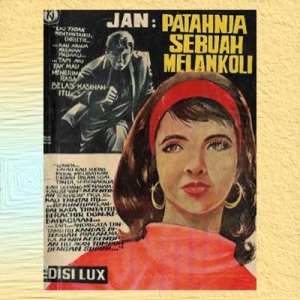

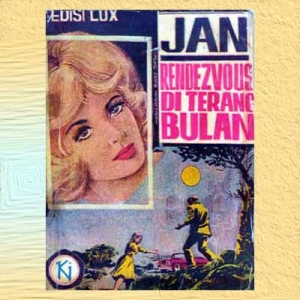

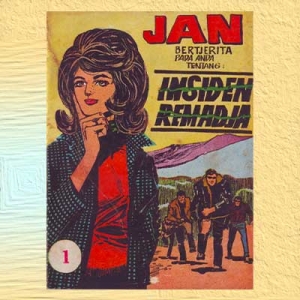

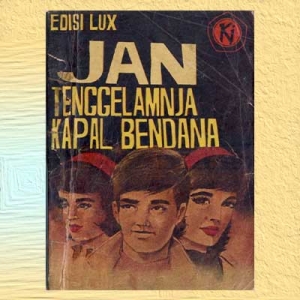

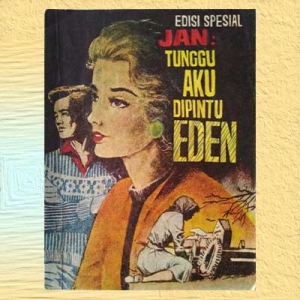

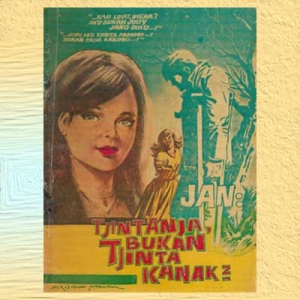

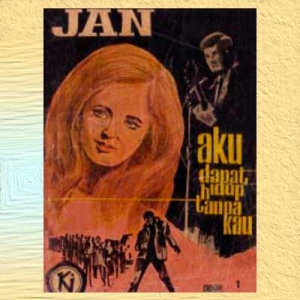

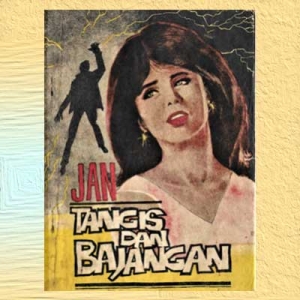

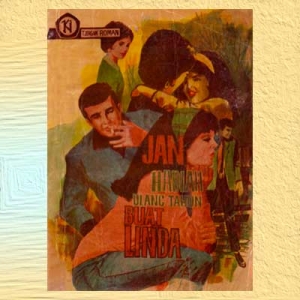

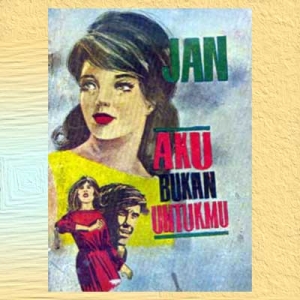

(1) Rahasia di Balik Berita (The Secret Behind The News) ( 31/196.); (2) Di Langit Ada Bintang! (There is A Star in The Sky) / 33/1966); (3) Patahnja Sebuah Melankoli (The Break of a Melancholy ) /65/1966); (4) Rendezvous di Terang Bulan (Rendezvous in The Moonlight) /64/1966); (5) Berakhir dengan Suatu Kepahitan (Ended With Bitterness) (/63/1966); (6) Insiden Remadja (The Teenagers Incident) 61/1966); (7) Tenggelamnya Kapal Bendana (The Sinking of The Ship Bendana) (/62/1966); (8) Tunggu Aku di Pintu Eden (Wait for Me at The Gate of Eden) (/58/1966); (9) Tjintanja Bukan Tjinta Kanak-Kanak (Her Love Is Not a Child’s Love) (/64/1967); (10) Aku Dapat Hidup Tanpa Kau (I Can Live Without You) (/62/1967); (11) Tangis dan Bajangan (Weeping and Shadows) (63/1967); (12) Hadiah Ulang Tahun Buat Linda (A Birthday Present for Linda) (64/1967); (13) Aku Bukan Untukmu (I am Not for You) (/64/1967); (14) Melodi di Achir Tahun (End of Year Melody) (64/1967); (15) Sebuah Noda Hitam (A Black Stain) (319/1968); (16) Pangeran Impian (Prince of Dreams) (64/1968); (17) Affair Lembah Tali-Putri (The Tali-Putri Valley Affair) (64/1968); (18) Roda (The Wheel) (162/1969); (19) Tonil (The Stage) (144/1969); (20) Kau Belum Wanita Flora (You Are Not a Woman Yet, Flora) (161/1969); (21) (Si Djalang (The Wild One) (165/1969); (22) Soneta dari Sudut Piano (Sonnets from The Piano Corner) (160/1969); (23) Telur Di Ujung Tanduk Egg Crowning a Horn) (159/1969); (24) Tembok (The Wall) ( 64/1969,110/1970); (25) Antara Dua Eva (Between Two Eves) (161/1970); (26) Kelana (Wanderer) (224/1970); (27) Pulang dari Bukit (Back from The Hills) (192/1970); (28) Lagu yang Terpotong (Broken Song) (254/1970); (29) Pauline (128/1971); (30) (Pemuda dalam Tjermin) Young Man in The Mirror (190/1971); (31) Sesudah Badai Reda (After The Storm) (380/1971); (32) Di Antara Serigala (Among Wolves) (192/1971); (33) Anita (128/1971); (34) Rumah Djahanam (The Damned House) (/320/1971); (35) Terdjebak (Trapped) (256/1972); (36) Hancurnya Sebuah Tirani (A Tyranny Shattered) (34/1979 [1969]); (37) Balada Sebuah Cinta (Ballad of a Love) (/96/1980); (38) Fajar Menyingsing Juga (The Dawn Also Rises) (46/1994).

5.1. Romance Comics, Urban Culture: 38 Investigations.

-

- Rahasia di Balik Berita (The Secret Behind the News) (31/196.).

Lilya is just one of many women employees in an office. Juda, the director, young and single, is the favorite of all the women, Lilya included. Tuti, who shares a room with Lilya, had a boyfriend, but observing Lilya’s concern for Juda, she tries to match them. Then, in a swimming pool, Juda find Lilya very attractive. Juda asks Lilya to come to a party, where he introduces her to his mother. However, Lilya is very disappointed when at the office Juda treats her as a secretary again, just like any other employee, until she feels sick and does not want to go to the office. Meanwhile, at the office, Tuti, another secretary, unintentionally reads Juda’s mother’s letter, that informs Juda about Lilya. Juda’s mother gives her blessing if Juda wants Lilya to be his wife. Lilya does not really believe this, until Juda comes and asks her to marry him. Notes: Happy ending (H).

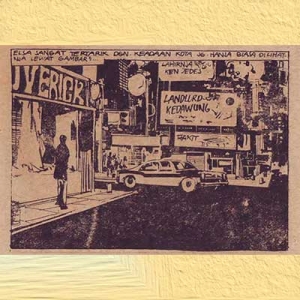

Sets: The office, outdoors, or dormitory room looking very clean and the interior design, referring to Art Deco, perfectly applied, seems modern. There are places to meet, like the swimming pool, and business districts signified by billboards give an image of modernity. Th surroundings appear to be the perfect background for up to date fashion and hair styles.

Story-enablers: The swimming pool scene, where Juda is enthralled by Lilya, make the story move forward, but Tuti’s previous comments, that a woman needs a man through life, is the enabler that constitutes the plot.

Theme-markers: Lilya apparently thought Juda not good enough as a human being, then feels sick, and cannot go to the office, while it is obvious that Juda is really attracted to Lilya.

Emotional-foci: There is an uncertainty when Lilya still at home, reading a book, not knowing what to do after the information from Tuti. The tension here, in that one panel only, is up and down.

Signification: Everybody works and prospers here, with signifiers such as good looks, established clothes and lifestyles, and nothing the opposite as unhappiness, except if a woman doesn’t find her match. So the urban creates a class with its semiotics signifiers, without changes in attitude, as women are still dependent on marriage, and a mother still makes the final decision of who deserves to be her son’s wife. Juda’s mother is actually especially invited from the country.

2. Di Langit Ada Bintang (A Star in The Sky), (33/1966).

Dienah and Jussac are neighbors that became best friends in their adolescent years. They are still close to each other at the same university, but then they feel something different. The status of best friend appears to be the obstacle to the fact that they love each other. When Jussac is attracted to Indri, Dienah tries to suppress her feeling, especially while she helps Jussac writes a love letter to Indri, and it works. Jussac then goes out with Indri. But one day Jussac and Dienah find out that Indri has a boy friend. Jussac’s heart is broken, and when Dienah tries to accompany him, Jussac says that Dienah can’t understand him because she has never loved anybody. Dienah then reveals her feelings for Jussac, and Jussac feels the same for Dienah He shows Dienah that there is a star in the sky. H

Sets: Housing and university became the main sets, but there are also outdoors of the business environment with trade names on the stores. All the places seems clean all the time, and the persons involved in the story are good looking students with fashionable clothes.

Story-enablers: The moment Jussac says that he is attracted to Indri is the switch that drives the story forward until the end.

Theme-markers: Jussac and Dienah see Indri with another man on the street. The following switch escalates the tension.

Emotional-foci: Jussac says that Dienah will never understand him, since Dienah has never fallen in love with anybody.

Signification: Even though at the end Jussac and Dienah become a love couple, the fact that they know each other from childhood, and the following story, does not guarantee that eternal love will survive in the background of urban culture. The city is threatening, not a safe place for love. This is the consequence of attracting many people to come to town.

3. Patahnya Sebuah Melankoli (The Break of a Melancholy) (/65/1966).

This title is from the cover, in the splash page the title is Akhirnja Sebuah Melankoli (The End of a Melancholy).

Chandra is a film star. One day he stars in movie of a story written by Christie, his favorite novelist. After they are introduced to each other, Chandra and Christie seem to get along really well. However, this fact makes Wanda, his film star counterpart who is still young, very jealous. Meanwhile, Chandra himself has had a bad experience with alove relationship, when his previous girlfriend before left him. Besides, related or not, his bad habit of smoking and lung sickness makes him feel that women only pity him, so he always avoids relationships, with Christie included. However, when Wanda appears at the sanatorium aftera period of 18 years, Chandra tells her that there is light in his life. H

Sets: The environments are destination places for youth, but most are film shooting locations, then the sanatorium where, everything is outdoor scenery; as opposed to urban space that appears as an exterior only once. The rest are interiors of restaurants and houses, with signs of the modern style.

Story-enablers: The flash back is the story of Chandra’s broken heart which makes him not really interested in building a serious relationship with any woman. But there is also the background that he came from a poor family. A similar flash back also happens with Christie, even the story which Chandra played was from her experience.

Theme-markers: Wanda’s love for Chandra has many obstacles; if not the existence of Christie, then Chandra’s mentality, and her own young age; escalate the tension regarding innocence.

Emotional-foci: Chandra can not have a peace with himself in the dialogue with Christie, who he thinks only pities him—while the results for Wanda that come later is the opposite.

Signification: Young love is just like the young urban dream—where everybody should be successful in leaving the past behind, love should be responded to positively, and rejection or break up is wrong. This value determines the drama.

4. Rendezvous di Terang Bulan (Rendezvous in The Moonlight) (64/1966).

This is a story about a very young love that does not end, because one of the couple dies. Iwan is a racer and at the same time a student of economics at university, where he meet Lolita the stewardess. They fall in love but find it very hard to express it. When the time comes to speak openly, Lolita asks Iwan to stop racing. Iwan agrees, except for one last race. It is not told that Iwan dies in the race, but Lolita dreams that Iwan asks her to go to their usual rendezvous place. When Lolita comes there, she finds only Iwan’s grave. Notes: Unhappy ending (UH).

Sets: Starting from a race venue, Iwan meets Lolita who brings her two nephews and her parents. In 1966, this kind of venue was a new attraction, that leads to the fashion of the spectator, including the characters who live in luxurious houses, depicted with the latest style and interior design.

Story-enablers: Iwan and Lolita, each thinking of the other, ask themselves if the other loves him or her.

Theme-markers: When they find that they really love each other, the two separate because of their job, Iwan with his intended last race, and Lolita flies to Japan as a stewardess. When she comes back, her parents have doubts about telling her about the fate of Iwan, which they already know.

Emotional-foci: The rhythm is slow at first, when the plot still provides the condition of unguaranteed love; then becomes dynamic when there are uncertainties about the future of the two lovers.

Signification: As the set shows only modern vehicles and surroundings, and no traditional becak (pedicabs) at all in Jakarta, which is not realistic at the time, it makes the impression that the narrative is delusional., The story enabler is also tolerant to the very young and not a mature love story. The separation, as theme marker, gives way to their idyllic life destroyed by the power of destiny, and that gives an emotional foci of uncertainties that is not yet an urban spirit.

5. Berakhir dengan Suatu Kepahitan (Ended with Bitterness) (63/1966).

Sani, a university student, meets Sari, a popular singer. Nothing happens until Tetty, a girl with glasses who Sani likes, arrives. But it is from Tetty that Sani hears that Sari is interested in him. After some difficulties, Sani and Sari go steady. Then, while Sari is busy on tour as a singer, Sani has a study tour to Surabaya, and exchanges photos with Ida, a local student. Sani becomes disappointed by the gossip about Sari in the media, namely that she had a relationship with member of the group Sari isalso suspicious about the photo of the Surabaya student. After all their struggle to keep their relationship, at the end they break up. UH

Set: The reader never sees the panoramic Jakarta or Surabaya, or even the campuses of these students, but finds the modern interior design of houses with paintings on the wall where the characters live their drama. House interiors are a rare opportunity to show the social condition. There is also an interior of a book store. The outdoors scenery seems like the typical destination for lovers, with trees and mountains as a background. Empty spaces fill the outdoor scenery in the city.

Story-enablers: While Tetty is the cause of the meeting, other people are suspiciously subjected as intruders on the relationship.

Theme-markers: Immaturity makes the problem heavier than it should be. When an easy problem should be solved, immaturity takes the opportunity away.

Emotional-foci: Actually the protagonist male character, the I that narrates this story, has a problem with himself regarding the continuation of the relationship. This characteristic of instability guides the tension.

Signification: The incomplete scenery of the urban city, together with the incomplete maturity that is really needed for the stability of the couple, reflects the very young urban narration from the first years of what would became a rapid changing society of Jakarta.

6. Insiden Remadja (The Teenagers Incident) (61/1966)

There are two music bands, led by Boy and Jopie. In Jopie’s band there is Tatie, his sister, as the singer. Boy and Tatie are interested in each other, but this is interrupted by the fact that while the two bands are competitors, the situation is infiltrated by Hamdan, an arms smuggler who is disguised as a businessman and who is also attracted to Tatie, his employee. He uses his henchmen to mastermind a conflict between the two bands while kidnapping Tatie and taking her to the mountain where the insurgents are based. A subplot is then added, that one of the henchmen is an ex-military man who has no job in the new era. After a spell with Hamdan, he turns in his employer, and shoulder to shoulder with Boy releases Tatie from the kidnappers. H

Sets: Music bands at the time played for birthday parties at private houses, and the interior design, in any house, is modern. There are also offices, restaurants, and the outdoors as well, in the city and the country.

Story-enablers: The interest of Hamdan for Tati enters the problem of Boy and Tatie. The tension between Boy and Jopie is not finished yet, but the enabler is the information that Hamdan smuggles arms for the insurgents in the mountain, while he is also part of them.

Theme-markers: The character Ribut, the marginalized ex-military man, first appears like an antihero, who only works for money, but then proves that this is not the case, so that the plot can give way to Boy as the hero. In the end, it looks like the relationship of Boy and Tatie has just started.

Emotional-foci: At first the conflict of Boy and Jopie seems to escalate the tension, but the rebelliousness of Ribut seems to steal the show, while the previous scene that shows the smuggling business already takes the romance plot in the direction of action comics.

Signification: As urban icons like music bands, the young generation, and private parties begin to blossom in this genre, the shadow of political problems from the past still haunt, effectively making this story very different from all the others. The transformation represented in pictures and words comes as a clear sign of the discourse of the first years of the New Order.

The shadow of political problems from the past.

7. Tenggelamnya Kapal Bendana (The Sinking of the Ship Bendana) (/62/1966).

Arman and Annie are falling in love. This relationship is interrupted by Anna, Annie’s identical twin sister,, who never reveals her true identity to Arman while Annie is out of town. Arman is already feeling close to “Annie” when Annie uncovers the fact to him. The identical factor makes Arman feel confused and guilty, as though there is no solution, , until Annie gives up and follows Anna back to Medan on the ship Bendana. Arman is ready to reunite with Annie when he reads the news, that Annie is one of the victims when the Bendana sank.. It turns out, that it is not Annie but Anna who is the victim. Arman still thinks Annie is Anna when they meet, and he blames her as the trouble maker in the relationship, but the story finishes with a happy ending. H

Sets: As always happens with house design, exterior or interior, is modern architecture. Unlike other titles, in this title there are no cars at all, only some views of the ship. Another contrast, there is one becak (pedicab) as the only vehicle seen in front of a house There are also depicted what were thought to be places of destination for young people, such as parks and empty roads surrounded by luxurious houses..

Story-enablers: The flash-back useful in this story is the reflections of Annie about Anna, that her twin sister is not yet out of her puberty phase, so that she still plays games with relationships with men. This background is important when Anna confesses to herself that she really loves Amran, her sister’s boy friend.

Theme-markers: Tension escalates when Annie finds out about the Anna-Amran relationship going on, under the disguise of Anna as Annie. She interrogates Amran about his the love, whether it is for Anna as Annie, or Anna as Anna. Amran’s instability in making decisions escalates the tension higher.

Emotional-foci: The mistaken identity of Anna as Annie for Amran, continued by the mistaken identity of Annie as Anna, who now Amran really hates. When he angrily talks to Annie thinking it is Anna, it turns out to be a high-drama. The rhythm is built through the series of mistaken identities and confusion.

Signification: How far can identical twins confuse someone in a long standing relationship and not be only an accidental blink? It seems like love is connected only to the physical, and also the modernity in becoming urban.

8. Tunggu Aku di Pintu Eden (Wait for Me at The Gate of Eden) (/58/1966).

Chanifah is Herman’s past love. When Herman meets Santy, he feels that Santy can replace Chanifah. Actually, Herman really loves Santy as Santy, not as a replacement of Chanifah who is physically very similar. However, Santy, who is in love with Herman, thinks that in Herman’s mind she is just Chanifah. She can not stand her own thoughts. The impossibility of marriage makes Herman sick and he dies. In her tears of regret at Herman’s grave, Santy asks Herman to wait for her at the gate of Eden. UH

Sets: The interior design of the modern houses here are dominant, as the relationship begins inside the house. Parks outside town in the mountains seem like the typical destination for young couples. Cars are seen on the street that look crowded. The surroundings and the fashion are related, detailed in every motif. Abstract paintings in the studio are mentioned as an expression of weirdness or something unusual.

Story-enablers: The intrusion of Chanifah’s shadow into the relationship is a problem that in the end can not be solved. Even though Santy willingly takes care of Herman, she keeps telling herself she is not going to marry him.

Theme-markers: The motif that determines the story is Santy’s rejection union with Arman, after a very good relationship with him. The conflict is not just that Arman really needs Santy, but that even though Santy confesses to herself that she is in love with Arman, she feels it is not right to continue the relationship.

Emotional-foci: When a friend gives Arman letter to Santy, there is no sign that he has already passed away. Santy’s regrets and the consideration that marrying Arman is the right thing to do, but that now it is too late, bring quite a tension, that is in a way really unexpected.

Signification: The very sentimental love, that a separation could make someone die, shows the early attitudes in the urban city as a moral legacy from the past; while new professions like singer and painter come to exist as a normal job. Physically the urban environment in the comic is an imagined ideal, but the attitude towards love is not an urban practical love yet.

9. Tjintanja Bukan Tjinta Kanak2 (Her Love is not a Child’s Love) (64/1967)

Judy (Indonesian modern spelling Yudi, m) and Viera (f) love each other. One year older than Viera, Judy is going to university first to study economics, even though in Viera’s opinion, his talent shows that he would be better studying fine art. Meanwhile, Viera’s mother does not agree with the relationship, because socially Judy is not from the same class. So she tells Viera to be serious in her study, and make distance from Judy. After Viera tells Judy about this problem, Judy realizes he is psychologically in trouble, working hard to study and paint simultaneously, so that he fails his economics study. Unable to find peace, Judy disappears, moving to another city without telling Viera where, but leaving a goodbye letter. Viera’s sadness makes her mother realize how serious Viera’s love is for Judy. While in an anonymous city, Judy succeeds in his struggle to paint, and becomes well known as an artist. Viera, who is now a university student, finds out Judy’s whereabouts. They are reunited through letters, but Judy does not have confidence in Viera’s family. When Judy’s letters stop, Viera goes to the city to find him. It turns out that a disease has led to one of Judy’s legs being amputated, and he is not certain that Viera can accept his condition. When Viera finally meets Judy, she says that she loves Judy and not his legs. H

Sets: The characters meet at home and at school, while just walking around. It is not really clear how to they get to and from destinations like the park, beach or the cinema. Urban scenery is quite limited. The home interiors show the urban style of modern design, but there is only a glimpse of the exteriors from the city, except for a corner of an empty street in the night at the housing complex.

Story-enablers: Viera always wants a good life, including for Judy, while Judy is the person of doubt. After getting the news from Viera about her mother’s opinion about him, he fails in his economics study. The way this affects the relationship makes the narrative flow.

Theme-markers: Judy overcomes his psychological problem and is successful as an artist. The news of the success comes to Viera, and Judy’s letters after that keep on coming, until one day they stop which makes Viera really curious.

Emotional-foci: Judy thinks that his life is finished when the accident makes him disabled, but Viera says that it is Judy that she loves, and not his leg.

Signification: As the plot begins for characters in the last year of high school and the first year of higher education, not a single car is shown. Perhaps this is because they still do not have any income and their parents are not rich; secondly, regarding the historical circumstances of the time that every citizen of the state still needed a formal letter of good behavior. This was the time when the country was at the bottom of an economic condition, just liberated from the Old Order regime, (as the New Order regime named it), struggling to find legitimation by constructing everything.. All these positions are shown in this title. The New Order is a political child that is trying hard to mature. Meanwhile the classic stereotypes, such as Viera’s mother definition of an ideal son-in-law, are still present. The comic-book has become the site of everything possible to signify.

10. Aku Dapat Hidup Tanpa Kau (I Can Live Without You) (62/1967)

Ardian, who really likes singing, is going steady with Netty, but only until Netty reveals the fact that she is already engaged to a student. Netty says it is too long for her to wait for Ardian to finish his study, which is also her mother’s opinion. Ardian is only interested in his hobby. However, Netty’s planned marriage is marred by an incident when a woman claims to be her fiancé’s wife. Hearing the news, Ardian is still broken hearted. In, Medan he wanders around before drifting to Jakarta. It appears that his luck is in show business as a singer, but again another relationship fails for the same reason, namely that he is not an academic degree holder. Then one day Ardian and Netty coincidentally meet. Netty says she is so sorry for Dian. Still feeling wounded, defiantly Ardian continues his singing carrier, to prove that he can live without Netty. UH

Sets: The same architectural type for the houses, exterior or interior, namely the Jengki architecture that was the modern Indonesian architecture of the time. In all it is a modern image.

Story-enablers: The requirement of an academic degree seems like the cause of the broken relationships, but the choice of singing and not going to university is another reason, as the other side of a coin. Tension comes from the conflict between the social and the personal that could break the love relationship.

Theme-markers: When Netty meets Ardian again, she is already married, so the problem is not whether they will reunited or not, but if Ardian can forgive Netty. It turns out that he says thank you. Netty feels uneasy, and Ardian feels right that he could show that he can live without Netty.

Emotional-foci: The second girlfriend, Ratna, also asks about the continuation of Ardian’s study. This escalates the tension, as though the world is now against Ardian.

Signification: The idealistic way of life of stepping out on one’s own path is challenged by the realistic urban ideals, that to survive one should walk the path of the high standard requirement of the dominant hegemonic group in society, that even love cannot overwhelm.

11. Tangis dan Bayangan (Weeping and Shadows) (63/1967)

In a dark alley, Ita and Irwan confess their love for each other, but Irwan says he is only a parasite in Ita’s family. He really worried that this will be an obstacle in their relationship. Irwan is all alone in the world, but Tono, Ita’s brother, brings him to stay with their family. Even though Tono and Irwan are in the same classroom, it appears as though Irwan is from a lower class. When the family finds out the relationship, Ita’s mother says that Ita cannot marry Irwan, because Irwan’s origin is not clear enough. In this situation, Irwan leaves the house and his study, and finds low-paid work that does not meet the costs of living. Ita finds him in hospital with a sickness caused by poverty. When finally Ita’s mother blesses the relationship, Irwan has already passed away. UH

Sets: The dark alley appears twice to reflect Irwan’s kind of space, in contrast to the house of Ita’s family where he seems like he does not belong. The modern interior of the house is never the set for Irwan’s action, except when he expresses his intention to leave to Tono.

Story-enablers: The flashback is Irwan’s past, so the background contrast, and then the conflict become clear. Also the scenes of Irwan’s difficult relationship with Yati, the cause of his somberness, help characterize Irwan.

Theme-markers: This point comes when Ita’s mother says that Irwan is not the kind of husband for Ita. This leads to the fact that Irwan’s fighting spirit is quite low, the opposite of Ita who never surrenders.

Emotional-foci: When Ita meets Irwan at the hospital there is hope for the relationship, then escalated by the successful struggle of Tono to convince his mother that the couple’s relationship deserves support. The news brought by Ita from the hospital makes the tension so high that it causes the anticlimax to be powerful.

Signification: In this title, there is the idea of love challenged by social standards, with the ideological win at the end even without result because the main actor dies. The tragedy can be used as a tool to criticize social standards.

12. Hadiah Ulang Tahun Buat Linda (A Birthday Present for Linda) (64/1967)

The story starts with a conversation between Sjamsu and Victor while Sjamsu is driving a car, about Linda, Sjamsu’s daughter, needing a mother. While they talk, a woman crosses the street in front of them, and she is hit by the car. She does not seem to be in a serious condition, so they bring the unconscious woman in the back of the car to the hospital. Then there is a flashback from the continuous conversation: Sjamsu met Irma, a pianist who works in an amusement building, and they married. Sjamsu asked Irma to quit her work as a pianist. They were happy and even happier when Linda was born. A problem came when the company where Sjamsu worked went bankrupt. While Sjamsu was still looking for another position, Irma went back to her former work as a night entertainer, without Sjamsu’s agreement.. Surprised and suspicious when Irma came home late at night accompanied by the committee of the show, Irma and Sjamsu have a fight that results in the disappearance of Irma in the morning. Irma leaves a letter with the message that she has left to cool down the situation, and asks Sjamsu to take care of Linda. Fortunately, Sjamsu survived the financial problem, working for another company, but he tells Linda a lie that her mother has died. It turns out that the woman hit by the car is Irma. After a while Irma and Sjamsu can make peace with their situation. So to introduce Irma again to Linda becomes a special struggle. H

Sets: There are complete angles of modern architecture for the houses, which from outside is the Jengki style, while the interiors are like the Retro style. This image of modernization is like a break with the colonial or even feudal legacy as a sign of the times. The outdoor scenery looks typically urban, but there are no crowds after Irma is hit by the car.

Story-enablers: The early flash back is like a re-start that gives the perspective to the story, that makes the reunion of Irma and Linda interesting.

Theme-markers: Irma meets Linda as Aunt Irma. While Irma desperately wants Sjamsu to reveal her real status as Linda’s mother, Sjamsu always delays it as he thinks it is too soon.

Emotional-foci: When Sjamsu informs Linda that Irma is her mother, Linda cannot accept it. She thinks it is only a fiction so that Sjamsu can make Irma her step mother. Linda even says she hate Irma for this. At Linda’s birthday, with Victor’s trick as a painter who wants to depict her mother as a birthday present, namely the picture of Irma, Linda finally believes who Irma really is. The tension rises twice, by negative result first, then positive.

Signification: The conflict that constructs the drama originates from the fact that Sjamsu cannot accept Irma’s profession as a night entertainer or as a woman who has her own career. Independently or together, women’s activity outside the house are part of the signs of a mature urban culture. It means this title shows the signs of the early stages of this process. The theme of the plot is not always parallel with the physical signs of the sets, that are convincing as an urban space. It is not clear whether all the pictures reflect the present Jakarta, or are more like an imagination of what Jakarta should be.

13. Aku Bukan Untukmu (I’m Not for You) (64/1967)

Ida has already broken the rules of the dormitory for midwives three times, after returning late after going out with Daud. So after two warnings, the third time makes the matron tell her to leave, while she still had to finish her contract with the hospital. At the same time Daud, who is an engineer, has to go to Kalimantan to work on the dam project in Mahakam. When Daud comes to the dormitory, Ida has already moved to a cheap hotel. To solve their situation, Daud asks Ida, who is all alone in the world, to stay with his mother, a widow, in the village. He will send a telegram, asking his mother to pick up Ida at a restaurant, because he is in a hurry. When Ida comes and waits, she reads in the newspaper, that an accident in Mahakam project has killed Daud. At that moment, Daud’s mother enters the restaurant and sees Ida with tousled hair and tears flowing down her cheek, and she does not get a good impression. In that confusing moment Ida decides not to let Daud’s mother know the news. So they part. In the following days, the difficulty of finding a proper job forces Ida to take the call-girl job. It turns out that the news is wrong and Daud is still alive. Fortunately they meet again and Daud takes Ida to his village, where once again Ida meets Daud’s mother, who now has a better impression of Ida. However, Ida feels guilty that her profession is like a betrayal to Daud. After confessing everything to Daud’s mother, she leaves the house and kills herself, even after hearing from his mother that Daud still wants to marry her. But Daud only finds Ida’s body on the street, having run before a speeding car. UH

Sets: The surroundings of the story is like a perfect Jakarta, where there are no slums or even becak (pedicabs), and even the cheap hotel seems without any employees or guests other than Ida. The place where Ida circulates as a call-girl does not show the actual wrong work of the profession, only the high-class style of the urban culture as an imagination. The houses and restaurants, as always, are represented with perfect design, even Daud’s house in the village, which is mentioned as built intentionally as modern architecture.

Story-enablers: The news that Daud has died in the accident makes way to other directions, so when the story lines at the end are reunited, for Ida many things have already gone too far. The story form constitutes another direction as a new start.

Theme-markers: The tensions already start when Ida is expelled from the dormitory, but the real tension appears as Ida parts with Daud’s mother, when there were high expectations before.

Emotional-foci: Ida thinks that she herself has already betrayed the sacred love, and nothing could cure this. But Daud does not mind at all.

Signification: Ida’s realism in thinking that she should take any job available, challenges her as she believes her work as a call-girl is sinful, which also means a betrayal to her love with Daud. The urban environment has not liberated her enough, while it works for Daud, who seems never disoriented with anything in the struggle of values. He can accept Ida’s situation. The urban setting, in confrontation with the village, is portrayed as having the potential to make someone confused, and that is the time to find peace of mind in the village, where the urban people come from, even with an idea of a modern house that they bring from the city.

14. Melodi di Achir Tahun ( End of Year Melody) (64/1967)

Darta is a student who comes from a poor family, so he has to give piano lessons.. His girlfriend is Wida, a singer with a better background and better income, and this makes Darta sensitive, besides he cannot stand watching Wida’s fans around her. On the other hand there is a new piano pupil, Ira,who is falling in love with Darta, who tries to ignore her because of her age. However, after Wida decides to marry another man, because of Darta’s constant self doubt, Ira appears as a mature woman after coming of age. H

Sets: The urban city appears as an environment for the professions of singer, student who also gives piano lessons, and the people around them. There are exteriors of the business district with luxurious cars, the interior of a singing hall, and interiors of houses in the modern style. Darta’s room as a student is also part of these interiors.

Story-enablers: Tension escalates when Darta sees Wida surrounded by fans, something common for a popular singer. Darta compares himself to Wida’s world in a miserable way.

Theme-markers: Ira decides to take distance from Darta, but before she leaves, she finds her name in Darta’s diary that was left behind in her house. What is written there make her happy.

Emotional-foci: Darta shows Wida’s invitation to her wedding party, which means there is no competitor to win Darta’s heart.

Signification: It is always about social differences as obstacles to relationships, in this case the difference of wealth, and also the community, which should not happen in the spirit of urban culture. So while the surroundings seem completely modern, this is not true of the attitude of the characters, for example Darta’s rejection of Wida’s offer, only because Wida is a woman. That is the stage of the urban condition in a process.

15. Sebuah Noda Hitam (The Black Stain) (319/1968)