(Part III) In The Mood for Urban Culture : The Romance Comics of Jan Mintaraga

Oleh Seno Gumira Ajidarma

The short version of this paper first published as proceedings from 2nd International Conference on Strategic and Global Studies (ICSGS 2018); part of publications in Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research. Publication Date: November 2019. DOI https://doi.org/10.2991/icsgs-18.2019.10.

Editorial assistance for this long version was provided by Jennifer Lindsay. Published for the first time in borobudurwriters.id. The Indonesian language version, with much more research materials will be published in hard copy later.

Abstract:

The art of comic narrative lies in the combination of pictures and words. The romance comics that Jan Mintaraga (1942-1999) wrote and published from 1966-1971 in the early years of the New Order, reveal the hegemonic process of Jakarta becoming the representation of urban culture. The determination of power and ideological struggles formed the setting, plots, and lifestyle of urban culture in the making. Taking thirty-eight Mintaraga comic titles as source material to investigate social, economic, and political discourse, I find that the dialectic between the dreams and reality of the past can be useful for a consideration of urban life today. The experimental culture experienced at that period, including the role of niche-markets, is returning at the start of the digital age.

Keywords: Urban culture, hegemony, ideological struggle.

PART III

29. Pauline (128/1971)

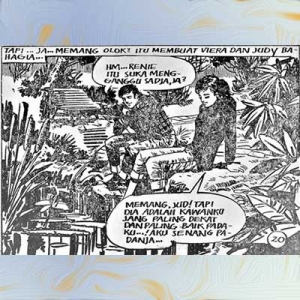

Pauline has a boyfriend, called Dolly, a singer in a band. Pauline’s mother does not like him, and prefers Benny, the son of her boss. One day Pauline has to cancel her date with Dolly, because Benny and his parents come as guests, which leads to her mother forcing her to go out with Benny. It turns out they meet Dolly who is out with Connie, and Dolly is angry and rude to Pauline. Their relationship cannot continue, but Benny cannot win Pauline’s heart either. We are told many young men want to get closer to Pauline, until she thinks that every male is a nuisance. With this attitude, in a business district she slaps a young man who bumped her and made all her books fall. It turns out that this young man, Permadi, is part of the subplot: Marsiti, the maid in Pauline’s house, has a sad story that she had to give up her son, who was born out of wedlock, even though she and the father of the child then married, because she could not bear the psychological pressure that she had humiliated her family. However, as she confesses to Pauline, who she has cared from childhood, that she is happy enough to live as a maid even she herself is from an aristocrat family. It turns out that Permadi, the young man who struck Pauline, is Marsiti’s son, and at that moment he was in a rush to follow Marsiti who he saw in the market. Permadi appears at Pauline’s house looking for his mother To Pauline who recognizes him, he admits that he works as a driver. By chance, Pauline hears Permadi ask her mother to come with him, and he promises that he will provide her with all the luxury in the world. When Pauline’s mother comes home from a business trip, she says some details are still waiting for the director-president of the business partner, because he is away, but she saw a portrait in his office that was just like Permadi. Meanwhile, Permadi confesses to his mother that he fell in love with Pauline from the moment they collided. As Pauline herself is already attracted to Permadi, her mother says there is nothing in their way, because they are from the same social class. H

Sets: First Pauline and Dolly meet on the pop music scene, as Pauline is one his fans, but as soon as the set moves to Pauline’s house, where her mother wants to dominate her future, the position also changes. Dolly is not the favorable person anymore. So, the world outside the house is wild and unpredictable, like Dolly’s attitude, but then also Pauline’s, when she happens to slap Permadi. In the house, Marsiti tries to hide herself behind the establishment, while the reality outside still finds her. The interior is not separated but instead part of the wholeness of the urban space that is always changing.

Story-enablers: When Pauline-Benny go out and meet Dolly who is with Connie, Dolly’s rude reaction of Dolly is unexpected, because Pauline has been arguing with her mother in favor of Dolly.

Theme-markers: Permadi comes to the house after the subplot of Marsiti’s story and Permadi’s collision with Pauline has happened, which makes the narrative more exciting.

Emotional-foci: The highest peak of the dramatic construction is the fact that Permadi is the director president of the company which Pauline’s mother, as a businesswoman, has recent business dealings with. When Permadi’s and Pauline’s hearts meet, it seems like everybody wins.

Signification: With the social hierarchy issue integrated into the whole plot, as part of the elitist old generation ideology, it is expected that the young generation will be against the idea that a married couple should be from the same social class. In this title, the young generation like Benny are not only in the same boat as his parents, but also against the culture of his peers. When it turns out that Permadi is Marsiti’s son, this does not make the social construction collapse at all, because Marsiti comes from an aristocratic family, and Permadi with his high position in a big company is of course now more than acceptable in Pauline’s mother’s point of view.

30. Pemuda dalam Tjermin (Young Man in The Mirror) (190/1971)

In the past, meaning 18 months before the present time, Nia was Arif’s girl friend, but she left him after he tried to rape her. She moved far away from her below average neighborhood, where Arif and the gang lived their low life and were involved in crime. At the start of the present time, Arif’s older brother, Budiman, has come to the place where Nia works, a music store. He says that Arif is in custody accused of murder, but that Budiman doubts it. It is hard for Nia to think of Arif because it makes her relive her pain, but she is attracted to Budiman, who feels the same way. With Budiman, they investigate the case in the neighborhood, facing all the threats from the gang which involved in organized crime. At the end, when Nia is being held at the gang’s place, Budiman comes with the police. After the investigation, Arif is found not guilty of murder, but he still has to stay in prison for his involvement in the crime. Arif is mad with Budiman who he accuses of stealing his girlfriend. H

Sets: This kind of plot gives the narrative two kinds of sets, the place for the common people and for the bad ones. The first is the regular urban dream of modernity and luxury, with the interior design that Nia confesses from Home Decoration magazine. The other is intended as the set for the bad guys, dark and gloomy places, yet always clean of trash which seems like part of the urban dream.

Story-enablers: The flash-back of Nia’s past with Arif comes to fill the drama needed after the encounter with Budiman. Then it is difficult to get information about Arif, whether he really did the killing or not, because the gang always violently gets in their way.

Theme-markers: As Nia gets closer to Budiman, the danger becomes closer as well, until the gang kidnaps her. When Budiman comes with police, the investigation finds the clue, and the relationship is definitive.

Emotional-foci: It is said from the start that Budiman lives and works in Singapore. So now what is the fate of the love couple? After all the tension, is this an anticlimax because they have to separate? The end is a happy ending: Nia agrees to leave her job, and goes with Budiman, who is ready to buy a couple of rings at Singapore airport.

Signification: The romance in this title blends with the flavor of a crime story, making a clear division between good and bad, so that love is not going to happen on the bad side, while at the same time this is part of the urban life in big city. Metaphorically, the dark and gloomy sets define the place of the bad side that also come from a low class, even fortunately showing that there are good people as well, like Nia herself.

31. Sesudah Badai Reda (After the Storm) (380/1971)

When Judy’s father suddenly dies, he leaves his son Judy a wealthy company, and Sati, his young wife who was Judy’s girlfriend before she married his father. It turns out that having an ex-girlfriend as his stepmother makes him frustrated, and he lives a dark life without any direction for the future. After taking over his father’s company, Judy’s life is drowned in the business world, which makes him wealthier than ever, but cannot heal his wounded heart. As a rich young man, he has money to stay in hotes, surrounded by professional girls who are more than willing to be his future wife. In the meantime, Sati uses her wealth that Judy’s father left her to travel and stay in big cities around the world. Along the way, the issue of insanity in his family comes and goes in Judy’s mind and sometimes he talks about it, saying he does not want a child who he afraid might be insane too. One day Sally comes along and becomes his wife, and after a while Sally gives birth to Lisa. Unfortunately, Judy does not change his habit of staying in the hotel with his nightlife style. Then Judy jumps into the movie business, until differences force him to become a film director and use Sati, who has returned to Jakarta, as the leading actress. The film becomes an instant success, while Sati and Judy have a difficult relationship because of their past. The result is that at the peak of her fame, the drunk Sati dies in a car accident. After some film business loss, Judy returns to success with a new star, Martha, who it turns out he knew was smuggled by his partners to replace Sati. Martha almost became his wife, but failed when—because of a blackmail attempt—she confessed the she was a porn-star before, but she does not admit other facts, including that she was a prostitute at 21, had a abortion, and now cannot have children. Apparently Judy already knows her story, and this last fact, regarding the insanity issue, makes Judy willing to marry Martha. However it turns out makes Martha run away, leaving Judy with a picture of Sally and Lisa in front of him. After a quarrel with Djupri, the older woman who already left because she could not bear to realize Judy’s life, Judy does what he thinks right: he sells the company, then joins Sally and Lisa as a family with their own home. H

Sets: The division of social space into high and low society does not reflect the division of moral stereotypes like good and bad people. In this title, the social space of high society is an urban dream filled with people with questionable morals, even without hypocrisy, which also happens in the slum with the low society.

Story-enablers: The meaningful flash back is that Sati was Judy’s girlfriend before she married his father. All the extreme attitudes of Judy, which become the strong motives in the plot, have the source in that past.

Theme-markers: When Sally enters the scene, the questionable morals of the main characters are contested by unquestionable morals, like Sally’s insistence that if the are married, as a family they should stay together in their own house. This moral stand easily overlaps with the questionable again, when Sati and Judy seem as though they are together without moral clarity.

Emotional-foci: Towards the death of Sati, it is the very tragic plot of a woman in search of happiness in a world of illusion. Her death is a climax, but this is not the end. The reader starts again with Martha, until there is another dark climax about her past. Fortunately, after facing the reality of what Judy thought was insanity, things suddenly become normal.

Signification: The representation of the urban this time does not have the obsession of showing what a metropolitan city is, but goes beyond physical phenomena, deep down to the characters on the crossroads of love and money. Nearly all the characters have new attitudes on life in the big city that seem to be not about love, but about efforts to buy back love through wealth and stories of success. The result is the dark and gloomy mood of the urban people in search of happiness facing great difficulty, and not everybody will succeed.

The dark and gloomy mood of the urban people in search of happiness.

32. Di Antara Serigala (Among Wolves) (192/1971)

Elsa comes to Jakarta to work at The Moonlighter nightclub as a singer. At the airport she is picked up by Anas, Drajat’s body guard. Drajat was the owner of The Moonlighter, a legal business among his many other illegal business activities. Today he is going to be buried because of a car accident the night before. That is why Benny, the detective who was Anas’s classmate in highschool, is investigating the cause of the accident. Still on this day, Elsa and Anas go to swim at the beach, and make a romantic impression on each other. That is why Anas urges Elma, Drajat’s young widow with whom he had an affair before, to keep The Moonlighter open, despite Elma wanting to close and sell it to the highest bidder. Because of the known links with the underworld, this is not easy. The only person interested Dicky, Drajat’s right hand and Elma’s enemy in the past dealings of Drajat’s business. Given this situation, Elma keeps The Moonlighter open, but also because she has a hidden agenda for Anas who she cannot forget. Meanwhile, Benny comes closer to Anas and rather suspicious of him, who as Drajat’s bodyguard should have been near Drajat all the time. Benny reveals his suspicion to Anas, so Anas investigates from the inside, and ends up finding out that it was Elma, and not Dicky who nearly killed Elma before being killed by Anas in an act of self-defence, behind the mysterious accident. Benny then asks Anas to join and help him in the police squad, but Anas says that he has to ask his future wife first. H

Sets: All the sets are the urban dream, the beautiful luxurious Jakarta, exterior and interior, are explicitly mentioned by Elsa as a newcomer to the metropolitan city. The harbor full of yachts and the surrounding setting seem to corroborate the luxury, until in the end after she falls in the water she says the opposite.

Story-enabler: The two subplots of flash-backs take on the past of Anas. First, his past affair with Elma makes Elsa curious all the time. Second, his past history of friendship with Benny, when now they are on opposite sides creates questions of how friendship should be.

Theme-marker: One crucial point is when Elsa sees Anas and Elma kissing in the distance., She does not really know that Anas seems dominated by Elma, because Elma canceled the closing of The Moonlighter only after Anas asked her to, because he is concerned about Elsa’s losing her job. Another point is when Dicky aims his gun at Elsa and overpowers her, before Anas and Elma come with a car and hit a wall. After a fight Dicky is killed by his own gun, so Anas thinks they have to run.

Emotional-foci: Elma is ready to shoot Elsa, but not knowing Elsa is a good swimmer in the ocean, she prefers to push her, to show her rivalry and that now she has won as she also shoots at the surface of the water.

Signification: The romance here is blended with crime story, which makes the urban a place of doom. Elsa even asks herself, what is the chance of love in an environment that is so full of hatred and suspicion. But the irony is in a way already revealed at the beginning, when the reader is told that Elsa is amazed by the city scenery and expects her life will change to be the start of a bright future, even it does not tell of what happened in her life before. The love story is confronted by life’s realities, which almost bury love as sincerity, and interpersonal relationships are part of the struggle for survival or to find momentary pleasure.

33. Anita (128/1971)

Anita and Nana are models and buddies. In the modelling world there are also Aries, a male model, and Bobby, a cameraman who is falling in love with Anita. Unfortunately, Anita is more attracted to Aries, while Aries seems to be going steady with Nana. Meanwhile, Nana has an aunt who lives near Anita’s place, who pays more attention to Anita than Nana. One day, Nana’s aunt asks Anita to come over, she is sick and tells Anita to take a diamond necklace from the cupboard after giving her the key. When Anita opens it, Nana enters the house with Aries. At that moment Nana’s aunt passes away. The accusation is taken to court, and while it proven that the facts do not support the accusation,, Nana still gossips around to discredit Anita. Meanwhile, Bobby is trying to get closer to Anita, who is already thinking that she must forget Aries. So she tries to love Bobby. However, it turns out that Aries and Anita find their way together, which makes Anita feel guilty, while Aries always tells her that they must be honest and talk frankly to Bobby. At this stage, Bobby is burnt in n accident, so that his eyes have to be covered and he must stay in hospital. At this time, Nana nearly drowns in a river, but Anita saves her, so that their relationship recovers. Anita thinks that is not morally right to leave Bobby in his condition, which makes Aries frustrated and he decides to go far away and forget everything. But when Anita comes to the hospital, she finds that the blindfolded Bobby and a nurse have fallen in love. At the airport, Anita manages to reach Bobby, who suddenly cancels his flight. H

Sets: As Anita, Nana, Aries are models, and Bobby is a cameraman, the outdoors where they work to make the images are the sets for the encounters. The others are the usual interiors with modern design, including private rooms. The outdoors also becomes the place where Anita saves Nana from drowning. Meeting places for the romances, like parks and clean paved roads with modern houses in the background, in the night with full moon, definitively direct the images of the romantic urban. Added to these facts is the first romantic meeting of Anita and Aries which takes place in the outdoors in pouring rain, then Aries gives Anita a lift in his car. The combination of nature and culture gives them a new chapter.

Story-enablers: Without any flash-backs, the dramatic enabler is the thought in Anita’s mind that she really loves Aries, but feel hopeless about the future, while when she is going steady with Bobby she still confesses to herself that she must try to love him.

Theme-markers: When Aries seems to be falling in love with Anita, while Anita is committed to Bobby, the question of whether that she will leave Bobby or not becomes like a suspense, which escalates after Bobby has the accident.

Emotional-foci: It seems as though being loyal is the best thing for Anita, but this suddenly comes to ruins when, with his eyes closed, Bobby thinks that Anita is the nurse with whom he is in love. At that moment, Bobby talks about how to inform Anita about the situation. With the knowledge that Aries has maybe already left, this is an emotional factor that leads to a climax when Anita reachs Aries on his way to board the plane.

Signification: The title shows that Anita the person becomes the site where the ideological struggle takes place, with moments of doubt that in a way reflect the urban process where there is no fixed standard of any values. In this title, Anita can reflect upon the individual in the urban culture who always has to choose among confusing choices. What becomes the happy ending does not guarantee it will last, because everything in the urban city is always changing for better or worse.

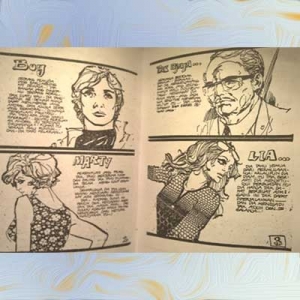

34. Rumah Djahanam (The Damned House) (320/1971)

In the house live the wealthy Pak Djaja, who spends most of his time working outside; Marty, who at first seems to be his daughter, but turns out to be Pak Djaja’s mistress who has been in the house from the age of 15, disguised as the oldest of the children; Lia, who knows everything but cannot do anything about it; Boy, the most vulnerable teenager, victim of the situation; Mama, the mother who has no choice but to stay for the children; and Jo, who should be Boy’s girlfriend from their school. Near this house is another house nearby a modest one, where Sumi lives, with Tino, her child born after Pak Djaja raped her when she was his secretary about six years ago. Sumi opens a kiosk, where Amran, Boy’s teacher who is attracted to her, often comes by, and meets Boy who always cuts class. The drama starts when one night, Boy, a first year high school student, sees what Marty is doing with his father in Marty’s room. Boy then becomes very rebellious, plays hooky from school, and is rude to Marty, until the reality is revealed by Lia, and then Mama. Knowing all this, Marty takes action by seducing Boy, which calms Boy down. Marty also threatens Sumi, saying not expect anything from Pak Djaja, and certainly not to expect anything from him. Then it is Lia’s turn to be frustrated, because after the relationship of her father with Marty, she cannot accept that Marty has tamed Boy as well. After a physical fight with Marty, Lia chooses to move to her grandmother’s house in Surabaya, followed by Mama who cannot allow Lia to go alone. In the now empty house, the confused Boy finally rejects Marty’s approaches and goes out driving his daddy’s new car. He speeds recklessly until he kills a becak driver. Although his father asks him to lie to protect his good name, Boy calls the police and reports himself. At the damned house, behind the gate he sees the police car coming to arrest him. UH

Sets: In this title most of the drama which is constructed by the ever conflicting urban values happens inside the house. Intended to depict a high class family, the interior design has the modern touch, from the furniture, wall decorations, and private rooms. There is also a part with a swimming pool to make the image definitively of high class society. All the moral sensational drama happens in that house. That makes the other neighboring house, which is also a kiosk where a victim of the high society lives, the alternative choice because that is where moral standards still surviv.

Story-enablers: Marty’s past, that she has lived in the house since she was 15, coming first as a maid seems like a threat for all the occupants, and from time to time she is able to dominate the house.

Theme-marker: It looks as though the only one able to resist Marty is Boy, which makes the tension escalate after Boy is compromised. Lia then becomes explicit and violent when she expresses her anger in a way that nobody expected.

Emotional-foci: Fatalistic enough, that Boy speeds up the new car as the catharsis to his anger, but still his act brings an emotional effect, even after the collision, because it iss clear that Boy is the most naïve of all the victims.

Signification: The interest of this title is that the drama is played almost completely inside a house, while the connection with the outside world is very limited. Practically there is no romance, or romantic relationship is not the subject, but human relationships are, where the political factor determines the nature of the relationships. So the urban process here does not really relate to the grand scenery of a modern sparkling environment, which urban people use like a stage for the story of their life; but rather to the conflicting ideology of the persons inside the house as the miniature that reflects the world outside.

35. Terdjebak (Trapped) (256/1972)

Lucy is married to Karel, a successful architect who is seldom at home, and every time he does come home does not really care for his wife, but only his own interests which are related to his business. Lucy is aware that this kind of thing creates a community of lonely wives who always gossip about each other’s adultery, and she thinks that she is not one of them. Lucy always thinks that she really loves Karel. It turns out that she falls for Josie, a fashion designer, and she lives a double life, just like her friend who has a much older husband. Dinah tries to kill herself because her lover is only an impostor who tries to blackmail her. In Lucy’s case, it not her lover Josie, but Anie, who shared Josie’s childhood as a streetkid who blackmails Lucy. It is said that Josie really loves Lucy. One night, the suspicious Karel catches Lucy by surprise, but Lucy is already preparing for a divorce. The angry Karel takes Lucy and drives his car at excessive speed, as though wanting to kill himself and Lucy. Lucy jumps out of the car before it is too late. Karel’s death makes Lucy feel very sorry, even understand that she does not love Karel anymore. She decides to break up her relationship with Josie. The latter, in his frustration, falls from one woman’s lap to another, never intending to marry. However, after some time, realizing Josie’s love, and her love for Josie, Lucy, who still keeps the key of Josie’s house, finds him again. This time to stay forever. H

Sets: Beauty parlor is where all the high class wives go, and from there they construct their world, where the circulation of gossip takes place. Included in this chain is a boutique house with people inside who also become the more important part of the plot. As the main character in the story is married to an architect, the interior and exterior of the house is like a showcase for a make believe effect. The irony of course is that in the house there are hardly any encounters between the couple.

Story-enabler: The act of blackmail underlines that romance as an extra marital activity is wrong. What happens to Dinah it’s also a warning for Lucy, that love, more than anything can go wrong. With the information that Lucy really loved Karel, a romance problem arises and asks to be solved.

Theme-markers: The problem is apparently reversed. On the blackmailing of Lucy by Anie, the couple having the affair, Lucy and Josie, really love each other, and Lucy is even thinking of a divorce—this makes Lucy being caught out not really matter, but the death of Karel does matter because of Lucy’s guilty feeling.

Emotional-foci: Lucy sacrifices her love of Josie for a moral that she is the one who is unfaithful in marriage. This makes Josie frustrated and fall for meaningless relationships with many women, until one day Lucy appears in front of him. This time forever.

Signification: In the urban world, traditional moral standards are shaken, and never replaced with new ones. The discourse of love is always conflictual. Love is not automatically faithful and faithfulness is more about morality than love itself. So which one is the trap? The romantic relationship inside or outside the house? The people trapped in the relationship that is traditionally wrong one are happy with it, as long as love matters. The ethical problem is about difficult choices: How ethical is it to keep a household without love? What is so wrong after all if love matters? The urban world standard values are never clear.

36. Hancurnya Sebuah Tirani (A Tyranny Shattered) (34/1979 [1969])

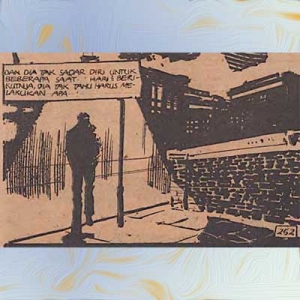

One night a motor boat brings Harris to a dock. Nobody is there – only wooden houses and the sound of the waves smashing the wooden dock. Nobody is there to pick him up on the day of his release from jail, where he had gone as the accused to protect Anwar, his younger brother who had killed a man. Tinah who loved Harris was the cause of the murder which happened five years ago. At the time, Anwar and a fisherman were fighting over Tinah until Anwar stabbed him with a knife. Because Anwar was still under age, Harris took the blame. Now at the dock appears old Kasim with an old car. They embrace each other and exchange news. It is clear that Anwar, like Harris five years ago, is still living in the underworld of smugglers and illegal activity, even though Anwar promised to stop that fives year ago. When they meet at Anwar’s palatial house in the middle of the poor district of fishermen, it becomes clearer that Anwar only wants to continue with his work of smuggling, robbery, and extortion. Anwar has taken Daeng’s goods which makes Daeng’s—an old ally in the gang—life suffer. For Daeng himself, this is the last unlawful activity which he did for his children’s education, but now Anwar does not want any ally any more. He wants to dominate all the underworld business in the area. In Harris and Anwar’s meeting, Anwar says that his mother only had one child, and that is him. Harris and their sisters, Fatimah and Latifah, are all adopted children. So Anwar demands the inheritance their mother left, after saying that Harris can stay in the old house, which Harris rejects because he promised their late mother to use the inheritance money to build an orphanage. This is not the only argument they have. When Harris asks about Daeng’s goods, Anwar says the goods should be in his possession. Harris asks to buy them, and Anwar seems agree, but Tinah warns Harris later that Anwar will never keep his promise. This is the same as Harris’s hunch, so he continues to practice his knife-throwing, which is his special skill. Coming back to the old family house, Harris hears the story that as soon as Anwar found out that Fatimah was not his blood sister, he tried to rape her,but Kasim saved her. That is why the sisters left as well. But now they have come back to greet Harris, with Budi, Fatimah’s boyfriend. One day that couple mysteriously disappears. At the appointed time, Harris shows up at the house that is full of the gang, and asks for Daeng’s goods which he knows from Tinah are not there anymore. Anwar wants Harris to give the money, but Harris wants Anwar to show the goods. Harris refuses and shows that he is holding Fatimah and Budi hostage.In a situation of an exchange of angry words, Tina warns Harris that Anwar will shoot, but Harris throws his knives and kills all Anwar’s gang members. He hesitates about throwing a knife at Anwar, and that is when Anwar’s bullet strikes his chest. Only after that his knife plunges into Anwar’s throat. Before he dies, Harris asks Fatimah and Latifah to carry out their mother’s wishes in her will. H

Sets: The set is supposed to be a harbor environment, but we only see a dock and fishing boats, with one time a motor boat coming. The other sets are parts of wooden houses, the beach which is not like a tourist destination, and the interior of the two most important houses in the area. It is never said that the place is a remote or hidden island, but if not, then where did the motor boat come from? This is only make sense if the prison itself is on an island. The place also is somewhat deserted, without any people outdoors except the characters in this title.

Story-enables: What will happen with the conflict between Harris and Anwar? The flashback is Harris taking the blame for Anwar’s act, but there is no intention of Anwar to say thank you. What happens is the opposite, Anwars demands their late mother’s money, and Harris rejects it.

Theme-markers: Anotherflash back, Anwar’s attempt to rape Fatima, makes things bold, like the seizing of Daeng’s goods. The practice of knife-throwing escalates the sense that something will explode.

Emotional-foci: A moment of doubt flashes for a while, before Anwar shoots Harris and Harris’s knife then plunges into Anwar.causing his sudden death—but Harris falling down iss not the emotional moment yet. In the last panel, it is written that the sisters use what they inherit from their late mother to build and organize the orphanage house. This is an emotional relief.

Signification: Poverty in the urban city creates the marginal side of an underworld community, in which the people in this title became characters of the drama. Knowing there are opposite sides, like protagonist and antagonist, also means that there are conflicting ideologies as well. So the underworld is not all black, but a site where the ideological struggle takes place. The tyrant here is Anwar who with his power dominates the area, with getting money as the right goal, whatever it takes, which seems similar to the competition game in urban culture, where criminality is part of the gamble. But even on the antagonist side there are people who fight the dominant one, like Tinah who warns Harris at the last minute, while the protagonist Harris, himself was just part of the gang which followed the code to protect his under age brother. Conflicting ideologies apparently exist even down to the smallest unit.

Poverty in the urban city creates the marginal side of an underworld community.

37. Balada Sebuah Cinta (The Ballad of Love) (96/1980)

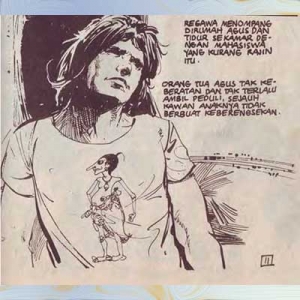

Regawa comes from Ambarawa to Jakarta to be a success. He wants to be a singer, but that is not easy. So for the first months he stays at his friend’s Agus’shouse. Agus has a sister, Asti. Asti’s friend, Mona, loves Regawa’s compositions, and falls in love with him. One day Agus and Asti see Regawa sing with his guitar busking for money. Regawa realizes that, so he thinks it is time to move. ,Kak Budi with his theatre group accommodate him in their workshop. A producer then hears him sing a jingle for advertisement which Kak Budi had asked him to do. From this time on, Regawa’s career rockets. Meanwhile, Mona shares her feelings with Asti, but Asti herself has a feeling for Regawa, which she thinks is not proper as their relationship is like brother and sister. Actually Regawa’s feeling is for Asti, but he thinks that his relationship with Asti should be like brother and sister too, so he builds a relationship with Mona. This triangle cannot be intense anyway, because Regawa as a popular singer is always on tour, and Asti continues her study in Yogyakarta. In the meantime, Mona writes a long letter to Regawa, telling him that her parents are sending her to Ottawa because they do not like her relationship with Regawa. They have arranged for Mona to marry a husband of their choice. Asti who finds out about this later, comes to meet Regawa back stage when he has a show in Yogyakarta. This is the moment when Asti and Regawa know the kind of love they have for each other. H

Sets: The urban dream becomes more a realistic dream, so that the surroundings are not longer always the glamorous metropolitan, but also the workshop, the studios, and the food stalls where Regawa wanders as troubadour. The signs of success are not related to the fashion but achievement, even though there is still an idea of class division in the society, which the signifiers do not show so clear anymore. But there are splashes of space that show conflicting signs, like the garbage spot behind a high building, or a modest stall beside the classier stores.

Story-enablers: When Regawa moves out of Agus parent’s house, his future is in question, more than his romantic prospects, in the context of the background of his desire and goals when he undertook to come to Jakarta.

Theme-markers: The one who attracts Regawa’s attention is Asti, but even Asti feels for Regawa she is emphatically on Mona’s side. This kind of triangle bring the subplot to escalate some tension.

Emotional-foci: After Regawa reads Mona’s letter, Regawa feels his heart tremble, but the content is only clear when he meet sAsti backstage and the tension now is about what they think about each other. The result becomes relief.

Signification: As the romantic relationship is subordinated by Regawa’s struggle to be successful, even though the title is about love, the story is more about Regawa’s trial and error in how to make a living in his way. So the social space is becoming wider than a mere love story. Even before the end panels the story returns to the romance; it is only a subplot for the more realistic urban dream. There is no ideological conflict here, except for the already marginalized idea of a good marriage from Mona’s parents. There is only a competition between a love story and a success story that becomes a hybrid that shows the existence of an urban life.

38. Fajar Menyingsing Juga (The Dawn Also Rises) (46/1994)

Murni, a high school graduate, has to save the family after her widow mother dies. She lives in a poor neighborhood with a younger brother and sister, Amri, still a boy who is a peddler around the area; and Mia who just plays. Her older brother, Toha, is in the army and can only send a small amount of money, which often comes too late to pay the rent. Murni tries hard to find a job, and after many rejections, a service agency office employs her for a very small salary, just enough for her transport and lunch. Apparently her boss is attracted to her, and tries to buy her with expensive goods and even a house. Pak Rachmad, her neighbor who has replaced her parents, advises her quit that agency and back to her old job working in a laundry. One day Mia is sick and Murni does not know what to do because she does not have any money. But Amri with his one year savinsg solves the problem. Then comes another problem., When they take Mia out, there is heavy rain. Fortunately, a luxurious car stops in front of them, and offers them a lift. At the hospital, the driver stays, and after Mia is examined by doctor, he drives them home, and comes inside their poor house. His name is Danny, and Murni has a good impression of him. Day after day they meet again. One day, Amri who is peddling near a construction project sees Danny working there as the boss, and Danny sees Amri too. He gives Amri so much money that Murni, because of her previous experience, feels she has to ask what Danny’s intentions are. Danny says his intention is only that he cannot see the woman who has affected him so much working in a laundry. This is exactly what she expected from him. So, now Pak Rachmad interviews Danny about his further intentions, like marriage, and warns Danny that there will be obstacles from his family, because of the social class issue. This is really what happens, Bu Brata, Danny’s mother, asks Danny about his marriage plans, meaning when he will marry Dinah, the rich girl of Danny’s mother’s choice. Danny answers that he already has his choice. Then Dinah meets Danny at the office, which Danny does not like, and when Dinah asks about their relationship, Danny says that he already has a choice. Angrily Dinah leaves the office. Curiosity makes her check up on Danny. Her investigation reveals that everybody in the neighborhood understands Danny is Murni’s boyfriend. Dinah reports this to Bu Brata. Bu Brata and Dinah come to Murni’s house, find her, and say that Danny is already engaged to Dinah. Of course Murni is disappointed, and thinks that Danny is just another liar that wants to trap her. Meanwhile, Bu Brata, drowned in her anger, crosses the street in front of the neighborhood without noticing a speeding car which hits her. Forgetting about her broken heart, Murni with an agile act takes care of Bu Brata, and with Dinah’s car rushes to the hospital. It turns out that a special type of blood is needed at the moment to save Bu Brata’s life, and Murni’s blood type is the same and she is willing to give it without hesitation. After coming home, she still thinks that Danny will come soon, but Danny only comes on the seventh day when she cannot take it anymore. They fight for a while before Danny explains that he did not get engaged to Dinah, and how he knows that Murni saved his mother. After three days in the intensive care unit, then hearing his mother story, it took time for him to face Murni. Then they go the hospital together, and Danny introduces Murni to Bu Brata as her future daughter-in-law. H

Sets: The poor neighborhood in this title has nothing to do with criminality. The panel of woven bamboo and wire netting as the window instead of glass show the class of the community that live there. The typical urban scenery at the beginning, changes to the interiors of the wealthy homes and offices as a contrast to Murni’s neighborhood shown with a kind of consideration. The construction project nearby makes the encounter of Murni and Danny realistic besides also signifying the ever growing urban environment.

Story-enablers: When Murni meets Danny, Murni’s miserable past becomes like a flashback that enables a push in the story with expectation of Murni’s better future.

Theme-markers: Bu Brata first, and then Dinah, became obstacles that threaten the future of Danny and Murni. Step by step shown with the Dinah’s checking of Danny, the report to Danny’s mother, and the act of coming to Murni’s house.

Emotional-foci: The story of the past ends abruptly changing with the accident. Now the focus is on Murni’s efficiency and humanity, like being the blood donor, besides what she actually feels at that moment. Her disappointment that Danny comes so late, and the relief, still work even though from the beginning we are already told that this is like a Cinderella love story.

Signification: The issue of course is class division. From the start the poor neighborhood is shown as a very different scene from the urban dream, but realistically part of the existing urban culture. Social division is like destiny, because the unfair social economic construction then determines the social hierarchy of birth. Bu Brata thinks that she cannot deny the existence of Murni, not only because Murni from the first second after the accident helps her, but because in her blood flows “the blood of ordinary people”, which means her blood is now not fully “aristocratic blood”. Even though in the late cosmopolitanism this kind of division should be a kind of joke, in this title it is taken seriously as a reality—and it seems like there is nothing like an ideology to challenge it.

2. THE FINDINGS AND GENERAL ANALYSIS

After an examination of each title from 38 romance comics created by Jan Mintaraga as the data corpus, I will note the characteristics of the narrative, classify the types in the genre, and then define the urban representation of the ideological struggle as a general analysis of the findings.

2.1. The Characteristics of Jan Mintaraga’s Romance Comics

2.1.1 The Political Space: How Sets Speak

First, the sets can be divided according to how space is used. There are exteriors and interiors. Then the exteriors can be divided again into exteriors in the city and exteriors in the country outside the city.

1. Exterior in the city.

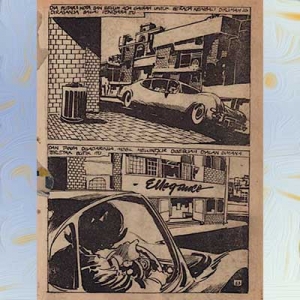

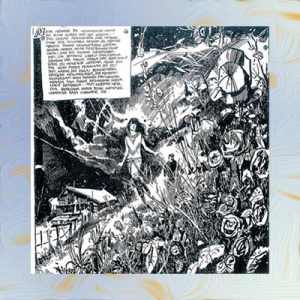

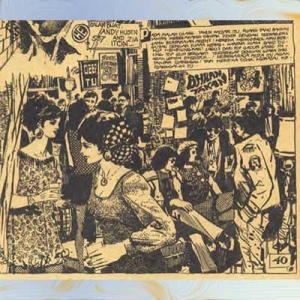

a. The most recognizable are panoramic metropolitan exteriors that try to represent a glamorous neon jungle with the name plates of the stores or advertisement billboards, conveying the business district, often with a clean and proper paved streets with luxurious cars passing by.

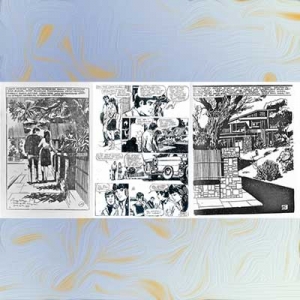

b. The outdoors of housing complexes where couples walk together under the moon to share and enjoy their feelings, with modern architecture houses as the background. These houses are intended for the middle or even high-class society.

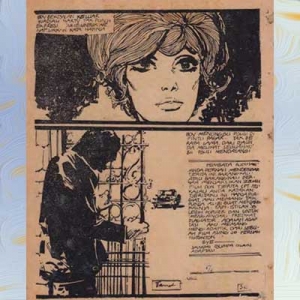

To make the image as the place of happiness that is never a reality.

c. Destinations for romantic couples, as the counterpart of cinemas and restaurants, are parks which seem very clean with designated chairs, gardens, and narrow paths, to make the image as the place of happiness that is never a reality.

Experiencing the depths of his suffering in dark places.

d. Places where the male broken-hearted lover walks and wanders around, experiencing the depths of his suffering in dark places of alleys, slums, and no-man’s-land where the underworld life goes on with its own drama. But as the opposite of the civilized buildings, places that convey the uncivilized part of the world sometimes show a very proper garbage can, which according to the style probably did not exist at the time. As another alternative, the broken-hearted male or the character in doubt goes to a place of serenity, inside or outside town, and meditates under the moon.

2. Exterior in the country

The country is part of the urban space.

The exterior in the country is still a setting for city people. It means that the country is part of the urban space, at least as part of the outdoors as the stage for the extension of the indoor problems. So the mountain scenery, beaches, or the exteriors of villas in the country are sometimes only the alternative of the outdoors destinations of the city; but at other times are the whole set of the entire drama from the beginning to the end.

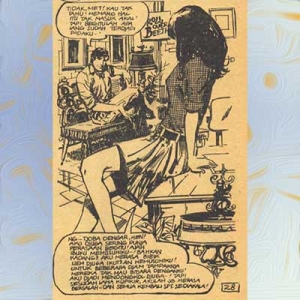

3. Interior design: Representation of social class

Indoors romance activity most of the time takes place inside private houses, for instance when the lover boy comes to the house of the girl, then the girl thinks about him in her room, which shows that the actor is from certain class, and as that class is intended to be middle or high class society, which is conveyed by the interior design.

There is iconographical presentation which can reflect the urban culture.

So in the interior of a house there is iconographical presentation which can reflect the urban culture as architectural design, style of the furniture, wall decoration, and images, or even messages that came with words on the posters, types of paintings, in short any decoration inside the building. This approach also happens to describe offices and other functions in social activities like night clubs, restaurants, or club houses. When the plot involves the low class or the underworld, the same treatment and methods on ways the signs are used to deliver messages and nuances occurs.

2.1.2. In The Room of Her Own: Main Female Characters

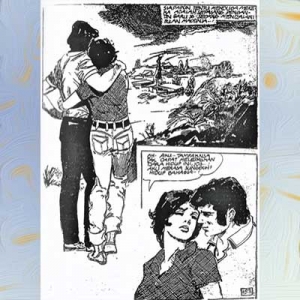

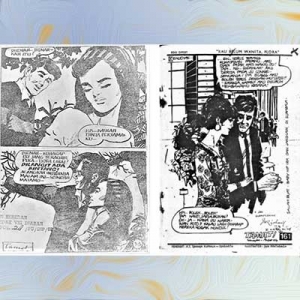

The female character is always shown in a fashionable way.

Generally all Indonesian romance comics. Mintaraga included. at the peak of their popularity in the 1970s always used two panels, upper and lower on each page,. But in Mintaraga’s works, there is always a display of the female main characters in one page, showing everything needed to identify an interpretation of the urban culture. The female character is always shown in a fashionable way, like a pose of a model for the fashion photographer, with the latest up to date fashion design of the time, if it was not from actuality could be from the media. This main character is always shown as beautiful as possible in the dominant fashion, especially her clothing, supported by the interior design that shows the signs of the time.

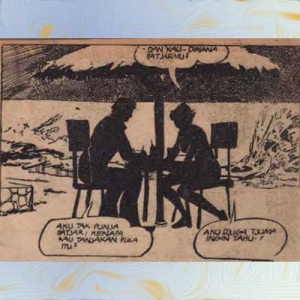

2.1.3. Jacket, Jeans, T-Shirt, Sneakers, Cigarette in a Somber Mood

: Main Male Characters.

Athletic figure, somber expression.

Drowned in depression, cigarette in his mouth.

A scene of frustration, never out of style.

Sneakers …

The male main character, always depicted with quite an athletic figure, when drowned in depression, is alone with or without his thoughts in a somber expression. Even though this is intended to be a scene of frustration when the character’s self confidence is in question, it is never out of style. So he wears a t-shirt covered with jacket, jeans that are sometime folded on the bottom, and a cigarette in his mouth.

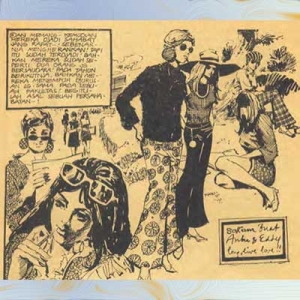

2.1.4. The Fashionable Life Style of the Seventies

As though modernity is a kind of set of symbols and not an attitude.

In romance comics, the life style should support the drama that is the subject of the narrative. The image of “modern” for instance, is not about how people think, but how they behave: it is more about what people wear and ride, where they stay and where they go, as though modernity is a kind of set of symbols and not an attitude.

The life style should support the drama that is the subject of the narrative.

Added to the exteriors and interiors already mentioned, besides fashionable clothing or sport cars, is also the language, which uses one or two English words in the Jakarta popular language of the youth, to show it as an urban phenomenon. Included in the language is not only how the youngsters speak, but also what is written on the posters in the room, billboards on the streets, and so on. While in the general life style, the subculture of the youth in conflict within the old generation’s point of view became the important signs.

2.1.5. Notes on the Plots

From 38 romance comic titles there are 23 titles where the plot has a happy ending, 11 titles with unhappy ending, 1 title between happy and unhappy, 2 titles with an open ending, and 1 title between unhappy and open ending. tThese notes are on the plot, not the ending but the values that determined the choice of ending. A consideration of the kind of values can show the power and ideology in discourse of the time.

-

- The Road to Happiness: There are many obstacles for a young couple to unite, if not from a competitor, then from the power of the older generation, like their parents who have a different way of seeing the world that is called ideology. In the case of competition, often this also involves the choice of values, not really about feeling or heart. Or, to be precise, the feeling of love is constructed by the existence of the discourse. It should be noted here that competitors or parents were only two of many plot alternatives. What matters is that happiness in the end, becomes the celebration of which group in the society wins in the ideological struggle for power.

- The Socially Constructed Fates of Unhappy Endings: Like the determinant factors that construct the happy endings, the same thing happens with unhappy endings. So here it is more interesting to examine who lost in the struggle for love and why, in regard to the values. In some cases, often the losers looked as though they were already on the wrong side, and easily open to be blamed. In other cases, the drama do not have any good sides, as it is in a dark mood, or the main character’s degree of self pity is too high, which makes him or her blame themselves in a fatalistic fashion.

- Ambiguity and Open Endings: The ambiguous ending is like an open ending, but an open ending should not be ambiguous but show possibilities, like life itself when any prediction comes to nothing. There are two kinds of ambiguity here: between happy and unhappy and between unhappy and open ending. The first is an irony of tears, is that the tears of happiness or the tears for someone else’s unhappiness (Between Two Eves); second, while the story ends with an unhappy outcome, as though finishing with a closed ending, the last sentence informs the reader about a fact that opens the story again (Back from The Hills). This open ending is similar to the former open ending, which remains openly to another new plot (Egg at the Top of A Horn), while the other is open only because the story is not yet finished (Tembok/ Wall). However, all these endings show the power in play for the final say.

- The Road to Happiness: There are many obstacles for a young couple to unite, if not from a competitor, then from the power of the older generation, like their parents who have a different way of seeing the world that is called ideology. In the case of competition, often this also involves the choice of values, not really about feeling or heart. Or, to be precise, the feeling of love is constructed by the existence of the discourse. It should be noted here that competitors or parents were only two of many plot alternatives. What matters is that happiness in the end, becomes the celebration of which group in the society wins in the ideological struggle for power.

2.1.6. Discourses of Values

Values are things believed and trusted without question, as taken for granted, that became the basic factor in the construction of the plot. As values are part of the discourse, the dominant values are always put into question and resisted. This also means that the values which determine the plot also develope. Here are the discourses:

-

- Identical twins, physical similarities between sisters, or even people unrelated become a reason for the case in a relationship like in The Sinking of the Ship Bendana (1966) and Wait for Me at The Gate of Eden (1966).

- The act of suicide, successful or not, often is a choice as a way of out of a problem, in love or anything else.

- Without suicide, failure in love still can kill someone.

- Love triangles are more the male with two females, or more, then one female with two or more males.

- Parents, although their position is always important as the representation of power, are not always given a name, and when there is a name for the father, the mother only use her husband’s name. It is very rare that a mother uses her own name.

The successful characters at the same time are losers in love.

- Success or not is a significant factor, as a student, artist, or businessman. The plot plays with these positions, for a kind of tragedy, when failure in career happens to be a failure in love as well; while for a kind of irony the successful characters at the same time are losers in love.

- There is never a big family, two children are the maximum, usually only one, and when there are three, as in The Damned House (1971), the first one happens to be the father’s mistress.

True love should be in a proper place.

- True love should be in a proper place. Characters who love and are loved in the wrong time and wrong place, like between a different social class, will never survive.

Because she is a woman ….

- Gender issues: All the female main characters are feminine but the roles are always active whether as student or working woman. But, as to how a man sees them, in Melody at The End of the Year (1967) the male character rejects his girlfriend’s offer to help because she is a woman, while in After the Storm (1971) the working women rely on their looks and the good-always-waiting wife stays at home.

She has virtually no important authority in the house or in her children’s life, even her name is never mentioned.

For older women, in the position of a mother, when she has a husband she has virtually no important authority in the house or in her children’s life, even her name is never mentioned. However, when the mother character is a widow, or lives alone, her authority is a threat to her children’s relationship (see also notes No.5). Also there is a division on the fields of work for women, that can classify a woman of being a good woman or bad woman, and these kind of values influence the plot if for instance a good woman is forced to work in a bad woman’s field of work, like in I’m Not for You (1967) or A Tyranny Shatered (1979 [1969]).

The plots are not always about romantic feelings but ‘who owns who’.

- Relationships as the political drama. The word ‘political’ means that the relationships between the actors in the plots are not always about romantic feelings but ‘who owns who’, as the competition of lovers involves other people with their own interests outside the romantic relationships. The conflict of values as the drama also means the conflict of ideology, making the discourse that constructs the relationship problems a political site.

2.2. Types of Romance Comics

The themes of Mintaraga’s romance comics change over three decades, from naïve romance where relationships become the most important thing in the life of the young characters, to realistic romance as part of a dramatic story with more mature characters, where in some cases love becomes just part of a bigger game like power. So, at one time, there is a hegemonic process where sometimes a hybrid creation takes the romance away, while at another time it is as though the original genre pulls it back. From these 38 titles the classification can be as follows:

2.2.1. True Romance

This already existed as a genre usually called romance comics, where the theme and the plot deals only with the success or not of relationships, with obstacles like the existence of a competitor, the power of parents, sickness, or a bad fate like an accident. Social class differences are one of the popular issues that contribute to the drama. With a happy, unhappy, or open ending, 35 of the titles thematically were in the genre of true romance. However, even in the same genre, there are not only variations of the plot for the same theme, but also a deepening of the theme until the human relations of the drama turn out to become dark and gloomy beyond imagination, like in the title The Damned House (1971), which seems to try to push the morality game to the limit.

2.2.2. Hybrid Romance

Any difference from the stereotype within a genre, even if only a little, is always important because it reflects the process of cultural hegemony, the place of negotiation and opposition that revitalizes culture. In the romance comic genre, some splint as a hybrid process with another genre, or even become something entirely new. From these titles, The Teenagers Incident (1966) seems to be very different to the others. At the beginning it seems as though the romance is hybrid with crime story genre, but then there is a shift to a story of heroism which is related to the political situation at the time. So actually this is a hybrid of not only two but three genres from the comic culture. For the years to come until now this title contributes as an artefact for an examination of history. For other hybrid titles, Among The Wolves (1971) and A Tyranny Shattered (1979 [1969]) clearly show the hybrid of romance comics with crime stories.

2.3. The Urban Representation of Ideological Struggle

These romance comic books represent the urban in the way that they are signs that have meaning from the combination of pictures and words. The process of signification that the findings detect reveal a shift from the naïve romantic relationship in an idealistic world to the more realistic sets as a stage for the realistic relationship. This shift is the result of the hegemonic process of representation of the urban culture, which actually is a process of influencing each other inside the discourse. Here are some excerpts from an interview with Mintaraga:

Could you tell about the character’s attributes in your comics, like rolled jeans, jackets or pullovers and sneakers?

“The youngsters’ way of life at the time was actually influenced by what I depicted. But that’s nothing new. I spend my money to buy records, so that there are practically no Western singers I don’t know. It’s from record covers that I transfer the style of dress to my comics, and that was accepted by the youngsters. Actually they could take this directly from the records themselves, but the fact is they took it from my comics.”

Your comics maybe filled a gap in the scarcity of music and fashion magazines at the time?

“That’s not what I meant. It’s because there was a vacuum in other sectors.. American films were few. There were a lot of spaghetti westerns from Italy. Only music was relatively fluid. There were many private radio stations, illegal amateur stations. But recordings were still rare, and records were still expensive. Maybe my comics filled the gaps. Even the popularity of musicians could not compete with me. Alfian received 2-3 letters a day, I received 50, from all over Indonesia.” (Rentjoko, 1992: 33)

So in the beginning, the way the youngsters wear certain clothes, the house architecture and surroundings, interior design, and even the way people talk existed only in Mintaraga’s comics before they became the real trend that in turn influenced the comics. But at that same time Mintaraga already faced and was living inside an urban reality that made his romance comics in all aspects not as dreamy as before.

The signs in those shifts represent the hegemonic process in the urban city as well, while the process is the game of incorporation and resistance, where the subordinatent group resists the discourse of the dominant group, and the dominant group negotiates the discourse of the subordinate group. As these are represented in the narrative of Mintaraga’s romance comics, the findings are further examined to present the meaning.

The ideology is called love, as this is actually an abstract concept in the concrete world of picture and words, which tries to represent an urban world as the stage of people with their romantic relationships that are not free from the conscious or unconscious interests related to the existence of power, discourse, or identity politics. In this hegemony process of relationships, there is always the nexus of textual representation like the signs from the surroundings, what people wear, how people pose, behave, move, and talk. The visual and written languages send messages that span chronologically from 1966 to 1971, so that after the brief survey the data corpus means something of the urban development.

2.3.1. The Visual Atmosphere as Urban Culture Sites

As the buildings in the city also function as social space, all the dominant signs try to show the urban city in the modern fashion, from the architecture, part of the city plan, to the brands on the signs in the business district that are dominated by foreign names from Western culture. The housing complexes of the elite, the exterior and the interior design, also room decorations, are full with orientation of the established modern culture. Included in these phenomena are anything worn or ridden in the mood which also shows a dream or imagination of the future, and this future is like a modern big city world.

This is what is shown in most of the titles from 1966 to 1969, when Jakarta had already started the New Order period, but had not really developed or changed at a time when the Soeharto regime was still busy treating political issues and just begun to invite foreign investment. But in one of the creations from 1969 the signs seems to be making a joke on the Western-like imagination, when readers see local movie titles and local names on the billboards.

From the 1960s to the 1970s development began, and Jakarta as the concentration of government administration and business activity in a way changed the face of the city. However, even though Jakarta is always mentioned as a metropolitan city, at the time it was still only a big village. In 1969, the Indonesian pioneer of cinema, Usmar Ismail, created a satirical film of that cultural stage with the film Big Village, the story of a big city with the provincial attitude of the citizens.

This kind of antithesis is also represented in Mintaraga’s romance comics, when the scenery shows not only the ideals of the modern atmosphere but also the other side, like the dark places that seem untouched by modernization which actually were caused by the structural injustice of development, which created marginalized communities together with their own social space.

In the name of modernization, the unbalanced economical distribution not only createed class differences with all the socio-political consequences in the society, but also subordinated the signs of traditional culture, making this seem natural in an urban media representation of the big city.

As an example, note that traditional clothes like kain-kebaya are only present as what the mother wears, especially mother characters that do not have any importance, or it is not a surprise if worn by house maids as well, while if the mother’s role is the opposite she wears Western-style dress like a skirt.

Peci is always used to portray people from the subordinated group.

The peci (rimless cap) that is also an icon of national identity is always used to portray people from the subordinated group like drivers or stallkeepers.

Traditional design on modern clothes.

On some occasions in a 1980s work, the subordinated group resists while the dominant negotiates it, as represented with traditional design on modern clothes.

2.3.2. Love in The Time of Urban: The Written Language

The comment and dialogue in the comic’s balloons are a written language that in a limited space aim to effectively deliver the thought. As written over the decades, there are transitions, beginning from quite proper Indonesian language in the dialogue that is not found on the street, until reaching a style of the Jakarta’s youth language, which in a way adapts what is spoken in real life but at the time time, because of the popularity of the comics, influences that style as well.

This language tried to adapt, follow, and anticipate the development of the younth sub-culture language, meaning that it is very possible it had not been heard before. Intended as a spoken language, but in a written form, makes the process like a refinement of ideas that come to be read better, just like the development of the urban culture that seems wild at beginning and becomes more orderly, without eliminating the conflict in the hegemony process.

Reading all the titles chronologically, one can follow from the language in the beginning the idea of love as a single entity that is holy, and absolutely exclusive between the romantic couple as though they live in their own world. Only later when the plots occasionally begin to involve a wider context, social aspects like class differences, does the romance drama became more meaningful than merely rivalries in a love triangle. Class differences in most of the plots come from family, that sees blood legacy, or wealth, with the family or not, as consideration for survival.

In most of the cases these two combined. These factors really matter, more than the matter of love, which creates the dramatic conflict that comes from the source: the ideological struggle of two competitors, idealistic love versus realistic life. As far as the ending is concerned, the happy or unhappy ending usually comes as a result of choosing idealistic love. But of more importance to the urban issue is the fact that the competitor of idealistic love, namely real life, arrives together with urban cultural development itself.

Over the 1970s, in some of the plots the possibility arises for this idea of holy love to be contested, not as romantic relationships that are easily broken through the challenges of real life, but by compromised love. That is when wealth, and not the person who owns it, becomes another competitor which can be joined without losing the love for someone else. The morality in question, that love liberates one from the obligation to be good and have an adventurous affair, not only comes from the dark side of the society, but also happens in high class and respectable families.

This matter of wealth intrudes into romantic relationships in a bad way because wealth is represented by a life style that needs to be supported by money, while the issue of blood inheritance as an old world issue is still present in the mix with the meaning of wealth. It’s possible that a person from an aristocratic family can become a maid when she has lost everything, but with or without the blood, the wealthy family is always represented as high society. The meaning of wealth in the practically material world decides the fate of romantic relationships, for better or worse, in the urban city.

What is important here is that the comment in the comics, which comes from the narrator, decides what is morally right or wrong at the end of the plot, and most of the time does not side with the wrong one, even though the narrative seems to sympathize with the wrong characters.

The crucial moment between 1966 to 1971 in romantic life in Jakarta as represented in Mintaraga’s comics is shown as the period of critical change, that settles the new compromise equilibrium, as can be examined later from the 1980 and 1994 titles, which show how even with everything always changing in the developing urban city, some old values or ways of life just never die.

6. The Urban Culture as Experimental Culture: The Rise of the Life-Aesthetes

From the evaluation above it can be seen that the urban city as a text shows the contestation of ideology, in how the discourses develop and change values, in love or wealth, that also means change the people. This change is not an elimination of the old and replacement with the new, as in the hegemony process there is a negotiation, which implies the holding together of opposite sides in an ongoing process of give-and-take. As a model of meaning production, negotiation conceives cultural exchange as the intersection of processes of production and reception, in which overlapping but non-matching determinations operate (Gledhill, 1988: 68).In this meaning the urban city of Jakarta, as represented in Mintaraga’s romance comics, became the site that showed how the culture works. Material culture developed with its own speed, as the impact of industrial capitalism, but the cultural aspect of the city, in term of questions of class, family life, life style, and ethnicity, in the heterogeneity of the society, did not move, flow, or develop at the same speed or even in the same direction. As the friction or point of contact occurs between all aspects in the city, it needs time to find kinds of specific identities in the multiple significations of the romance comics as a cultural commodity.

Thus some time after the New Order took over power from Soekarno who said “Go to hell with your aid” to Western capitalist countries, and the New Order opened the country to foreign investment, the political economy of development not only changed the financial opportunities of the people in terms of prosperity, but their orientation of life as well. So the change in political economy brought the society to, what Ulrich Beck has called ‘the condition of an experimental culture, where values become more differentiated, and personal autonomy self-evident and inescapable, which also means that cultural sources have emerged for the joyful and creative taking of risks, when the individuals in the urban society become the only seemingly egoistic “life-aesthetes”.’ (Beck, 2000: 147-8)

The concept of life-aesthetes comes from an outlook of the 1989 generation in Germany after the collapse of Berlin Wall going through the 1990s, which Johannes Goebel and Christoph Clermont described as the virtue of disorientation. This concept in some way helps to describe the experimental culture in the urban Jakarta of 1966-1971. This life-aesthete, Goebel and Clermont say, is like …

…. the knights of neomodernity [who] hold sway over a realm that contains no more than one person, yet the means of shaping this dominion are potentially limitless. Their round table is globally networked, their palaces can take in whole continents.

For the life-aesthete economics no longer has anything to do with the earning of money: he sees it as a much more inclusive model of processes of calculation and negotiation, which is always necessary when he comes into contact with other aristocrats, while the aristocratic existence is pre-economic. Economics is the foreign trade of principality that is otherwise governed according to the irrational principles of the divine right of lifestyle aesthetics. / The new morality of the life-aesthete uncomprehendingly confused with a collapse of values and egoistic opportunism (Goebel & Clermont, 1997: 22 in Beck ibid., 148-9)

So the social intercourse of the life-aesthete can set the direction of the next generation’s style, as the civilization laboratory of everyday life. The life-aesthetes also constantly arrange their lifestyles autonomously and shape and stage both themselves or their own life as an aesthetic product. Whenever they live, think, and produce they are in a direct relation between work for themselves and work for anybody else, the market as the result does not have mass character but niches or mini-markets.

As Beck explains, ‘The niche-markets phenomena is one of the main responses to the end of two important features of modernity: mass production and full employment. Niche culture and production maybe could present the counter-model to rationalization mania that were be spread evenly on big capital. So niche production options are (a) makes possible a cultural laboratory of the future and an inventive mode of production, (b) does this with low cost production costs, and by relying upon independent initiatives which (c) presuppose and strengthen regional specificities and the trans-national of civil society.

So niche production options are (a) makes possible a cultural laboratory of the future and an inventive mode of production, (b) does this with low cost production costs, and by relying upon independent initiatives which (c) presuppose and strengthen regional specificities and the trans-national of civil society.

This runs completely counter to the know-all approach of adults defending the old values and world order. Their aim in this is to burn up the cultural riches of life- the world of creativity which the ‘the gentle young’ represent and produce, and no doubt it would indeed exhaust and exclude the the key milieu from the self-renewal contemporary society.’ (Beck, 2000: 149-50).

The crucial period of 1966-1971, as represented by Mintaraga’s romance comics in urban Jakarta, give us ways to understand the existence of an experimental culture, which is useful to reflect on now, at another crucial period of entering the ever changing digital age of the future. The role of the comic-book market as the niche-market that opens possibilities not only as an alternative market, but as an alternative culture, which the romance comics as both a commodity and a creation of art functioned already as a cultural laboratory of a crucial period of urban Jakarta, which can always be read again to compare with the big changes of today.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ajidarma, Seno Gumira. “Jan, Roman, Zaman”, TEMPO weekly magazine, December 26th, 1999.

Appadurai, Arjun. “Disjuncture and Difference in The Global Cultural Economy” in Simon During (ed.), The Cultural Studies Reader, Second Edition. London and New York, Routledge: 1999.

Atmowiloto, Arswendo. “Komik Itu Baik (2): Koran Medan, Serta Cinta Jakarta”, Kompas daily, August 11th, 1979: i-x).

Barker, Chris. The SAGE Dictionary of Cultural Studies. London, SAGE Publications: 2004.

Barker, Martin. Comics: Ideology, Power & The Critics. Manchester, Manchester University: 1989.

Barson, Michael. Agonizing Love: The Golden Era of Romance Comics. New York, Harper Collins: 2011.

Beck, Ulrich. What is Globalization? Translated by Patrick Camiller. Cambridge, Polity Press: 2000.

Bonneff, Marcel. Komik Indonesia. Translated by Rahayu S. Hidayat. Jakarta, Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia: 1998.

Kleden, Ignas. “Social Science & Humanities in Indonesia: Making Sense of the Experiences with Globalization and Capitalizing on Best Practices”, paper for International Seminar on “Social Science and Humanities in Light of the Challenges of a Globalized World”, Ruteng, November 18-20, 2017.

Lubis, Firman. Jakarta 1970-an: Kenangan Sebagai Dosen. Jakarta, Penerbit Ruas: 2010.

Mintaraga, Jan. “Dalam Negara Modern, Komik Mutlak Ada”, Eres comic magazine, No. 8, June, 1970.

——————- “Komik, Bastar Tanpa Kewarganegaraan”, Kompas daily, May 9th, 1983.

Mulhern, Francis. Culture/Metaculture. London and New York, Routledge: 2000.

O’ Sullivan, Tim., et.al. Cultural and Communication Studies: Key Concepts. London and New York, Routledge: 1994.

Rentjoko, Antyo. “Jan Mintaraga: Komik adalah Warung Tegal”, Jakarta Jakarta weekly magazine, No. 327, October 3-9th, 1992.

Soekarno. “Penemuan Kembali Revolusi Kita”, http://primbondonit.blogspot.com/2011/11/arsip-nasional-pidato-bung-karno-hut- ri.html. Accesed on November 25th, 2012.

Soelin, M.S. “Jan Mintaraga pelukis Tjergam ‘Sebuah Noda Hitam’”, Eres comic magazine, No. 6, February, 1970.

Sabin, Roger. Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art. London, Phaidon: 1996.

Storey, John. Cultural Studies & The Study of Popular Culture: Theories and Methods.mEdinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996.

—————- Inventing Popular Culture: From Folklore to Globalization. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing: 2007.

THE END

*Seno Gumira Ajidarma. Partikelir di Jakarta.