A Dark and Bittersweet of Coffee in Colonial Land of Java XVIII-XX CE

Oleh Ary Budiyanto

…. Kubuktikan kebenaran ratusan bulan kuseduh kopi plastikan hingga kopi luwak harum kotoran terasa apa yang Bapak resahkan kenapa ku tak boleh minum kopi karena di cangkir ada air mata kopi…

Serang, 20 Maret 2008 (Gong, 2014, p. 2)

Sufi, Hajji, and Coffee in Nusantara: A Trans-Cultural Diffusion

Early in history, this exotic coffee drink was introduced by the Arabs (Yemen) and this coffee ore began trading in the 16th century during the Ottoman period. This coffee plant may have long been cultivated in Ethiopia and spread to Yemen in the mid-sixth century CE estimated at the time of the Abyssinian invasion to the South of Arabia. Al-Mukha port was one of the busiest ones in Yemen in the 15th century CE mainly thanks to the coffee commodity. From here the name of Mocha became the legendary and iconic brand of this new beverage known as Mocha-coffee (Tagliacozzo, 2013, p. 46). This coffee in the Islamic world in the time of Abassyiah (ca.10 CE ) was originally better known as a drug called Bunk, which is “a hand-cleansing compound containing roasted and crushed coffee beans and husk” (Nasrallah, 2007, ft.54, p. 506).The coffee beans that have been roasted until dark-brown was usually just chewed away. Furthermore Nasrallah, the translator of Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens: Ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq’s Tenth-Century Baghdadī Cookbook, gave an interesting note on his Glossarium that initially the qahwa drink (coffee mixed with spices, some of its from the archipelago like cinnamon, ginger, and cloves) was probably known only locally and limited to a community until the mid-15th century CE (Nasrallah, 2007, pp.

768–767). However, the testimony of Chau Ju-Kua’s (1170-1231) travel notes about the habits of the Ta-Shi (the Arab) enjoyed this ‘wine’, so this drink was very popular in the society of that era and he called it “Méi sī dǎ huá jiǔ (眉 思 打 華 酒) which is very heating and stimulating” (Rukuo, 1965, pp. 115–116). Although called jiǔ does not mean it is liquor because it is clearly forbidden in Islam, Méi sí dǎ huá perhaps was a corrupt spelling of two words al-maysam and qahwa (الميسم القحوة) (Nasrallah, 2007, p. 768) in the ears of Chau Ju-Kua. But Nasrullah noted that this qahwa beverage may have been well known around Damascus in the early 6th century CE , as recorded from Uday bin Zayd’s journey during the era of Khosrou (d. 579 CE ) in Damascus commenting on the wine drink served (al-syamul) was none other than a black bitter qahwa [etymologically: dark and dim] beverage (Kaye, 1986; Nasrallah, 2007, p. 769).

Besides the mythology of Khaldi the legendary herder or Jibril who brought the coffee drink to the Prophet, the historical narratives by Ukers (1935, pp. 7–19), Hattox (1985, pp. 12–26), and Seidel (2000) showed that it was the 13 century sect of Sufi Order, the Shadiliya, who introduced this culture of drinking Qahwa. Later there was the Bekhtasi Sufi order which became the legendary saint patron of coffee-houses in Ottoman, ultimately in Istanbul (Sajdi, 2014, pp. 117–132). Istanbul and Ottoman were popularly known in Jawi texts as Nagari Rum. Even in the Mughal Kingdom of India coffee has become a trade commodity and special enjoyment of the palace, this was recorded during the time of Khurram (Shah-Jahan-i-Azamn, r.1627-1658) whose trading period included coffee and his son, Aurangzeb (Alamgir I, r.1658-1707) who really likes to drink this black infusion (Faruqui, 2012, pp. 100, 117).

The earliest note of the presence of this dark and bitter beverage in Southeast Asia (which may be their coffee powder also mixed with spices, ala Arabic) was the testimony of La Loubère. La Loubère conducting the envoys in Siam in the years of 1687-1688. He noted that “the Moors of Siam drink coffee, and the Portuguese do drink chocolate, which comes to them from Manille, the chief of the Phillipines, where it is brought from the Spanish West-Indies.” And they, the Moors of Siam also enjoy the Arabic-Shisha/Hookah (La Loubère, 1693, pp. 23, 180).” Although we do not know whether the Moors were genuinely Arabs or not, at least these notes reinforce the sketch drawings of Romeyn de Hooghe showing a variety of drinks, including coffee, tea, and chocolate, in Bantam (Banten, Java) in the same decade. Special sketch was depicting in detail how to prepare coffee for a beverage. The images of people in cloaked and worn turbans were probably Arabs in Batam (Banten), although Javanese Muslims at that time also accustomed in wearing Ottoman-style outfits. Tagliacozzo (2013, p. 47), based on the study of Brouwer (1997), also notes that along with the hajj and spices trade relationships in 1614-1640, coffee beans have become promising commodities in Arab-Ottoman ports, notably al-Mukha (Mocha) Yemen. A time when the Egyptian ‘conglomerate’ Ismail Abu Taqiyya (1580-1625) made an immense wealth as coffee and sugar trader. Abu Taqiyya perhaps one of the leading pioneer on this popular consumption of the coffee and sugar commodity and introduced to the European merchants and market through Vienna (Hanna, 1998). So, no wonder if de Hooghe and La Loubère, on duty to reported and recorded this prospective business trend I 17 centtury for their authority respectively. Brouwer also noted that there was a connection of Mocha with ports in Southeast Asia such as Achin (Aceh), Priaman and Batavia in 17th Century.

Left & Middle. Dranken in Oost-Indië; BI-1972-1043-21 Right. Market and trade in Bantam; BI-1972-1043-8. From Album met voorstellingen van planten, dieren en volkeren van West- en Oost-Indië, Romeyn de Hooghe, 1682 – 1733 https://www.rijksmuseum.nl accessed 2019-10-02 19:39:52

From the meticulous description of Tagliacozzo in his book The Longest Journey: Southeast Asians and the Pilgrimage to Mecca (2013) and H. Chambert-Loir, Naik Haji di Masa Silam (2013), it appears that the relationship of Muslim of Nusantara has been established for at least since the 15 century, the time when the coffee or qahwa became popular. The spread of Islam to Indonesia is not only done by ordinary pilgrims, or hajj followers of the tarekat or Sufi, but also the role of the network of Hadhrami traders and scholars of Yemen (Azra, 2013; Ho, 2006). As noted by Van Bruinessen (1998; see also Azra, 2013), that the teachings of the Shadiliya congregation have long been present in the scholarly treasures of the archipelago albeit in an eclectic form with other tarekat teachings. What is interesting is the information from Tagliacozzo that two early Bugis manuscripts found from Sulawesi in the Indies discuss the teachings of Hajji Bektashi in the British Library Manuscripts Collection (both Add. 12358, F: ff. 21r.–27v.; and Add. 12365, C: ff. 10r–17r). “Hajji Bektashi was the chief artillerist (or gunnery specialist) of Istanbul, who was the founder of the Bektashi order and the spiritual source of inspiration for the corps of Janissaries in the Otoman Empire,” Tagliacozzo noted (2013, p. 33). He was the legendary saint patron of coffee-houses in Ottoman (Sajdi, 2014, p. 126). It appeared that this exotic drink (coffee, tea, and cocoa) has been popular in several bustling ports of international trade in the archipelago, at least in the middle of the 17th century. It is not surprising that traders tried to make these commodities more profitable in the international market, especially in Europe which at that time coffee was the promising market, as Turks coffeehouses life-styles captivated European’s taste. Coffeehouses began to bustle and sprung up to rival the previous drinking stalls, Bars and Taverns. This create a sophisticated culture of café since 1640’s in Venice, 1650’s in London, 1660’s in Paris and The Hague, and many others European and American cities in 1700’s (Ukers, 1935). Since then, coffehouse or café lifestyle was a place for local elites rendezvous.

Habermas notes that between 1680-1730 was the “golden age of the coffeehouses” and as in the Islamic world under the Ottomans at that time these coffeehouses became a place for people to gather, waste time, discuss, hold works of art and literature, talk about religion, and criticize the situation social economy, and politics. It became a gathering place for new middle class elites, traders, thinkers, artists, writers, even ordinary people (Allhoff, 2011, p. 90). Coffehouses is identical as a hangout for the patriarchal world of that era. However, in Constantinople, women often enjoyed the same gatherings and conversations accompanied by the same coffee in public bathhouses. In Constantinople itself, by 1650 there were more than 600 coffeehouses (Hansen & Curtis, 2008, p. 497). Since the coffeehouse was opened in England in 1652, then Paris in the 1670s this new lifestyle then spread throughout Europe. The ruling and religious authorities of the time were nervous about this new cozy gathering place, because it was not uncommon from this gathering the radical and subversive new leaflets and debate of ideas quickly spread (Ellis, 2011).

In the Islamic world the events of attempted closure of coffeehouses and the prohibition of the circulation of this coffee had begun during the Mamluk Dynasty by the government and religious authorities of the city of Mecca in 1511. They suspected the Sufi groups who used this bitter and black drink in their spiritual practices. Then in 1623 in the period of Sultan Murad IV of the Ottoman Empire, also issued a ban on coffee and created a new law governing the drink, but to no avail. Then again in the 1670s, the Sultan tried to close down all Constantinople’s coffeehouses, but failed. It is interesting to mention here that the response of Sufi scholars in Java to the permissibility of Islamic law (Fiqh) over the practice of drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes in the Javanese [santri] community at that time, was only seriously addressed in the 1930-40s with the publication and spread of the book of Irsyad al-Ikhwan Fi Syurbati Al-Qahwati wa al-Dukhan, the charismatic cleric from Kediri East Java namely Sheikh Muhammad Ihsan bin Muhammad Dahlan al-Jampasi al-Kadiri al-Jawi al-Jawi asy-Shafi’i (1901-1952). The book specifically discusses the Islamic law of drinking coffee and smoking. It is probable that this was responded to the habit of drinking coffee and smoking kretek in every occasion. It was noted that the kretek cigarette industry at that time was gaining popularity in Javanese society and became the same unsettling conversation at the center of the Islamic world in the early mid-20th century in Java (Badil, 2011; Hanusz, 2000). In the same spirit that is facing the insistence on the discourse about the law of smoking and drinking coffee, this book was even re-published under two different titles: Kitab kopi dan rokok: untuk para pecandu rokok dan penikmat kopi berat (Daḥlān, 2009) and Kopi & Rokok dalam Perbincangan Ulama (Jampes, 2019).

In Europe the same thing happened, but all of these coffeehouse closure efforts were never successful. In Italy in the early 17th century, many religious leaders requested that the drink be banned and considered a demon drink. But conditions changed when Pope Clement VIII tasted coffee and declared that the drink was delicious and even considered a blessed drink (Pendergrast, 2010, p. 51). A stiff resistance to the existence of coffee shops in London was the 1674 Women’s Petition, which protested against men in coffee shops who wasted a lot of time, while women were forbidden to visit coffee houses, unlike in France. Then, on December 29, 1675 the English King Charles II issued a statement about the Prohibition of Coffee Houses, with the excuse of making people ignore social responsibility and disturb the stability of the kingdom. Protesting voices also appeared in London. The climax, two days before the rule took effect, the king resigned. The prohibition of coffee in Sweden was in the range of 1746. At that time coffee was a prohibited drink and was considered to be similar to poison. In 1777, King Frederick of Prussia made a manifesto stating the superiority of beer over coffee. Coffee was banned because it killed the beer market and high demand for imported coffee threatened the domestic economy (Pendergrast, 2010, p. 58).

Although there were many restrictions on the enjoyment of coffee by the authorities and the clergy, the coffee trade in the 17th century was highly in demand and obviously very profitable. In trading ports coffee and other commodities were located, the Arabs and Africans trader authority prohibit the sale of fresh coffee ores. It said that coffee ores that will be sold outside must be boasted and dried and peeled beforehand or even the seeds have been broken down so they cannot be planted. All of this was to monopolize the trade of coffee commodities. Until Hajj Baba Buldan arrived, a Sufi follower from Malabar who was able to smuggle and plant the seven seeds of this commodities in India where he came from. Baba Buldan was probably not the only one who wanted to profit from commodities that were increasingly in demand in Arabia and Europe, until then the Dutch took control of the coffee plantations planted by the Arabs in Sri Lanka (Ceylon) and developed them in Java, after seeds from ‘Baba Buldan’ were less successful breeding (Indarto, 2013).

Over the next few decades later the VOC started looking for ways to get involved in this potential market and in 1696 the VOC introduced the seeds of the arabica beans from Ceylon. In short, the seeds of this plant then for the first time were brought to Batavia and planted. However, this initial attempt failed because of floods, until in 1699 the coffee was successfully planted in Batavia and partly in Sundanese then spread widely throughout the Dutch East Indies (Indarto, 2013; Ukers, 1935). In 1711 the results of coffee from Java successfully entered the European market for the first time in Amsterdam. It may be that the Dutch was not the only ones who are trying to breed and grow coffee outside of Arabia such as India and Ceylon, but the success of their experiments in cultivating coffee on Java accelerated the spread of this coffee plant. In Sumatra, Minangkabau, for example Arabica coffee has been found cultivated since the late 18th century and became one of the economic commodities that aroused the Islamic economy in the Malay world in the 19th century (Dobbin, 2016). In 1725-1780 Dutch East Indies became the largest coffee plantation after Arab and Ethiopia. Indeed, since the 18th century it began to be known as Mocha-Java Coffee. Indeed VOC and later Dutch Government never monopolized this commodity but all of this East Indies harvest, by enforcement law and free labour, were for the global export not for local consumption (Breman, 2015; Bulbeck et al., 1998, p. 10). And, it was since 1893 in World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, when the Java Village booth was served a cup of coffee in its restaurant free for all the guesses that it was known as A Cup of Java (Teggia & Hanusz, 2003). Even though, American knew the term Java Coffee ealier around 1860s through Osborn’s Celebrated Prepared Java Coffee, the pioneer ground-coffee package, which is put on the New York market by Lewis A. Osborn (Ukers, 1935, p. 435) but not very resonant.

There is an interesting account of “Early Dutch Trade and Yemen” by Daniel Martin Varisco (2000, pp. 58–61) who reviewed the writings of C. G. Brouwer, Dutch-Yemeni Encounters: Activities of the United East India Company (VOC) in South Arabian Waters since 1614 (1999). Brouwer pointed out that the most profitable VOC commodity trading reality from the beginning was from coffee, this is a femporal information that is not like much heard in history lessons in Indonesia. Brouwer showed us what types of VOC merchandise were transported from the Dutch East Indies: pepper, cloves, nutmeg, mace, benzoin, sandalwood, camphor, lead, lead, sugar, Chinese clothing, etc. to be sold to the Arab market through the port of al-Mukhâ and surrounding areas. It is not surprising, in fact, that many of the commodity goods brought by the VOC were devoid of interest because what was sold were similar items carried by old traders in the sea silk route. Only certain spices and porcelain (for the porcelain business see Volker, 1954) were quite promising. In reality, pepper from Sumatra and cloth from India are not at all desirable and are often at a loss. “In fact, cauwa or ‘coffee’ was the sole product which was shipped more systematically and in larger quantities; sold in Basra and Gamron (Bandar ‘Abbâs), this product yielded some additional cash.” Towards the end of the 17th century the coffee market in Europe increased and the VOC could only initially buy from Indian traders in the ports of Surat and Malabar. Entering the 18th century, in 1706, the VOC became more serious in this coffee trade for the European market since the arrival of Johan Ketelaer with his two offices in al-Mukhâ and Bayt al-Fakîh. In the following years, this caused the price of coffee to continue to rise due to fierce competition between purchasing agents Turkey, Britain, France, Belgium and the Netherlands, and its supply was running low. This is why the VOC in Java began to expand the wider coffee field for market needs, while the coffee auction in Europe was still declining. And coffee production in Java was able to surpass production in al-Mukhâ, fierce trade competition and systematic promotion made Javanese coffee begin to get priority in the European market. The term Mocha-Java Coffee becomes Java Coffee. At this point it becomes clear the reason behind why Max Havelaar (Multatuli, 1972) was concerned about coffee and its auctions rather than other infamous colonial commodities, the spices. But the abused policies and rules of iron fist by the local rulers and their’s colonial comrades, in operating this free-labor and forced cultivation, added the various tax articles have left the lower-class Javanese in extreme misery (Fasseur, 1991).

Problem statement, research questions and objectives

It has been mentioned above that the trade relations in the archipelago with the Islamic world have changed the culture and religiosity of the archipelago. The long journey of the “al-jawiyin” pilgrims from the “land below the wind” countries to the Islamic center brought back what was obtained to the archipelago, one of which was the pleasure of sipping this coffee. So it is not surprising to say that coffee spreads with Islam and Islam spreads the fragrance and the pleasure of sipping coffee brew. The Sufis called the drink that anesthetized the devotion of worship as “the wine of Islam” (Seidel, 2000). In the Islamic world the development of coffee houses, how to brew, how to roast, how to pound, how to mix with spices, to how to present with various tools and luxurius coffee-sets, has led to the emergence of a new professional and specialization of working world, a fragrant and aromatique world of café culture. A culture that celebrates coffee drinks elegantly (Mlandu, 2017). A glimpse of the history above, noted the role of these coffeehouses became the driving force of social, economic, artistic and cultural change to the practical politics in which these coffee houses are located; as in the Arab world, Europe from the early centuries of their introduction to coffeehouses and even to China in the 1920-1930s (Ellis, 2011; Hanna, 2003; Melton, 2001; Pang, 2006).

But it becomes a problem when in Java in particular, and the archipelago in general, there is no trace of its historical record that they have a sophisticated consumption culture development in enjoying this bitter and dark potions. Even though this region in the Dutch era was the biggest coffee producer after Arabic, history records that many Javanese had become pilgrims centuries ago and were active in the Sufi order network, which was so close to the world of coffee (Azra, 2013; Othman, 2003; Tagliacozzo, 2009, 2013). A testimony to the role of Sufism / tarekat which became an agent of the distribution of the tradition of drinking coffee in Javanese is the account of Carl Peter Thunberg’s testimony in 1772-1775 in Lankan (Ceylon, Sri Lanka) where there was a group of people reading a book in communal recollection (Dhikr Ratieb) in a group of tarekat attended by Javanese. And one of the Javanese was a figure of a prince named Raden Mas Kreti who joined his father exiled to Lanka in 1728. Thunberg noted: “Between singing and reading, coffee was served up in cups …” (Laffan, 2013, pp. 217–218). But, it was in Lankan what about Java? As there was no written evidence on this practice. What in common to drink in ratieb, maulud, or khatam al quran congregation in Java and Nusantara as far as I know the popular drink to accompany this activity was and is known sherbet. It is not clear whether coffee was one of the ingredients. What is certain is that Centhini mentioned the “serbat coffee” drink. Nevertheless, it should be noted that in Javanese metrum of prose (macapat) there is no coma in its sentence, so it could be read ‘serbat, coffee’ instead of ‘serbat-coffee’.

Further, Matsuyama and Anthony Reid noted that these coffee drinks were only popular in the 18th century after the Dutch began cultivating in Java since the 1690s (Matsuyama, 2003, pp. 270–271; Reid, 1992, p. 45). The question becomes, was there really a culture of drinking coffee in Java and to what extent was the influence of the Arab coffee drinking styles? Was it true that there was no socio-cultural and political movement sprung from the coffee shops in Java as in the Arab and Europe, why? To answer some of the questions that arise is the objective of this preliminary research paper.

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework

A book about coffee in Indonesia is only just beginning to bloom before the 2000s. In my opinion, the most comprehensive history of the origin of coffee in Indonesia is the book by Prawoto Indarto, The Road to Java Coffee (Indarto, 2013). While the short and light version of the history book from coffee in Indonesia is the work of Arvian (2018) KOPI: Aroma, Rasa, Cerita. Meanwhile, the unique world of coffee in Javanese culture was interestingly discussed by Teggia & Hanusz in his book A Cup of Java (2003). The history of coffee in colonial life of Java are competently two of Jan Breman’s works, Mobilizing Labor for the Global Coffee Market: Profits from an Unfree Work Regime in Colonial Java (Breman, 2015) and Keuntungan Kolonial dari Kerja Paksa: Sistem Priangan dari Tanam Paksa Kopi di Jawa 1720-1870 (Breman, 2014) which discusses the history of the Dutch colonial economy and political policy in coffee plantations and the mobilizing of its forced laborers to gain maximum profits. There is no historical writing about café culture or the tradition of drinking coffee in Java. There are two interesting writings about the tradition of drinking coffee in contemporary Java, namely the thesis of Lestari, Sejarah Warung Kopi Blandongan (Sebuah Studi Tentang Perkembangan Warung Kopi Blandongan (Lestari, 2009), 2009) and Rosa’s article “Kopi Tiga Dimensi: Praktik Tubuh, Ritual/Festival dan Inovasi Kopi Using” (Rosa, 2016) but both were in the perspective of cultural studies, not purely history. Recently there was an interesting book about the social history of Aceh’s coffee, entitled Hikayat Negeri Kopi (Syukri, 2016).

As written by Marino & Crocco (2015) who saw Pizza as a historical artifact, various studies on the existing coffeehouse or café culture are efforts to depict the history of the commodities that bewitch the world. There have been many studies of the history of coffeehouses conducted, to mention a few, which are The Viennese Café and Fin-de-Siècle Culture (Ashby, Gronberg, & Shaw-Miller, 2013); The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse (Cowan, 2005); The Coffee-House: A Cultural History (Ellis, 2011); Coffee and Coffeehouses the Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East (Hattox, 1985); The Rise of the Public in Enlightenment Europe (Melton, 2001); Ottoman Tulips, Ottoman Coffee: Leisure and Lifestyle in the Eighteenth Century (Sajdi, 2014); and The Vienna Coffeehouse Wits, 1890-1938 (Segel, 1993). All of these writings give an idea of how rich the cultural results of a drinking habit in nations that have been fond of drinking coffee for centuries. Indonesia, especially Java, which became a part of the world history of coffee, at least after entering the 18th century, should also develop the culture of this coffee drinking habit.

From the writings about the coffee shop above, it appears that the introduction and spread of Ottoman cafe culture to the world (Europe) has been adapted and acculturated with the local culture according to the tastes of the people. In the place where the coffee was and is brewed, magically, it creates an unique socio-cultural atmosphere through its fragrance. A long encounter from the 16th century onwards, by sea and land, made coffee a part of the world. But, comparing the image of café culture in coffeehouses in the world, the miraculous beauty of brewing and enjoying coffee, apparently, did not happen in Indonesia. My light ethnographic research in Malang in 2017, showed its archaic tradition of preparing a cup of coffee in its simplicity. There is no wow lifestyle, and even tends to be stereotyped as a taste of plebeian drinks. There are no unique ‘ritual’ for enjoying coffee like in Arabia, Turkey, or in European countries other than as entertaining guest or an ordinary daily drink. Until in the 2000s I witnessed a new culture of drinking ala Starbuck coffee. Since then, modern European café culture has captivated Indonesian young generation. As a theoretical framework this cultural diffusion will see the historical roots of Javanese café culture. To reveal the main quest of this article: Were there any situations that made coffee drinking culture in Java, in particular, did not develop likewise in the Arab world?

Rachel Laudan’s article entitled “Homegrown Cuisines or Naturalized Cuisines? The History of Food in Hawaii and Hawaii’s Place in Food History discusses the history of the emergence of Hawaiian “local food” which actually originates from the adaptation process of three main cultures (European, Asian, and Native Hawaiian). It is this encounter of three tastes that has led to the innovation of what is now called their local specialty food. As with the creation of local Hawaiian food, it will be seen the extent to which the process of adaptation of the culture of drinking coffee in Java takes place and manifests in its simplicity. Ormrod argued that “Adaptation theory, on the other hand, provides a means of explaining both acceptance and nonacceptance. The need to be adapted -an important need for the potential adopter as well as the diffusing innovation- and the processes through which adaptation is achieved provide a basis for understanding both human motivation and action, and thus clarify the responses that occur, or are likely to occur, when an innovation arrives at a new location. They also clarify the experience and ultimate fate of the innovation at that location (Ormrod, 1992, p. 262).” From the theory of adaptation in cultural diffusion (Ormrod, 1992; socl120, 2013) this paper will look at historically what kind of adaptation accepted and rejected by the Javanese in enjoying this bitter coffee brew, hence that sophisticated café culture did not emerge in Java.

Methodology

This study was originally based on our ethnographic research about coffee drinking culture in Malang during July-October, 2017 by interviewing and observing some of the old and legendary coffee stalls in Malang. The results were then questioned it by tracking the history of Javanese coffee drinking culture from old Javanese archives such as Serat Chentini, Kedjawen Magazine and other primary and secondary sources, which were then strengthened by visual analysis of photographs of colonial coffee vendors. Analysis of this archival and ethnographic data was then written as a historiography of drinking coffee culture in Malang as a representative of Java café culture in general. I will present in this paper in two prelimanary discussion in answering the research questions. In Result (analysis and findings) section, First part started with the ‘ethnographic’ view on how the Javanese enjoyed their coffee and what was their ‘coffeehouse’ looklike. Second part discussing the internal and external ‘situation’ that made qahwa and its café-house, the Islamic signature beverage of coffee, ‘underdeveloped’ in Java. Third part is conclusion.

Javanese Style of Enjoying Coffee in Centhini and Others

Looking for traces of Javanese coffee drinking lifestyle in the past in old literature, there is nothing to be referred to other than Serat Centhini. This literature was originally titled Serat Suluk Tambangraras and written in 1814 – 1823 by the initiative of KGPA Anom Amengkunagoro III son of Pakubuwono IV, king of Surakarta (1788-1820). The two main supervisors of this “Javanese Encyclopedia” were Kyai Kasan Besari, Ulama Agung of Panaraga and Kyai Mohammad, Ulama Agung of Kraton Surakarta. Serat Centhini is a story of the reality of the life of the early Javanese people of the early 19th century, although it is wrapped in fiction in the Javanese macapat. This book also gives an overview of the food and drinks that existed in Javanese society at that time when the Colonial government had introduced more than a century of new commodity products such as coffee, tea and chocolate. To facilitate the exploration of culinary footprints in Centhini, I use the guidebook entitled Kuliner Jawa dalam Serat Centhini (Sunjata et al., 2014) and interesting article from Timbul Haryono, “Serat Centhini Sebagai Sumber Informasi Jenis Makanan Tradisional Masa Lampau” (Haryono, 1998).

At first I thought I would find two types of coffee brewing after seeing there are two terms in the mention of this drink in Centhini, namely kahwa (ar. Qahwa) and coffee (dutch. Koffie). Kahwa in javanese refers to two conotations: to named steeping coffee leaves or the Arabic style of ground coffee mixed with spices; while the term coffee is commonly known as ordinary brewing presentation, the tubruk style, where coarse coffee grounds are boiled along or just directly poured hot water into a glass or a cup where coarse coffee grounds are boiled along or just directly poured hot water into a glass or a cup filled with 1-2 tablespoons of coffee powder. And this style was previously no sugar added. But today Kopi Tubruk is where coarse coffee grounds are boiled along with solid sugar, resulting in a thick drink similar to Turkish coffee. Thus, I found the word kahwa 22 times and the word kopi 39 times scattered in Serat Centhini. However, the word qahwa and coffee in Centhini did not refer to the Arabic and Javanese style of coffee presentation as predicted. This is evident in the following metrum of macapat in Centhini:

121. Gambuh

Sawusira anginum | wedang kahwa Cêbolang umatur | sarêng sampun kasiraman wedang kopi | kang kalimput nulya thukul | nênggih kang dèrèng kacriyos || (Sastrakartika, 1932, p. 130)

Therefore, it was clear that the word kopi and kahwa was identical. It was used merely for the sake of macapat rhyme. It just the same type of serving coffee style. This Centhini’s brewed coffee was also served by filtering (jv. tepas). In Serat Damarwulan (Anonymous, 1810, p. 102) it was also known kopi puwan or peresan (pressed). Meanwhile wedang kopi lan puhan or coffee with milk was also mentioned in Centhini (Kamajaya, 1986a, p. 108). But in the santri environtment, Centhini also mentioned the wedang srêbat kopi (Kamajaya, 1986b, p. 68). I am not sure if it was serving coffee with spices just like the Arab, but srebat/serbat in Javanese is always connote as mixed herbs and spices beverage, commonly it used ginger and cinnamon. Wedang kopi also served with sugar palm (gula merah) or rock sugar (gula batu) and kopi luwak (chivets coffee) was also listed in Centhini (Haryono, 1998, pp. 96–97; Kamajaya, 1986c, p. 209). In fact, the Javanese in Centhini also knew coffee-leaf tea or ‘wedang ronning kahwa’ as beverage served with sugar palm or gula kelapa (Kamajaya, 1986d, p. 135, 1989, p. 111) it was when Jayengresmi (one of Centhini main characters) at mount Muria, Kudus. This aia kawa or kopi daun in Sumatranese was mentioned in Max Havelaar (Multatuli, 1972, p. 43; Parintangrintang, 2014). Maurik’s novel witnessed in Tosari, East Java, why Javanese prefer to drink this kopi daun, Maurik told us that “The native, who yields his government coffee, must buy the beans for the coffee that he himself wants to drink, and therefore prefers to take care of an extract of the leaves of the coffee tree, which gives a brown, soggy drink, somewhat the taste of coffee has (Maurik (jr), 1897, p. 373).” In fact, coffee-leaf tea or kuti beverage is common in Ethiopia since memorial time (Novita et al., 2018).

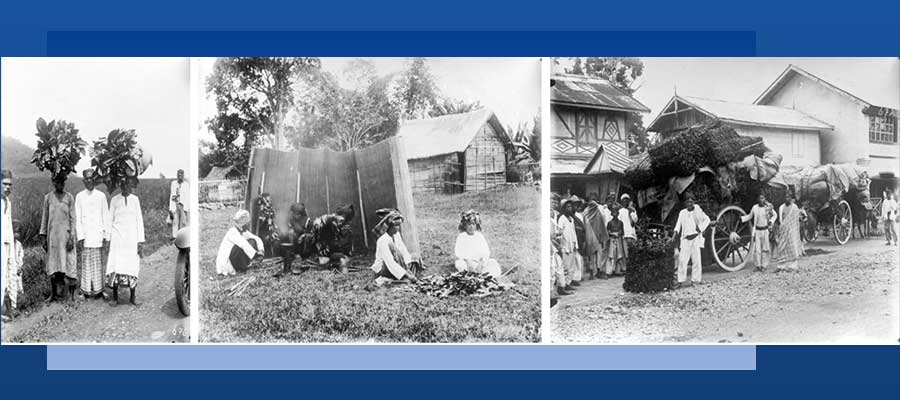

From left to right: Men carry harvested arabica coffee leaves, for the preparation of kopi daoen; women preparation of kopi daoen, the coffee leaves are roasted on a low heat until the leaves have turned brown and dry; The transport of kopi daoen (coffee leaves) to the market at Pajakoemboeh, Sumatra’s West Coast; these photographs witnessed that coffee leaves had its promising market for local people at that time, mostly they collected the leaves from the pruning branches. Collected from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Manufacture_of_coffee_in_Indonesia Accessed 05/10/2019.

Sweet and savory snacks are also known as companion to enjoy coffee in Javanese Centhini, and most of these snacks can still be found in traditional markets. Timbul Haryono has collected the names of these delicacies, to name a few of its: puthu-têgal, carabikang, mêndut, koci, sêmar mêndêm, buntêl dadar, jagung bakar, pohung bakar, uwi lêgi, bêntul, gorengan linjik, katela and etc. (Haryono, 1998, p. 97). It is interesting that the style of respecting guests by offering coffee (or tea) at Centhini accompanied by traditional snacks, until the middle of the early 20th century, remained a marker of low class and poverty of Javanese, compared to those who drank coffee milk, buttered bread with cheese, (often with half-cooked eggs) identified with a high class style, parallel to Europeans (Jv. Londo). Bancak, a fictional character who talks about the style of respecting guests in these different classes of the time, illustrates how a high-class person offered his guest: mau minum apah, anggur, kwas, limun, tèh, kopi? So, what do you want to drink, wine, squash, lemonade, tea or coffee? (Kajawen, 1930, pp. 300–302). A contemporary book by Alamsyah, Kue basah & jajan pasar: warisan kuliner Indonesia (2006) about traditional Javanese snacks can be studied and compared more deeply with a variety of snacks at Centhini which was written in the early 19th century. Dukut Widodo, a senior journalist and popular historian, wrote of his own memoirs on drinking coffee with his father in the 1950’s in Surabaya and Malang, when drinking coffee his father always provides steamed or fried dishes such as bananas, cassava, sweet potatoes or yams, jemblem, getas, lemet, and etc. And of course, coffee (or tea) always accompany after a big meal (Widodo, 2006, p. 389, 2011, pp. 176–183). As is the custom of people drinking coffee in the world, Javanese also like Arabs who offer coffee (or other drinks) as courtesy and hospitality to guests. And the habit of the people in serving coffee was/is to serve it with snacks, smoking cigarettes, and discussing everything.

More than a hundred years after Cethini, it can be seen how Javanese Moms in the Kedjawen / Kajawen magazine published by Balai Pustaka became more familiar with coffee. There were two interesting information about coffee, namely: the writings of Mev. Citrapartaya and Nyi Anim in the ‘Jagading Wanita’ rubric in this magazine. Mev. Citrapartaya noted the existence of various drinks in Javanese such as: tèh, coffee, soklat, tèh mèlêg (milk-tea), milk coffee, soklat coffee, pêrêsan coffee, tigan coffee and etc. and in the past, Mevrouw said, the sugar used for drinking was palm sugar, coconut sugar or cane sugar. According to Mev. Citrapartaya Javanese also know other “coffee-brewed” drinks, for example “coffee” made from “sêkul aking (dried stale rice), woh bendha (artocarpus elasticus seed).” Thanks to a long encounter with various nations, these drinks were created, Mev said. She then shared her special recipe: egg yolk-coffee (Coffee Tigan), its inggredients were eggs, rock sugar, and hot coffee that was brewed specifically with “kothok” technique. The “kothok” technique is to use coffee water that has been cooled overnight with the “tubruk” technique, then brewed again in the morning and filtered before being poured slowly in a glass containing rock sugar and egg-yolk beams until foamy (Mev. Citrapartaya, 1935, pp. 123–124). Like Kopi Talua Minang or Padang (Dongeng Kopi, 2016) and possibly also Cha Pe Trung Vietnam (Setiawati, 2017) this Java tigan coffee was also believed to increase stamina.

Meanwhile, Nyi Anim’s gave tips to the reader how to made the fragrance of coffee grounds can last longer and taste better. She suggested to mix rock sugar for a few moments when the coffee will be finished roasting. By comparison the sugar is a quarter of the total roasted coffee. Or, Nyi Anim said, before roasting it, coffee lovers had to mix small pieces of dry fresh bread into one third of the total roasted coffee. Nyi Anim guarantees that the taste of the coffee will be more savory, not bitter and sour, and the fragrance will last longer even though the coffee box is often opened and closed (Nyi. Anim, 1937, p. 113). Until now the traditional coffee grinders in Malang still mix their coffee with dried corn kernels, or rice, or dried stale rice in the process of roasting, and it is believed that their coffee concoctions are more delicious as well as adding quantity because of expensive coffee beans. Obviously, the coffee beans they bought certainly not the best class quality. Indeed, this traditional ground coffee market is for lower class people. While in Aceh the roasting technique is similar to that of the Chinese peranakan coffee business in Malaysia or Singapore, which uses sugar, butter, egg-yolk, condensed milk, and other secret ingredients (marijuana) to create a distinctive coffee flavor (Suparta, 2019). The secret techniques are done by traditional roaster gatherers, it is believed that the more savory flavors from coffee can come out, but the bitter and sour taste decreases.

On the Javanese Café Culture: Angkringan and Warung

But Centhini or other early 19th century Javanese literature above did not show what the shape of the place where people stop by outside the house to sipped a cup of coffee. The only depiction that can be obtained about what Javanese people like to enjoy coffee in public spaces in the 19th century until the early 20th century is through pictures, paintings, and photographs made in the colonial era. Not much that I can found from the collection of Tropenmuseum, KITLV, and Rijksmuseum, but the collection obtained seems to be enough to provide a preliminary analysis and description of Javanese lifestyle practices enjoying coffee.

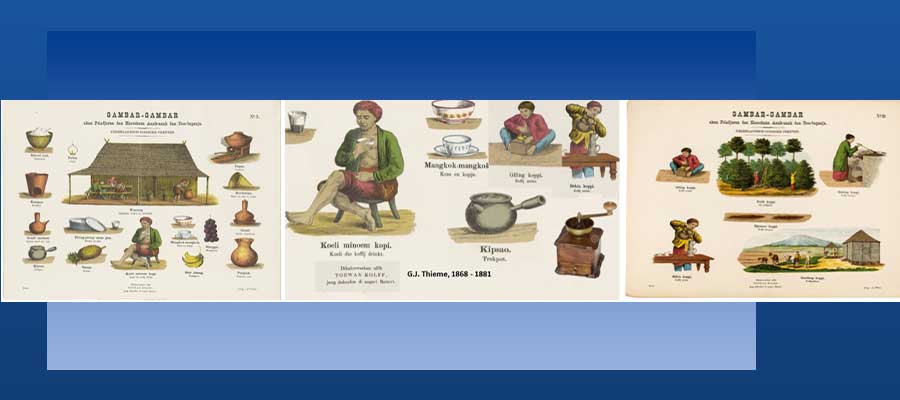

Nederlandsch-Indische prenten, nr. 5 & nr.10. Chromolitho. Impressum: Gualtherus Kolff/G.J. Thieme (Batavia/Jakarta/Bandoeng, 1868-1881). Collected from https://commons.wikimedia.org Accessed 05/10/2019

Pictures in “Nederlandsch-Indische prenten, nr. 5 & nr.10” can be a good illustration of what Javanese are associated with coffee in 19th century. In this picture we can see Javanese men and women working as coolies or workers in a coffee plantation environment. Their activities from picking, transporting, drying, roasting, grinding, brewing and serving coffee for their master to enjoy. And what’s interesting was the food stalls on the coffee lane road in the village, where the coolies and passersby stop by to rest, to enjoy a sip of fresh water or a cup of coffee and snacking or eating after laborious work.

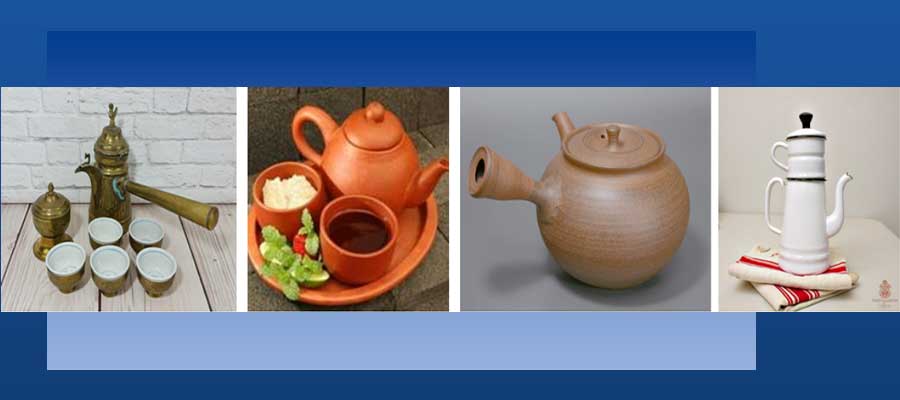

Left to Right: Dallah with handle- arabic, poci teapot & trekpot/kipsao- chinese, 1900’s cafetière Parisienne – European

Collected from Google Search – Accessed 05/10/2019

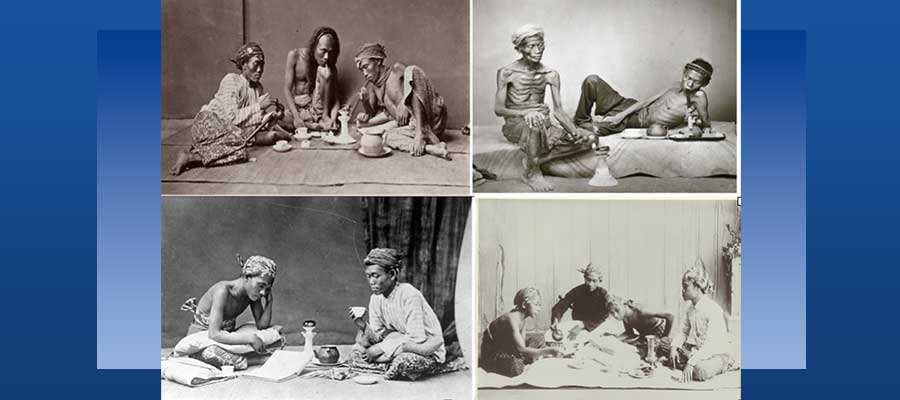

Interesting note to see the type of poci-pot and kipsao/trekpot in Java in the picture above and photos of the colonial period (which are also used for postcards; below) that seem to have their own uniqueness in their use among people in Java in the past. Since the colonial period until now, the poci-pot always connotes as a teapot to serve “nasgitel” (accronym “panas-legi-kenthel”; hot, sweet and thick) complete with rock sugar or brown sugar as its sweetener. While kipsao/trekpot (as seen in the colonial photographs taken in the photo studio ca. 1867-1910, possibly photographed by Kassian Céphas) seemed to want to emphasize the different uses of the kipsao/trekpot as compare to the poci-pot. From the analysis of the picture, I argued that the trekpot/ kipsao seemed to be identical in the presentation of coffee, while the poci-pot has remained as a teapot. Although in practice some people use the trekpot/kipsao to make “tubruk tea” as well, but once again the poci as far as I know seems to be rarely used to serve coffee. These photos below show Javanese people enjoying coffee and tea at home with classmates and in the cubicles of opium rooms.

Above – Below: smoking opium with friends; studying with friends

Left – Right: enjoying coffee with trekpot/kipsao; enjoying tea with poci pot

Collected from https://commons.wikimedia.org – Accessed 05/10/2019

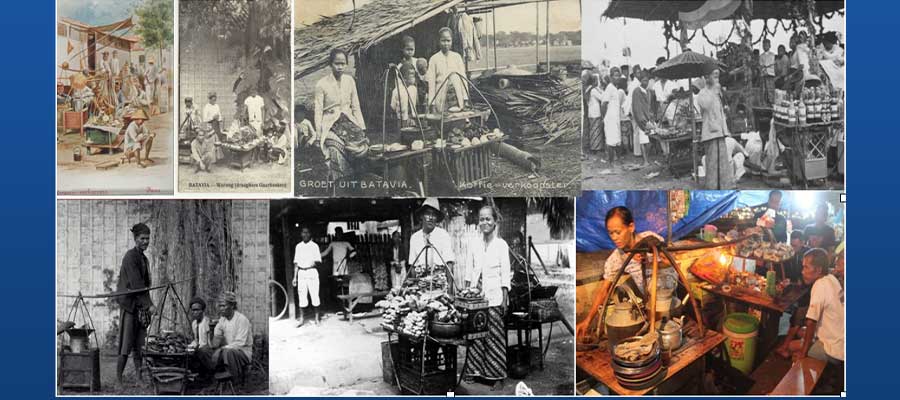

Then what about the situation of enjoying coffee in public spaces? Some photos that will be discussed below show many things about Javanese culture that have not changed much, in enjoying coffee in the 19th century until today. If we look at coffee hawkers in colonial Java (1880’s-2000’s) in the collage of images that I have collected below, it can be seen that there has been no major change in the Javanesse coffee hawkers style. Running for more than 200 years there was no development that led to a place like a café that gave birth to an enlightenment revolution like in Europe and even in the Arab world except as a release of routine and daily lifestyle. This street hawkers were always selling with various sweet and savory snacks, cigarettes, and meals. These vendors usually hang out in crowded places such as bus stations, train stations, office complexes, markets, in the field when there were crowded night markets, and so on. Meanwhile there are also more permanent coffee shops attached to the house, or a kind of hut / kedai with a menu that is not much different from the sidewalk, known as “warung kopi”. It appears that consumers or clients were the lower middle class not a group of santri/religious-students, intellectuals, or those in the upper middle class.

Coffee vendors in Java (1880’s-2000’s) collage of images from https://commons.wikimedia.org

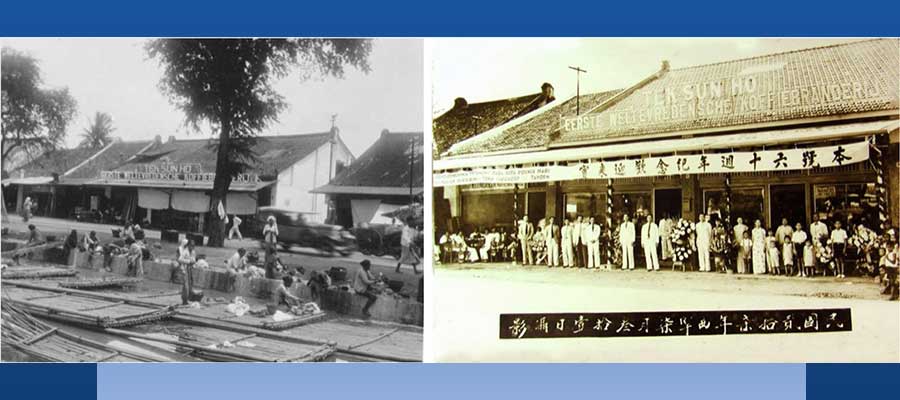

At that time, the oldest coffee shop in Java, Tek Sun Ho: Eerste Weltevredensche Koffiebranderij (Tek Sun Ho: First World Peace Coffee Roasting Company), was founded in 1878 by Liaw Tek Soen at Jl. Moolen Vliet Oost, Batavia, or now Jl. Hayam Wuruk, Jakarta. Formerly, in 1870s this coffee shop was still a food stalls and sold anykind of groceries for the lower class. Named as “first world coffee of peace” perhaps it was because in those days, this Tek Sun Ho coffee shop served and brought together Low and High-class tastes and customers, this continued into the 1930s. A unique position of this ethnic group in Java since ancient times, as a middle man. Tek Sun Ho from that time until now apart from being a stall serving people drinking coffee, also mainly sells their own roasting coffee grounds (Galikano, 2017). However, notes about the establishment of the café in Java seems to have only appeared in the 1930s. Modern cafehouses appear in big cities in Java such as in Surabaya: Café de Karseboom, Café Biljart de Kroom, Café Neutraal, and Café Biljart Tonny (Widodo, 2011, p. 179). Not much information can be obtained about what ‘life’ is like in the modern cafes of that time other than the imagination of the presence of ‘biljart’ (bilyard) in places where, in this case, shows as a place of leisure and upscale lifestyle compared to the coffee shops or hawkers that were base and around the city crowd. Need more in-depth research about the ‘life’ of cafes in the 1930s Java.

Left: Washing clothes along Molenvliet, Batavia. In the background was Tech Sun Ho. 1932.

Right: Tek Sun Ho Birthday in 1938 (Doc. Troppenmuseum)

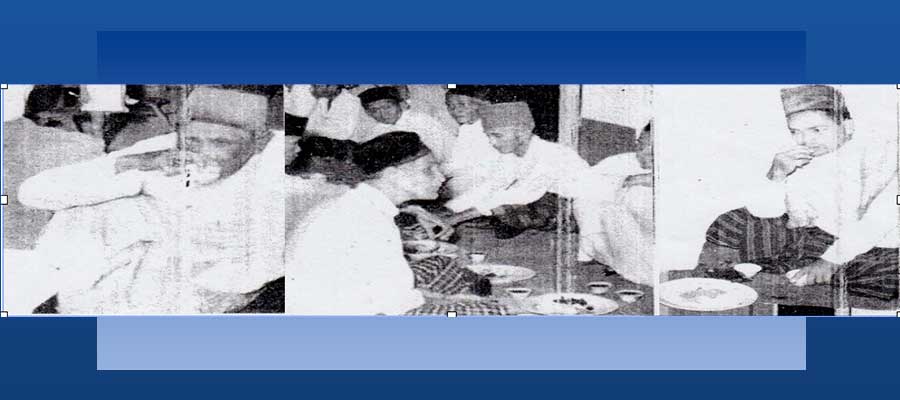

Meanwhile, in the village of Kauman, enclaves of Arabs and santri in urban areas in Java seemed to be the closest place with the world of Arabian coffee. From the picture that I got from D’Orient Magazine (1940), it appears during the fasting month or Ramadhan “arabic coffee” (spice coffee) served to break the fast by being served using a small cup (cup) as commonly used in the presentation of coffee in the Arab world. It is interesting that enjoying Arabic-style coffee is not much mentioned in colonial or Javanese texts except the term “wedang sherbet coffee” in Centhini above. However, it is not clear whether the coffee grounds used are the same as Arab / Turkish coffee powder (mixed with spices).

Ethnography in kauman Malang, which I did in 2017, also did not find the specific café stall or shop that sells arabian flavors. Except in kauman enclave there is a cake shop in Malang that also sell Arabian coffee powder which is thick with spices. For Javanese people the smell and taste of Arabic coffee is indeed not much different from the “jamu”, herbs-medicine. Indeed, qahwa coffee is still found in Arabian food stalls which can still be enjoyed in Arabian pockets (kauman) in Java (Ulung & Deerona, 2014) but it is not known for certain when the Arabs in this kauman complex opened food stalls and served qahwa. “The Arabs in Kauman usually serve this Arabic coffee at certain times, especially in the month of Ramadan to increase stamina and not get sleepy on the nights of worship in this blessed month,” explained the Arab coffee seller in Kauman Malang to the author. The event of enjoying qahwa in kauman was visually immortalized in the colonial magazine, D’Orient 1939 which is set during the month of Ramadan in Tanah Abang (Anonymous, 1940). This reminds us of the 19th-century Van den Berg’s account of coffee culture in Hadramaut. He found that the Hadrami Arabic coffee culture was centered at home, so they did not fovour the coffee shop (miqhayah) and they have a custom that when they visit they bring their own coffee for the host to enjoy together (van den Berg, 1989, p. 46). Hadrami people drink coffee as health supplements and inspiration for ritual worship. This could be one of the reasons why there was no Arabic ‘coffee shop’ style in Java. And ecause of the culture of drinking coffee they are private it makes them not enthusiatic doing coffee shop business. This condition might make the muslim Javanese coffee culture stagnant. Because, it must be underlined that the basis of the congregation and role models of Muslims in the cities and villages in Java have always existed and centered on the radius of the Arab scholars in this area.

Drinking qahwah using a kop during the Fasting [1939] at Tanah Abang Arab Village, From D’Orient magazine

Since getting to know this coffee plant in the early 18th century, farmers in the archipelago knew that coffee is a commodity sought by merchants from Arabia, India, Europe, and even China. Before the existence of forced cultivation, it appears in Centhini (1814 – 1823), the tradition of drinking coffee was present in Javanese society. However, when the forced cultivation system was treated (1830-1870) by the Dutch colonials this situation seemed to have blocked the direction of the development of coffee drinking culture in the archipelago, especially Java. The era of forced cultivation is what makes coffee a bitter curse for the lives of Javanese people. Therefore, it is not surprising that the development of the cafe culture stops at what has been discussed in the second section above. But the discussion above has not revealed what made the culture of coffee and cafe drinking in Java not develop. This discussion section will look back and forth at internal and external factors as to what caused the emergence of this coffee drinking culture.

Internal Factors

The first internal factor was for centuries the archipelago people always enjoy this coffee only for medicine and as a stamina enhancing drink to hold worship at night.

“[…] at the time of reading the Qur’an […] On this occasion tea and coffee drinks were also served, although usually these two types of drinks are considered to be good only for sick sufferers. “When entertaining guests,” The first thing served to guests is betel, then ‘jeumphan’ and other sweet dishes. Drinking coffee on that occasion is a habit that is really modern and gradually many people do (Hurgronje, 1985a, pp. 36, 271).

It is interesting that Snouck at that time did not record the existence of coffee vendors or coffee shops like Java. Furthermore Snouck noted that,

“Acehnese rarely drink coffee or tea in normal conditions, but when they are sick these drinks are used as a substitute for water, or at least the water is boiled first, a habit that is clearly considered good by Western medical science. Snouck explained that “The use of these two types of drinks in Aceh is mainly limited to foreigners living in Javanese villages and their Acehnese neighbors, or pilgrims who have become accustomed to drinking tea and coffee during trips in Arabia (Hurgronje, 1985b, p. 58).”

Javanese Hajj, in which they only knew that going for the hajj was a pious act and should not be confused and mixed with mundane matters. The focus was only on doing worship before God. It is not surprising that the ancient records of the pilgrimage (rihlah) until the 1950s mostly consisted only of worship procedures. Most of the Javanese pilgrims, as Snouck Hurgronje observed in (1884 – 1885), aside from the rich and priyayi pilgrims, were came from the village, naïve, innocent, resigned, and easy-to-believe what their their Hajj’s adviser said. They are even often deceived and depleted, therefore most of these lower class pilgrims could not enjoy qahwa let alone buy souvenirs like the pilgrims of today. It was clear that those who could enjoy kahwa were those who had a lot of money while performing Hajj like the priyayi, merchants, and of course their ulama. A person like a Sundanese Menak, R.A.A. Wiranatakusuma, who went for Hajj in 1924 could complaint about a coffee shop in Mina as he enjoyed qahwa, as he served with an unwashed cup (Chambert-Loir, 2013, p. 643).

Long before the 20th century, most of the archipelago who went on the pilgrimage were wealthy merchants as reviewed by Dobbin (2016). In the period before the 20th century the imagination and practice of drinking coffee (ala kahwa) on the pilgrimage was still seen as a remedy when the body condition was uncomfortable or unhealthy. Several times coffee drinks were also mentioned in the Chambert-Loir’s book (1954-1964 volume), that the coffee provided by the ship and their pilgrimage travel bureau really tastes bad, low quality. This is the second internal factor that made Arabic style of drinking coffee (kahwa) exclusively popular in Javanese muslim society (in kauman or santri) as a drug. So the Javanese coffee drinking culture discussed above is a culture originating from the fringe of coffee products, the leftover from the global market that is considered ‘wild’ by Gupermen. This form of wildness originating from the practice of drinking coffee clandestinely seems to be reflected in their flexible and easily transportable angkringan carts to pick up customers and especially, of course, if expelled by security and landscaper guards, not much different from today.

It is undeniable that coffee has become part of the Javanese dietary, especially the elite (priyayi) and santri. Even in Centhini this food and drink is also part of the Javanese religious world which is reflected in their rituals (Sunjata et al., 2014, pp. 149–151). Centhini explained that these rituals originate from the cognition and worldview of Javanese spirituality, which are mystical and magical (Ricklefs, 2006, p. 195). The salvation rituals or selametan become the background of the journey of the main characters of Centhini, which is set in an era when coffee plants began to become part of their gardens and lives. Along with sugar cane, tobacco and cocoa, coffee is also presented with rituals during the planting and harvest season, especially in large estates owned by Gupermen, the private sector, and local authorities. As an alien commodity, the ritual forms on this plantation must have been introduced to the farming community and workers by the elite as a new invention. As a ritual that has psychological power that binds self and social awareness to obey the symbols and meanings that exist (Hobson et al., 2018) rituals in the Javanese tradition display this world export commodity.

The offerings of the celestial ritual are a glass of coffee and sweet tea [sugar], candu [opium], cigarettes [tobacco], and various meals and jajan pasar snacks. It is an interesting analytical speculation on how the Javanese elite controls the cognitive and psychological awareness of their subjects. It can be seen that in the world of Javanese cognition and spirituality, coffee exists as a condition for offerings (an ambrosia) which are placed in specific places and times for extraordinary “figures” (unseen spirits, ancestors, and rulers) (Teggia & Hanusz, 2003, p. 121) whose power is able “threatening” the fate and lives of the Javanese and their offspring; especially if they are negligent and careless. These symbols and mystical meanings operate in the cognition of Javanese workers, workers, and farmers who unconsciously control their behavior. That coffee (along with other commodity sets commodities) is a sacred drink reserved for high spirits and rulers so that the best harvest is served to the ruler.

Not surprisingly, since colonial times until now in the pockets of coffee plantation villages in Java, for example in Malang and Jember, there is no different coffee drinking habits compared to those in urban areas. The complexity of the internal elements that occur in Javanese psychology is emphasized by external reality, where in enjoying this coffee, the Javanese seem to be forced and accustomed to enjoying low-quality coffee ores, are more accustomed to consuming coffee leaves, or brewing coffee dung droppings from mongoose, which they collected from their master’s garden. In addition, until now are accustomed to hearing from the mouth of Javanese parents who scold their children saying that it is not good for children because they cannot sleep, make it bloated, and it feels bitter even though there is sugar in it. The children must sleep and be healthy so that parents can work hard in the large garden for the gupermen and their masters every morning.

External Factor

Looking at the ‘ethnographic’ notes of Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje in Aceh 1891-1892 we can see that the tradition of drinking coffee in Aceh has only just begun, although this was from the data and perspectives of Snouck at that time. He recorded his fieldnotes in the midst of Aceh War (1873-1904). As in Aceh, even in Java until now when serving Arabian-spices coffee or sherbet coffee, only when people feel unwell or sick, indeed it is for medicine. Or at special times religious events such as a congregation of dhikr or semaan al-Quran, especially on the eve of Ramadhan or Maulud event. This is actually also a common tradition that can be found throughout the Nusantara or Malay santri’s` world.

News leaflets in Aceh that spread anti-Dutch rule that flourished in the early 19th century gave a picture of the ‘politics’ of coffee in Java and gave a little answer why there is no café tradition like in the Arab world and even India (for café culture in India see, Vēṅkaṭācalapati, 2006). The following is Snouck’s account of the coffee story: “The story can always be heard in Bandar Aceh from the mouths of the thousands of pilgrims (the Hajjs) who (in the past) traveled to Mecca back and forth to stop at the port, while some of them stayed long enough in Aceh “The story that also appeared in the Teungku Kutakarang leaflet collection titled Tazkirat ar-Ràkidin (Warning to those who remained silent) found by Scouck tells what was often said by the Javanese soldiers who were in Aceh at that time, that the power of ‘Kömpeuni’ (actually it has changed to Dutch Colonial Government since 1800) “wiping out all prosperity, peace and property. The inhabitants of the land they conquered made them slaves. Young people they make soldiers, people who are rather old they make coffee growers, young girls they make gundik or concubines, while those who are elderly they make household servants. For every birth, marriage and death they collect a dollar tax, plus many other taxes, while compulsory and various forms of extortion are unrelenting “…” behold, they say to the people of Aceh, to every approach, because Kömpeuni later will tell you to plant coffee, like they told the Javanese. You can’t drink coffee. You will also be told to do a corvée like the people of West Sumatra ….” (C. Snouck Hurgronje, 1994, vol. 1, pp. 60–61; pp.109; Vol.3, 418).

What was in the Aceh war era leaflets was in the range of the time when forced cultivation (Cultuurstelsel, 1830-1870) was imposed by the Dutch which inspired the birth of the Max Havelaar’s novel. A portrait of cruel exploitation, by indigenous and colonial rulers, towards the underprivileged people from being forced to plant crops for export. It was truth that Javanese and West Sumatranese are forced to plant the coffee, but they forbated to drink it. This was also witnessed by Casembroot in the late 19th century who saw the Javanese farmers drinking coffee leaves because they were not allowed to use their coffee beans (Casembroot 1887:21 in Breman, 2015, p. 309). This situation was even felt until 1928, along with the opening of the railroad lines in Java for the transportation of plantation products (and civilians) the ‘carriage’ drivers had decreased their income so that they could no longer enjoy drinking coffee and turning to drinking the coffee leaves. This is in the Semar, Gareng, and Petruk dialogues in the 1928 Kejawen Magazine:

Ing môngka anane sêpur saiki kiyi, pirang-pirang kancaku sing padha tiba ing mlaratan, kaya ta: Kang Wirya tukang grobag lan Kang Krama tukang dhokar, kuwi saikine padha malarat-malarat bangêt, tandhane dhèk biyèn anggêr tak dhayohi, wah, suguhane kampiyun têmênan, wedange: wedang tèh sintèk cap Sêmar, gulane: gula batu, pacitane: ondhe-ondhe têngkuwèh, krasikan, juwadah bintul, rôndha kèli, lan isih akèh manèh tunggale. Barêng saiki suguhane: wedang godhong kopi kathik ora nganggo gula, pacitane bêgja-bêgjane bakaran tela, tur anggone ambêdhol tandurane tanggane. Mara, apa aku ora nlôngsa bangêt ngrasakake kang mangkono kuwi.

That is, since the existence of this railroad, many of my friends have become poor, such as Kang Wirya, a grobag driver and Kang Krama, a dhokar driver, now they are very poor. The sign was that when I visited, wow, the dish was so lavish, such as: Sémar’s sintèk tea with rock sugar, the snacks: ondhe-ondhe têngkuwèh, krasikan, juwadah bintul, rôndha kèli, and many more. But now they only served: coffee-leaves tea without sugar, even its snacks, if lucky, only roasted-cassava, which they take from a neighbor’s yard. Am I not sorry for what happened to them…(Kajawen, 1928, p. 1230)

Jan Breman told of J.M. Esche, an official, who suggested prohibition on coffee. Esche (1891) stated that the prohibition should includes: drinking coffee! In his official note, letting coffee drinking habits increasingly popular in the community is a misplaced favorable treatment, because drinking coffee adds to their needs. Because all coffee products must be deposited to the Government for export and state treasury contents. It is necessary to search people’s houses so that coffee is not secretly consumed and becomes a habit, if necessary the police must act. And it was not surprised that this matter also existed in other districts in Java. Baardewijk’s records what happened in Cirebon:

In Cirebon the people were not allowed to drink coffee. To lend this measure some force, after a harvest peasants’ houses were searched for beans that might have been withheld from delivery to the warehouses. For a number of years the people of the Kuningan regency had to hand in all their kettles to the government. (Baardewijk 1994: 165-6 in Breman, 2015, p. 309).

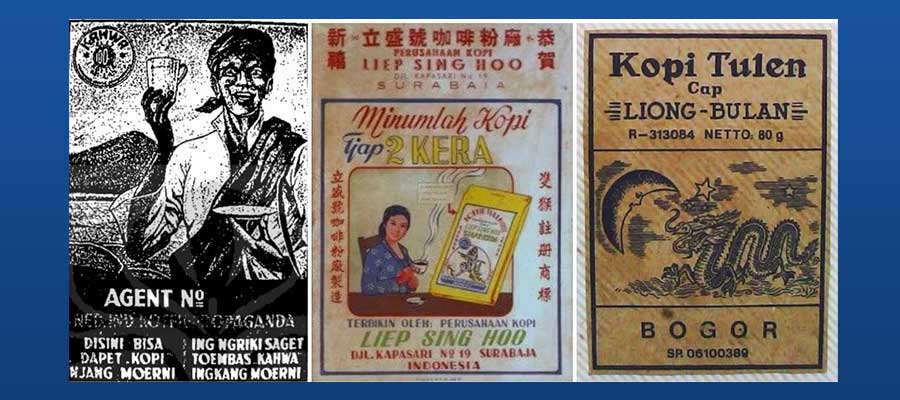

Other external elements also conditioned why qahwa and even coffee did not develop into serious cultures in Javanese society. Javanese coffee producers in the colonial period seemed reluctant and never seriously built their local markets. Because it will obviously reduce export revenues. It is seen that coffee advertisements have existed and massive in European media since the 17th century (Ukers, 1935, Chapter XXVIII) while in the Dutch East Indies, Java primarily, it was proven that there were no massive coffee advertisements in the mass media, unlike cocoa and cigarettes (Riyanto, 2000, 2019). For this reason, in 1937, coffee producers in the Dutch East Indies established the Koffie Propaganda Nederlandsch Indie along with the decline in the prestige of Dutch Indies in the world since the 1890s and worsened by the world economic crisis 1920 to increase coffee consumption in the Dutch East Indies. From this 1938 advertisement the Dutch East Indies government directly recognized that the local market was a low-class mixed coffee market and this had become a habit and a cultural flavor of its own. The inauguration program for this propaganda was finally inaugurated in 1940 at Societeit Constantia Madioen with the speaker Mr. Van der Spek published in De Indische courant, January 13, 1940.

The same propaganda was carried out in the Netherlands in 1940 (Rahma, 2016, p. 93). The first advertisement for coffee consumption in Java was made by this propaganda bureau, but it did not appear to be followed massively and creatively in the marketing promotion of coffee products both from the propaganda bureau and coffee producers in the Indies because World War II hit and then Indonesia became independent. Until the 1950s only “Kopi Tjap 2 Kera” produced by Liep Sing Ho, Surabaya and coffee “Tjap Liong” Bogor appeared in the newspapers.

Left to Right Coffee Ads by Koffie Propaganda Nederlandsch Indie in 1938 which provided information wher people could buy coffee that was more refined and pure compared to coffee in the market and only in the 1950s did Local Coffee Ads appear in the Mass Media

Most coffee shops in the colonial period such as Tek Sun Ho above only sell roasted coffee, grinding services, and ground coffee products for local consumption. The success of advertising for marketing still relies on word of mouth advertising. Compared to chocolate beverage advertisements featuring boys and girls, the visualization of coffee advertisements in Java that only began in the 1970s by the company ‘Kopi Kapal Api’ has always been targeting the adult market until now. In the Netherlands Indies children and old people are not a market segment of this world-hypnotizing beverage unlike Cacao and Tabacco.

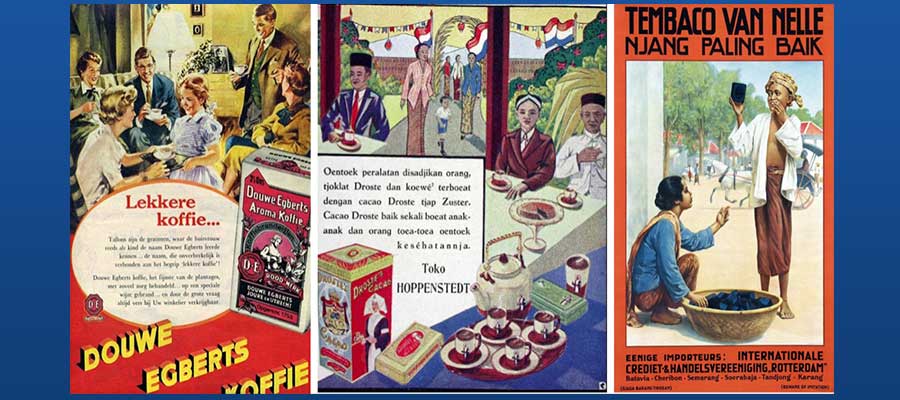

Left to Right: Ads by Douwe Egberts Koffie in Holland; Droste Cacao Powder and Van Nelle Tabacco ads in Java.

The absent of coffee ads in comparison to the Cacao and Tabacco ads in Java by the colonial.

Unlike in Europe, the Netherlands in particular, since the beginning of the 19th century, coffee advertisements are represented and targeted to all elements of the family and have even entered children’s books such as coffee curls produced by Alex Meijer (1840s), Egbert Douwes (1780) , Van Nelle (1782). These advertisements that made coffee became part of European life since childhood. It fosters imagination and creates various cultural innovations to enjoy coffee. It is from this passion for coffee that various forms of coffee cup sets, coffee mills, coffee makers, coffee containers, style serving and so on are created. While in Java, it still stalled at the most basic stage, namely the ‘tubruk’ coffee. From the past until now, in the upstream part of the coffee business, coffee farmers and workers in coffee and plantation companies are still strongly disciplined in the shadow of the company’s panopticon. So there is a fear of enjoying coffee from their work, and this is of course good morality, unless there is the approval of the supervisor and owner, as told by Rosa’s ethnography at the Jember coffee plantation (Rosa, 2016).

This is also reinforced by the fact that there were rules signed by local authorities and representatives of the Dutch Government regarding this export commodity product. This kind of regulation has been started from koffie stetsel in Priangan (1720-1830) which continued on Cultuurstesel (1830-1870) whose aim is to monopolize and prevent theft, embezzlement or smuggling. In the case of Surakarta, there are rules made between the Susuhunan and the Resident in 1895. It stated that it is prohibited for citizens from 6 pm to 6 am to bring with them: 1. green coffee beans, 2. coffee powder worth more than 10 cent, 3. Coffee leaves, 4. Godhong tom or indigo leaves, 5. Tobacco leaves, 6. Sugar cane without the permission of the district office and known to the local police (R. Sasradiningrat IV, 1905, pp. 116–117). There are even specific rules about storing, carrying, and selling coffee leaves. Those who violate this regulation will be fined f.25 or forced labor (given food) but without pay for three months. This rule is spread in places that everyone can read (R. A. Sasradiningrat IV, 1909, pp. 145–146). There is still a question, in addition to being made into coffee leaves, for what people actually use coffee leaves so there must be rules and restrictions from the authorities.

Conclusion

From the arguments of the discussion above, I argue that the process of diffusion of coffee culture in Java is not the same as the Arab and European world, where the process of trade and consumption of these beverage commodities has been rooted for a long time and has evolved miraculously. In Europe the lifestyle created by social spaces in these cafehouses feels maximum along with the spirit of enlightenment at that time (Melton, 2001) and long before in the Islamic world, the Ottomans in particular, the peak of their spiritual and intellectual culture was also embodied in this coffehouses sociability (Sajdi, 2014). The symbiosism of the café world and the elite society that lives it has created a unique drinking civilization and stimulated the intellectuality of its citizens. The imaginative and creative world created in these public spaces has become a real obsession to create a sophisticated culture of drinking coffee.

Meanwhile, it appears that the culture of drinking coffee in Java did not grow in the same direction as in Arabia and Europe at that time. This is because coffee is an export commodity which is politically and culturally, by the authorities, not to be consumed heavily by the Javanese themselves. Even internally and externally the culture of coffee consumption is curbed in such a way that it does not grow into a significant lifestyle, even among the upper and middle class elite. This is because consciously the rulers and middle class elites of the local Javanese elite at that time were even more busy involved in the realm of coffee production culture than the culture of consumption. This elite group is undeniably actively involved as an extension of colonial hands who enjoy the blessings of this coffee production wheel.

This does not mean that coffee culture does not emerge in Javanese society. The emergence of many coffee vendors in colonial cities throughout the 19-20 century turned out to be from this lower middle class. They process and consume fringe coffee products with low quality. These vendors become a gathering place for workers and laborers who are tired of daily life. The culture of drinking coffee in Java has become synonymous with the culture of eating to fill a hungry stomach, forgetting oneself from the bitterness of life. Their coffee-drinking lifestyle did not arrive at an enlightening reflective awareness, let alone revolutionized their worldview, because their spiritual cognition had been co-opted with the bitterness of life as laborers and workers. Unlike in Arabia or Europe where their coffee houses are filled with lifestyles of the educated middle class and above, politically influential, with an open passionate spirituality, far from the reality of fatigue and routine of life.

The adaptation of the culture of drinking Arabic coffee (kahwa) in Java seems to have stopped in the pockets of the santri (kauman) both in urban and rural areas who enjoy coffee only as a medicine when their body is uncomfortable and increases stamina when needed for late-night worship. Meanwhile the coffee production of the santri also takes part in the global economic circle as an export commodity whose profits, predictably, are for the provision of religious travel to the holy land (Dobbin, 2016; Tagliacozzo, 2013). And even if this coffee product is present in the discourse of jihadi farmers and local scholars often occur, this is due to the coffee economic injustice that is increasingly pressing their lives. The injustice caused by the abused of ‘cultuurstesel’ by local rulers together with representatives of the colonial government (Multatuli, 1972).

The glut of coffee economy in the ‘cultuursetsel’ system is what hinders the emergence of café-houses culture in Java. So that the culture of drinking coffee actually grew and emerged from the periphery of the cultural process of coffee production, not from the cultural process of coffee consumption among the Javanese elite at that time. Because they were absorbed in collaborating with the colonial authorities to pursue export production profits. This can be seen from the absence of promotion of coffee consumption in Java, which at the same time in Europe is intensively offered the pleasure of drinking java coffee for all ages. The presence of coffee vendors in large colonial cities at that time was even a classic urban problem of its own until now. The coffee vendors in these colonial cities, according to Basundoro, became a threat that had to be regulated and monitored so that the city remained comfortable and beautiful. The disobedience of the street vendors is due to the pursuit of their lives, which seemed to want to continue to express their existence and their resistance to the authorities (Basundoro, 2009, pp. 173–178).

In conclusion, while these Javanese elites enjoyed the bitter-sweet of their coffee in their ‘pesanggrahan’ or palaces, in cozy restaurants, and in societet-clubs with their European joint venture friends while discussing the increased production of coffee exports and other commodities. Most of the common people can only enjoy steeping bitter roasted coffee powder mixed with corn or stale rice. They drink coffee and eat as if releasing and forget the stresses of their lives as the clove cigarette smoke comes out of their mouth and nose. The separation and symbolic and meaningful differences in the class structure of Javanese society in enjoying coffee is what hinders the creation of imagination and creative obsession with their coffee world. The world of coffee in Java is produced from a darker side of luxury enjoyement in Europe, therefore unable to create a serious and fun self-internally café culture, technology, and lifestyle.

Therefore, from the findings and discussion above, it appears that even though the Javanese community is so close and intense in touch with the Islamic world, its contact with coffee turned out to experience, what in terms of Marxism, cultural alienation. The Javanese while enjoying coffee steeping turned out to have been alienated from the realm of meaning-making mode of production. In other word, they were alienated from the mode of consumption. They were alieanated from the lifestyle of drinking coffee itself. In the perspective of this transcultural diffusion process, it is clear that there is acceptance and intense engagement in this cultural of coffee production line, but the meaning-making production line in the enjoyment of consuming coffee is severely hampered, imperfect. These conditions and situations make the culture of enjoying sophisticated coffee brewing in Java a failure. As Steven Topic stated that indeed “Coffee is largely a social drug, and its sociability has greatly shaped the modern world” (Topik, 2009, p. 85) but ironically not intoxicated enough to be able to make a social and cultural change of the Javanese at the same era.

Acknowledgement

The author is grateful for the HPP-UB grant for this research, as well as for discussions with I Wayan Suyadnya and research team. Moreover, itinerant discussions with Mas Sisco Fx BB Hera enriched the perspective of this paper. Also unforgettable were comments and input from Prof. James Fox when the initial draft of this paper was presented at ‘Islam and Identity of Southeast Asian Languages and Cultures’, the International Conference on Culture and Language in Southeast Asia (ICCLAS). 14-15 November 2017 in the Syahida Inn at the Syarif Hidayatullah State Islamic University (UIN) in Jakarta, Indonesia

——-

Ary Budiyanto is lecturer at Antropology – FIB Brawijaya University, Malang, Indonesia. He received his Master degree from the Center for Religious and Cultural Studies, Gadjah Mada University. Now he is a doctoral student at Universitas Gadjah Mada. He is a co-founder, secretary, and researcher at the Center for Culture and Frontiers Studies (CCFS) and member of Wargakarta Research Group at Brawijaya University. He is interested in the issues of religions and cross-cultural studies, especially as related to Indonesia, Chinese-Javanese relations, Islam, Buddhism, Javanism, and modernity in the field of visual, material, and food studies. He has published his first book on Buka Luwur of Sunan Kudus ritual (Bahasa) and now he finished his second draft book on ethnoSOTOgrafi. He can be reached through arybudhi@ub.ac.id; ary91budhi@gmail.com; arybudhi@mail.ugm.ac.id

——–

References

Alamsyah, Y. (2006). Kue basah & jajan pasar: Warisan kuliner Indonesia. Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Allhoff, F. (2011). Coffee – Philosophy for Everyone: Grounds for Debate (1 edition). Wiley-Blackwell.

Anonymous. (1810). Damarwulan—C. 1810 (Vol. 94). https://www.sastra.org/kisah-cerita-dan-kronikal/cerita/1053-damarwulan-anonim-c-1810-94-pupuh-34-48

Anonymous. (1940). Poeasa—Mohamedaansche Vasten. D’Orient, Batavia-cent : Petjenongan. http://opac.perpusnas.go.id/DetailOpac.aspx?id=58268#

Arvian, Y. (2018). KOPI: Aroma, Rasa, Cerita. Tempo Publishing.

Ashby, C., Gronberg, T., & Shaw-Miller, S. (2013). The Viennese Café and Fin-de-Siècle Culture. Berghahn Books.

Azra, A. (2013). Jaringan ulama: Timur Tengah & kepulauan Nusantara abad XVII & XVIII : akar pembaruan Islam Indonesia.

Badil, R. (2011). Kretek Jawa. Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia.

Basundoro, P. (2009). Dua kota tiga zaman: Surabaya dan Malang : sejak zaman kolonial sampai kemerdekaan. Ombak.

Breman, J. (2014). Keuntungan Kolonial dari Kerja Paksa: Sistem Priangan dari Tanam Paksa Kopi di Jawa 1720-1870. Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia.

Breman, J. (2015). Mobilizing Labour for the Global Coffee Market: Profits from an Unfree Work Regime in Colonial Java. Amsterdam University Press.

Brouwer, C. G. (1999). Dutch-Yemeni Encounters: Activities of the United East India Company (VOC) in South Arabian Waters Since 1614 : a Collection of Studies. D’Fluyte Rarob.

Bruinessen, M. van. (1998). Studies of Sufism and the Sufi Orders in Indonesia. Die Welt des Islams, 38(2), 192–219. https://doi.org/10.1163/1570060981254813

Bulbeck, D., Reid, A., Cheng, T. L., & Yiqi, W. (1998). Southeast Asian Exports Since the 14th Century: Cloves, Pepper, Coffee, and Sugar. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Chambert-Loir, H. (2013). Naik haji di masa silam: 1954-1964: Vol. I–III. KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia) bekerja sama dengan École française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), Forum Jakarta-Paris, Perpustakaan Nasional, Republik Indonesia.

Cowan, B. W. (2005). The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffeehouse. Yale University Press.

Daḥlān, I. M. (2009). Kitab kopi dan rokok: Untuk para pecandu rokok dan penikmat kopi berat. Penerbit & distribusi, Pustaka Pesantren.

Dobbin, C. (2016). Islamic Revivalism in a Changing Peasant Economy: Central Sumatra, 1784-1847. Routledge.

Dongeng Kopi. (2016, October 28). Kopi Talua, Menikmati Kopi di Tanah Minang. Dongengkopi.ID. https://dongengkopi.id/kopi-talua-menikmati-kopi-tanah-minang/

Ellis, M. (2011). The Coffee-House: A Cultural History. Hachette UK.

Faruqui, M. D. (2012). The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719. Cambridge University Press.

Fasseur, C. (1991). Purse or Principle: Dutch Colonial Policy in the 1860s and the Decline of the Cultivation System. Modern Asian Studies, 25(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0026749X00015833

Galikano, S. (2017, September 28). Bakoel Koffie, Ikhtiar Melanjutkan Garis Kopi. Sarasvati. https://sarasvati.co.id/food/09/bakoel-koffie-ikhtiar-melanjutkan-garis-kopi/

Gong, G. A. (2014). Air Mata Kopi. Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

Hanna, N. (1998). Making Big Money in 1600: The Life and Times of Isma’il Abu Taqiyya, Egyptian Merchant. Syracuse University Press.

Hanna, N. (2003). In Praise of Books: A Cultural History of Cairo’s Middle Class, Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. Syracuse University Press.

Hansen, V., & Curtis, K. (2008). Voyages in World History (Vol. 2). Cengage Learning.

Hanusz, M. (2000). Kretek: The Culture and Heritage of Indonesia’s Clove Cigarettes. Equinox Pub.

Haryono, T. (1998). Serat Centhini Sebagai Sumber Informasi Jenis Makanan Tradisional Masa Lampau. Humaniora, 8. https://www.neliti.com/id/publications/12226/teori-linguistik-tradisional-jawa-dan-masalahnya

Hattox, R. S. (1985). Coffee and Coffeehouses the Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East. University of Washington Press.

Ho, E. (2006). The Graves of Tarim: Genealogy and Mobility across the Indian Ocean. University of California Press.