Picture-Story in Circuit of Culture: The Politics of Adaptations

Oleh Seno Gumira Ajidarma*

Kali pertama dimuat borobudurwriters.id. Terjemahan bahasa Indonesia akan tergabung dalam Dari Spider-Man sampai Wayang: Komik dalam Kajian Budaya (2025).

Abstract

An artefact of an assignment behind the cover of the picture-story Mummy (1968) opens ways on how it is adapted to Afterlife Man (1970) and, in turn, on how it was adapted from the source, Mummy (1962). After adapting Mummy in 1968, the artist went on to other works of adaptation from the Western comic genre to an intended Javanese martial arts comic genre in the same year.

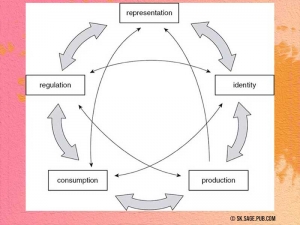

This survey investigates those adaptations as cultural processes with the concept of the circuit of culture by Stuart Hall, which is constituted by five interacting elements: the moments of representation, identity, production, consumption, and regulation, to show how culture is being transpired.

Investigation of representations from traces in cultural processes reveals political or ideological manipulation and disguise, consciously or unconsciously, in the history of adaptations that construct the contemporary world today.

Keywords: adaptation, comparation, cultural process

1. From Fidelity to Re-Creation in Adaptations: Background

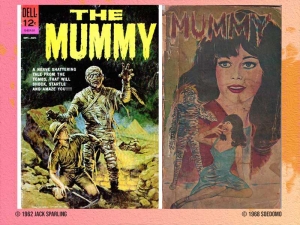

The picture-story Mummy was distributed as the work of Jack Sparling and others, while the painted cover was unfortunately credited later only by an unknown artist as the No. 211 issue in the September–November 1962 edition of Dell’s Movie Classics comic books. This comic book itself is credited as inspired by the classic Universal Monster, The Mummy.

In the discourse of adaptation theory, this kind of object is part of research materials where adaptation studies came to the third wave in the 1980s, called adaptation industry, with the increasing evidence of adaptation’s print-based ‘afterlife’ in the form of ‘tie-in’ editions, novelizations, published screenplays, ‘making-off’ books, and companion titles becoming incontestable (Murray 2008, 9).

While the first wave of adaptation studies in the 1950s concentrated on fidelity criticism and the second wave from the late 1970s concentrated on isolating the signifying codes, the third wave opened adaptation studies to concepts of audience agency, which developed in the 1980s and 1990s, where adaptations interrogated the political and ideological underpinnings of their source texts, translating works across cultural, gender, racial, and sexual boundaries to secure cultural space for marginalized discourses (Murray 2008, 6).

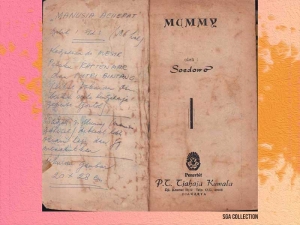

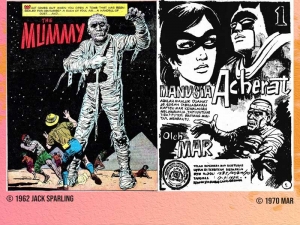

Mummy, the picture-story, from 1962 in the United States to 1968 in Indonesia.

In the year 1968, the comic book Mummy by Soedomo was published in Jakarta as an adaptation, which happened to be faithful to Mummy (1962), with slight differences, both as technical and cultural adaptations. In this case, fidelity or faithfulness related to the understanding of fandom in the adaptation culture, where the activity of fans in relation to cult texts, reminds us that these readers and viewers automatically set themselves up as critics who feel that part of their activity is best expressed in a rewriting or reframing of the ‘original’ (Whelehan in Cartmel, Whelehan 1999, 16).

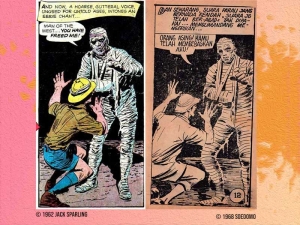

This Mummy (1968) by Soedomo, especially the visual image and the character of the mummy, would then inspire the making of Afterlife Man by Mar in 1970, where the creature of the mummy became the antagonist as opposed to Kapten Mar, the superhero from the serial, which obviously was adapted from DC’s superhero Batman.

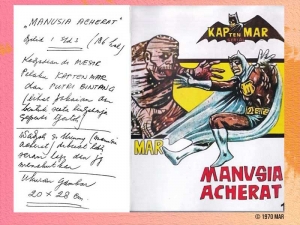

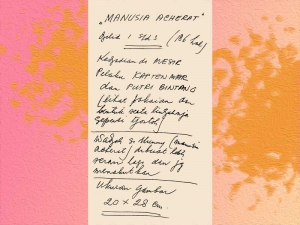

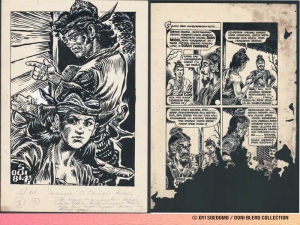

The original artefact of the assignment to create The Afterlife Man based on Mummy by Soedomo.

The artefact (left) that showed the description of how Afterlife Man (right) should be made, included the specificity on how to make the mummy for their own interest.

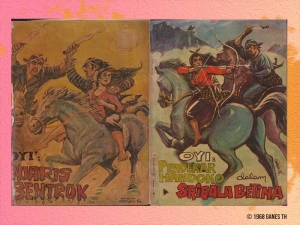

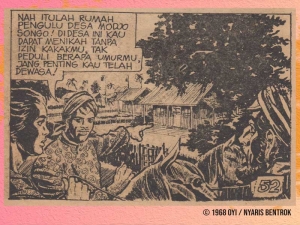

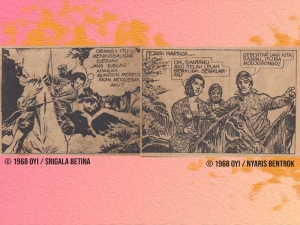

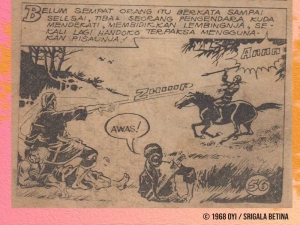

Then, Soedomo, who now renamed himself ‘Oyi’, published other picture-stories, Almost Clashed (Nyaris Bentrok) and She-Wolf (Serigala Betina), both in 1968 and adapted from the genre of Western comics, that progressed from a faithful standpoint to a visual re-creation, which seems like a full circle of the circuit of culture completed. This is the main working concept of this brief survey, not from the adaptation industry but from the concept of the circuit of culture.

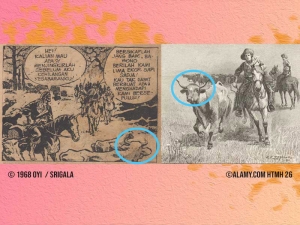

The 1968 producer’s thougt: the front cover of Oyi’s comic books made by Ganes Th, because the commercial success already proven. Horses are dominant in these covers as were refer to the genre of Western comics.

2. Similarities and Differentiation: The Case

The case of this preliminary survey is that while Mummy (1968) faced Mummy (1962) in the making, and the latter became dominant (even the slightest subversion is going to be meaningful); this Mummy (1968) inspired and developed the mummy character in Afterlife Man (1970). These phenomena generate the meaning, not of similarities, but of differences on the reader-creator position, in the politics of adaptation to constitute an identity, however marginal the space is. Hence, the questions are: (1) how is the making of differentiations going on?; and (2) what is the meaning of differences made by the creators, in their contemporary circumstances and the cultural context, as the politics of adaptation? It does not necessarily mean that similarities exist without signification.

3. Circuit of Culture: The Concepts

Circuit of culture, which is constituted by key ‘moments’ and Stuart Hall’s concept of cultural processes, provides an analytical framework to view artefacts of picture-story that is also known as comic-book. The circuit of five interacting elements are the moments of representation, identity, production, consumption, and regulation, which show how culture takes place in the world.

It does not much matter where on the circuit an analysis stars, as the surveyor had to go the whole way round before the analysis arrives at the conclusion. As these parts of the circuit are separated into sections, in the real world, these sections overlap in a contingent and complex way (du Gay, Hall et al. 1997, 3-4).

3.1. Representation

As part of the circuit of culture and the central practices that produce culture, a representational system operated in how, through language as a medium, human beings make sense of things so that the produced and exchanged meaning could be shared among them. This makes language the key repository of cultural values and meaning.

Language, whether as written words, sounds, visual images, musical notes, or objects, stands for or represents to other people the producer’s concepts, ideas, and feelings. Representation through language is central to the production process of meaning. The investigation of the survey material will follow the traces of these meanings to reveal the cultural process.

Cultural is not so much a set of things, in this case, the picture-story, but a process of the production and exchange of meanings between the members of society or group (Hall 1997, 2).

3.2. Identity

Identity has been seen as conceptually important in offering explanations of social and cultural changes. Identity is most clearly defined by difference, that is, by what it is not. Identity offers a particular focus on a ‘moment’ in the circuit of culture as produced, consumed, and regulated within culture, creating meanings through symbolic systems of representations about the identity positions that might have been adopted. The positions taken up and identified constitute these identities.

Identities are forged through the marking of difference, which takes place both through the symbolic systems of representation and forms of social exclusion. Identity is not the opposite of, but depends on, differences.

A cultural artifact, such as a comic-book, has an impact on the regulation of social life through the ways in which it is represented, the identities associated with it, and the articulation of its production and consumption.

Identities and artifact that are associated and produced, both technically and culturally, in order to target the consumers who buy the product with which they identify (Woodward 1997, 1-14).

3.3. Production

Meaning is produced at economic sites and circulated through economic processes and practices, no less than in other domains of existence in modern societies. It is relevant to treat economic processes and practices as cultural phenomena, depending on meaning for their effective operation. Economics can be seen as a cultural phenomenon because it works through language and representation.

Processes of production and systems of organization can be seen to be more than simply objective structures that people inhabit and reproduce. Through a cultural lens, they become assemblages of meaningful practices that construct certain ways for people to conceive and conduct themselves at work, where they have sought to create new meanings and thus to construct new forms of work-based identity.

In so doing, they have indicated precisely how working practices are cultural phenomena and how they are meaningful. However, cultural economy practices also indicate something about the contemporary nature of economic life, namely that we live in an era in which the economics has become thoroughly culturalized (Du Gay 1997, 4-5).

3.4. Consumption

Consumption is seen as an active process and often celebrated as a pleasure, and the consumer has even become elevated to the status of citizen, the principal means by which we participate in the politics. Cultural consumption is seen as the very material out of which we construct our identities: we become what we consume.

Symbolic goods function as signs and are used to signify. Culture is about the processes of identification and differentiation, with identities produced through practices of distinction. Consumption involves the consumption of signs and symbols of meanings and works like language in that it is rooted in a system of meaning. Consumption is the articulation of a sense of identity.

Consumers are almost endlessly creative in the appropriation and manipulation of consumer goods. Through everyday practices, goods and services are transformed, and identities are constituted. In a process of bricolage (construction or creation from a diverse range of available things), they appropriated, re-accented, rearticulated, or trans-coded the material of mass culture to their own end (Mackay 1997, 2-7).

3.5. Regulation

The regulation of culture in its broadest sense has become an arena of intense argument, debate, and contestation. A cultural artifact has an impact on the regulation of social life through the ways in which it is represented, the identities associated with it, and the articulation of its production and consumption.

Regulation has a number of meanings, depending on the context. It can refer to something as specific as government policies and regulations; at other times, it has a more general sense of the reproduction of a particular pattern and order of signifying practice, so that things appear to be ‘regular’ and/or ‘natural’.

The study of forms of regulation inevitably raises questions both of cultural policy by some regulating authority; and of cultural politics, involving struggles over meaning, values, forms of subjectivity, and identity. Regulation does not mechanically reproduce the status quo. It is a dynamic process that is often contested, and while the outcome is likely to be affected by economic pressures and power structures, it also depends on the specific circumstances and on the creative actions of individuals and groups (Thompson 1997, 2-3).

4. The Three Steps of Close Reading: The Method

These concepts will be applied in the breakdown of the close reading, but only some samples as prototypes could be loaded into the analysis. The working method goes through three steps, as follows: (1) the comparison between Mummy (1962) and Mummy (1968); (2) the examination of Afterlife Man (1970), as the publisher, part of the producer’s activity, refers to the mummy character in Mummy (1968); (3) the comparison between Oyi’s works, Mummy (1968), and two other titles from 1968, Almost Clashed and She-Wold, which showed a development in the politics of adaptation. Each step would be closed with a summary of an evaluation, which is going to provide the general evaluation before the conclusion.

5. Cultural Processes: The Analysis

5.1.Extra and Intra: From Mummy (1962) to Mummy (1968)

The picture-story Mummy (1962) by Jack Sparling is physically constructed from 31 pages of paper, plus two extra pages for the splash (title page) and a one-pager featuring fun facts about the pyramids. Each page of these 32 pages contains variations of four, five, or six panels to tell the story of Ahmed as a powerful mage in the service of the pharaoh.

With the advice of his ministers, this pharaoh wanted to bury Ahmed alive as a mummy because Ahmed’s magic power contested the pharaoh’s majestic image as a ruler. However, Ahmed’s resistance, with the power of the god Seth, leads to his return, centuries later, as The Mummy. It is his action of revenge in the modern day with his hypnotical power that became the spectacle of this picture-story, up until he actually died after falling from the top of a pyramid.

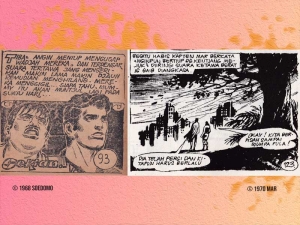

While the size of Mummy (1962) is 17 x 26 cm, Mummy (1968) is 19 x 11 cm. The difference in sizing makes Mummy (1968) adapt the former into a 93-page pocked-sized comic book with a variation of one to two panels for each page. The technical comparison goes like this:

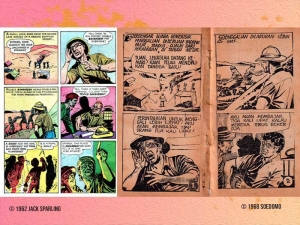

From 6 panels in 1 page to 4 panels in 2 pages.

As Mummy (1968) faithfully re-draws all 159 panels of Mummy (1962), it could be taken that, in the position of reader-creator, Mummy (1968) dominated all the signifying codes in Mummy (1962). Not only in the pictures, it also dominated in terms of the translation of English to Indonesian, with adjustments as the consequences of the different sizing of the panels of the books.

Faithfully redraw all the panels

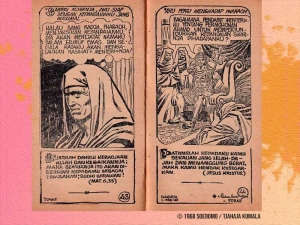

Besides the technical matter, however, the cultural matter shows a negotiation, even a subversion, to the dominant discourse from Mummy (1962), particularly when the pages come to the series of one panel for each page placement, because on each page, the extra-text, which is not part of the picture-story plot, is written.

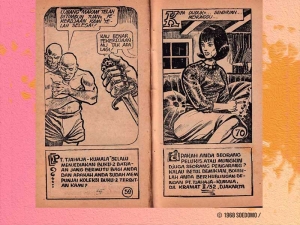

There are 19 one-panel pages, in which the extra-text could be divided into profane, personal advice, and sacred text. The extra-text samples are like these:

The profane extra-texts:

Tjahaja Kumala Company always provides quality books for you and do you already have books collection that we published?

Are you a painter or maybe an author? If it yes, you can contact Tjahaja Kumala Company, Djl. Kramat Raya II/32, Djakarta

The personal advice extra-texts:

The ultimate God bless is not the gift of abundant possessions, but the ultimate God bless is the serenity in life

Don’t you bow to wishful thinking, because they are just a show from shadows … but bow to your life, because it is life that makes you move, eat and drink, etc.

The sacred extra-texts:

First find the Kingdom of God and the Goodness; then everything will be given to you as an addition (Mat. 6, 33)

Come to me all of you which are so tired and bear the heavy burden, so that I can refresh you (Jesus Christ).

The mixed of profane and personal advice extra-texts:

That the truth is no grave hole can confine love

Greetings for artist friends at Pring-Gading Art Studio Tuban

Without life itself we can’t do anything

Greetings for all book readers and fans published by Tjahaja-Kumala Company.

Approximately only 9% of the 159 panels accommodate the extra-texts, but even if they are not part of the picture-story, they are part of the comic book that was consciously intended by the producer—they are still part of the subject that widens the discourse. In the case of this adaptation, the personal advice and the sacred extra-texts, whatever the real intention was, could be taken as a response to the text of the picture-story on the same page and to the whole idea of dark promises brought by the mummy that threaten the human soul.

Compared to the domination, as the redrawing of the pictures in all panels in the adaptation of Mummy (1962), these extra-texts in Mummy (1968) are presented as the position outside the domination, as if it is a strategy to avoid conflicts—a non-direct negotiation that functions as an active process of the consumer that rearticulated the source material as a producer.

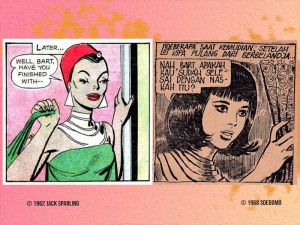

Mummy 1962 Mummy 1968

The same Egyptian women, the later adjusted for Indonesian public.

However, in the text itself, there is an act of adaptation that shows the authority of the consumer side on what is the better way to present for a different public. In the comparison of the two panels below, the two women are still the same Egyptian, but the latter showed what is going to be the acceptance of the public in Indonesia, as understood by the producer.

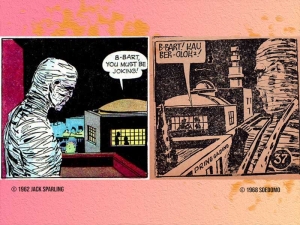

In another comparison below, it can be examined that the technical adaptation works from the point of view, which does not give any particular meaning. However, what is written on the wall, “PRING GADING”, cannot be interpreted only as a slight joke. On the contrary, it is legitimate as an act of cultural adaptation.

Mummy 1962 Mummy 1968

Not the technical adaptation on the point of view, but the cultural adaptation writes the word PRING GADING on a wall in Egypt.

From one of the extra-texts, it could be traced that Pring-Gading is the name of an art studio in Tuban, Indonesia. The same name on the text, not on extra-texts, makes the categorization problematic because the Mummy (1968) as an adaptation work never transforms the city in Egypt into a city anywhere in the world, especially not Tuban.

Consciously or unconsciously, the mixed codes of Tuban and Egypt are outside of the agreement on language translation from English to Indonesian. It became a cultural adaptation with all of the potential of appropriation, re-accentuation, rearticulation, or trans-coding of the material of the producer to the consumer’s own ideals. Consumption is not the end of a process but the beginning of another, and thus a form of production, which can refer to the work of consumption.

5.2. Constructing Identity: From Mummy (1968) to Afterlife Man

The surveyor will start with an artifact of assignment for the production of Afterlife Man (1970), which happened to be written behind the cover of Mummy (1968) like this:

Artefact of an assignment:

“AFTERLIFE MAN” (“MANUSIA ACHERAT”)

Number 1 to 3 (186 pages)

Occurrence in EGYPT

Characters CAPTAIN MAR (KAPTEN MAR)

and STAR PRINCESS (PUTERI BINTANG)

(look at the clothes and the shape and the agile

like the samples)

———————————————————

Make the face of the Mummy (Afterlife Man) more

and more scary and also grim

——————————————————-

picture size

20 x 28 cm

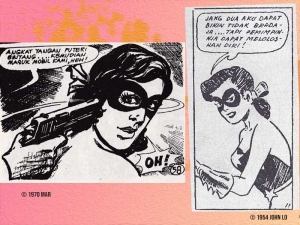

Being written behind the cover (the technical term is Cover 2) means that the writer of the assignment intended to use Mummy (1968) as the sample for the comic artist. As there are no samples of Captain Mar and Star Princess, those two local superheroes are presented here:

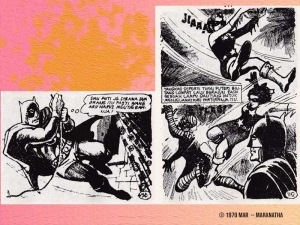

Captain Mar (Kapten Mar) and Star Princess (Puteri Bintang)

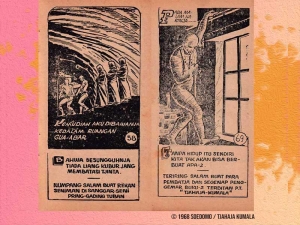

In Afterlife Man, the characters alone have already constructed the historic cultural network from a global perspective, while the setting for the plot is still Egypt. It is principally the same setting, with the same plot of the pharaoh’s victim buried alive and taking revenge on the descendent of the pharaoh until the fall as the ending, and the visually similar retelling of the related panels, this time combined with another plot in Cairo. In the capital of Egypt, the trouble made by the mummy inspired the criminals to act as a fake mummy, not to kill but to rob from house to house, which was later resolved by Captain Mar and Star Princess from Indonesia.

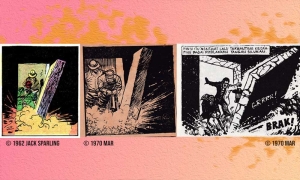

The similar ending of the two consumers as producers in the circuit of culture.

This is the case of how Mummy (1968) as a re-draw, which for a consumer seems to be dominated by Mummy (1962), in turn became the producer that generated a development in Afterlife Man with a similar plot, where the pictures transformed quite faithfully without knowing the first source. These similarities are balanced by differentiations, which, in a way, construct an identity of Afterlife Man, however inferior it is compared to the superiority of the dominant resource.

The facts are that only 16% of the whole 250 panels in Afterlife Man contain re-draws from Mummy (1968) panels, but it is the plot that absorbs the genuine developments, so that the title became Afterlife Man. However, it is the difference—the 210 new panels absorbed in the old plot, which even started with Mummy (1962)—that provided traces of identities.

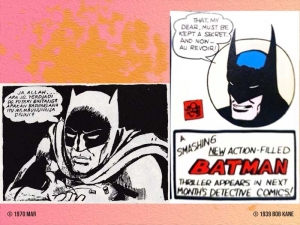

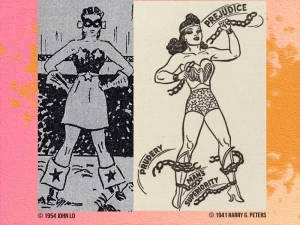

In the meantime, the examination of these traces will show that nothing is original. The main characters alone and each of their identities already represent multiple identities, as evidenced below:

Captain Mar (1970) referred to Batman (1939)

Star Princes by Mar (1970) refer to Star Princess by John Lo (1954)

Star Princess by John Lo (1954) refer to Wonder Woman by Harry G. Peters (1941).

As it could be traced, the character Captain Mar refers to Batman, the phenomenal commodification from a non-superhuman masked warrior, which in 1939 followed the footsteps of Superman—a one-night sensation as a commodity in 1938; while Puteri Bintang refers to Wonder Woman, which in itself consciously represents the feminist project of William Moulton Marston (1893-1947) that also became a phenomenal commodification of feminist ideology as a superheroine character in 1941.

Together with the Mummy (1962), which refers to the franchise of the mummy character in Hollywood movies, which started with the first one, The Mummy (Karl Freund, 1932), starring Boris Karloff, proved the construction of Afterlife Man as a nexus of historical economic achievement.

From Afterlife Man, it is important to note that as this picture-story refers only to Mummy (1968) and not Mummy (1962), as Star Princess 1970 to Star Princess 1954 and not Wonder Woman 1941, while Captain Mar is a direct combination of the ideas of Captain America and Batman, it shows how these processes work as a cultural process.

In this process, meaning is produced at economic sites, circulated through economic processes, and practiced as a cultural phenomenon. Through the cultural lens, economic practices become assemblages of meaningful practices, where production activity creates new meanings to construct new forms of work-based identity. As a work that consumes Mummy (1968), Afterlife Man is seen as being the very material that constructs identities.

Mummy 1962 Mummy 1968 Afterlife Man (1970)

The similarities had different meanings, depends on many factors in the circuit of culture.

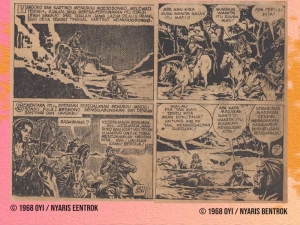

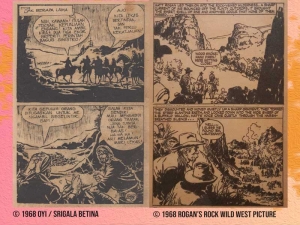

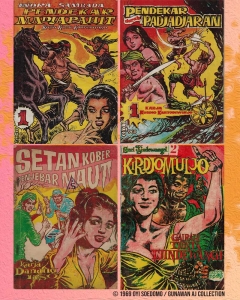

5.3 The Next Step of Adaptation: In the Shadow of Western Comics

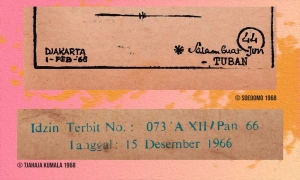

There are two titles of picture-story by Oyi, who is the same artist as Soedomo, who adapted Mummy (1962) to Mummy (1968). These two titles, Almost Clashed and She-Wolf, are also noted as the product of 1968, the same year as Mummy (1968), even when the legal permit noted it as from 1966.

Based on a date noted with hand signing from the greetings, arguably this Mummy by Soedomo is a 1968 product. The permit was given earlier in 1966.

What is important with this date is the fact that even though they are Oyi Soedomo’s works from the same year, one of them was the process of how the adaptation works. If in Mummy the adaptation is obviously dominated by the source, which is possible to prove from a direct page-to-page comparison, the two later titles seem to be difficult to liberate, at least from a visual domination, when the setting of the plot is in Java and the wardrobe is from traditional Javanese culture.

The different approach is applied here because, this time, the surveyor finds the signs and codes of the source from a close reading of the survey material. Before arriving at the end of the findings in this part, we need to know the story first.

Almost Clashed is about the conflict between farmers and cattlemen, with a romantic couple divided on each side, which is then interrupted by a third party. This story is composed of two parts: the first part is about the conflict that ended in peace and occupied 30 pages; and the second part is about the struggle of the couple that wants to be married but has an interest in the gold inherited by the girl. Fortunately, the bad intentions are stopped by the presence of Handoko Rekto, a wandering warrior.

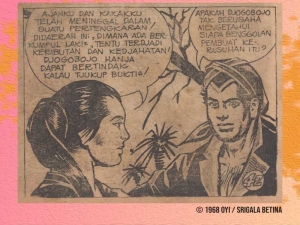

She-Wolf is about a dispute between cattlemen; one side is led by a woman warrior, as she inherited the cattle from her father. The other one is a young man who proposed to marry her with his eyes on her cattle but was rejected—he then terrorized her with the use of violence and some deception, too. With the help of Handoko Reko, her shortage of manpower could be resolved.

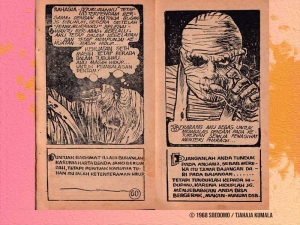

Examined as a case of adaptation, these two titles of picture-story describe the phenomenon in which, after the picture is transformed into another culture, the discourse that comes from the story is still embedded in the source, so that the new form is alienated from its own referred culture. Meanwhile, the discourse, even in a new language, is still translated discourse from the old one, so that culturally, it also does not match the represented culture.

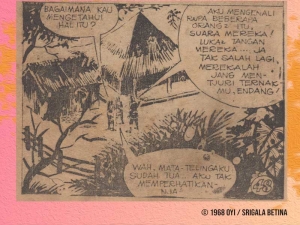

In these two titles, the plots play with one setting: the space that is mentioned as the place for farmers and cattlemen. In the pictures, all the characters wear the traditional clothes from Javanese culture, and because there are no dates at all, one could only roughly interpret that the time setting is approximately 19th century Java.

The consequences of being farmers in Java are the existence of farms, such as paddy fields, or something else, which is specific, such as sugar cane, tobacco, coffee, and indigo, that was ordered by Cultuurstelsel (the forced planting system by the Dutch colonial government), but there is no mention of this in the picture-story. Meanwhile, about the cattlemen, there are pictures of cows in a space that is not familiar, compared to the condition of Java in the 19th century, when the formal husbandry was established by the colonial government.

What happened is that the pictures resemble the Western comic genre, which started in the 1920s and was syndicated in 1927 in the United States.

Compare the cows (circles) as refer to Old Western vision

The pictures, then, eben in Javanese wardrobe, represent the discourse of Western comics, which means they are not adjusted to Javanese culture, such as discourse of marriage, trespassing, or about a security officer called djogoboyo, as known in rural Javanese villages at the time, but with the job description like a sheriff. In the pictures, the reader seldom finds a master panel of a village, while all the characters, including women, ride horses in the scenery that is more familiar to the Wild West than rural Java.

The job of “jogoboyo” discourse which refer to the job of “sheriff”

However, compared to the other adaptation project of the same artist, with Mummy (1968), these findings show the struggle in the cultural process and that in consuming the source, there are ways to develop an identity. From the genre of Western comics in America to the Javanese martial arts, there became a process of cultural hybridization, which also brought the process of learning, as culture does.

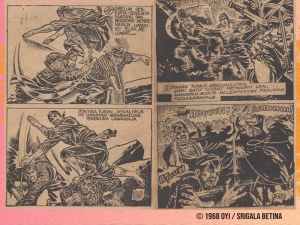

The typical scenes from martial art genre comics

Through the marking of difference, which takes place through symbolic systems and social exclusion, identity is forged to have a representational difference. The picture-story has an impact upon the regulation of social life as the articulation of its production and consumption.

The only two panels that showed a Javanese village, which is believable, compare to the dominant Wild West scenery.

More Wild West then Java.

The similar scenery of Java and Wild West showed that Almost Clashed (left) is an adaptation of a Western comic genre (right).

A life with horse that is uncommon, especially for woman with traditional clothe.

The logic of this narration could work only if the spare is a pistol.

6. Picture Stories as Representations: Evaluation and Conclusion

Mummy 1962 Afterlife Man (1970)

6.1. In the Trail of Adaptations: Evaluation

The evaluation starts with a presentation of Oyi Soedomo’s latest works in this survey, which are the pictures that show a liberation from the works before while establishing a solid identity after a long run, not of time, but of cultural process.

The covers of martial art stories created by Oyi.

Oyi Soedomo’s legacy: collector’s item.

From the preliminary finding, the surveyor noted that a faithful adaptation does not guarantee the same meaning would be transferred exactly like the source, especially when there are extra texts. Even though it only makes slight differences, it changes much from consumption to production.

After the comparisons, there are two moments of cultural process: (1) the simultaneity of consumption-production on the continuation of picture-stories adaptation from Mummy (1962) to Mummy (1968) to Almost Clashed and She-World in the same year of 1968; (2) the simultaneity of consumption-production on the continuation of picture-stories adaptation from Mummy (1962) to Mummy (1968) to Afterlife Man (1970) by Mar.

Taken as the same operation of the representational system, the continuation process is separated on the third stage: (1) the first one became the hybrid martial arts comic genre in question, Almost Clashed and She-Wolf, in the same year of 1968; (2) the second one still uses the mummy in the Afterlife Man (1970).

If the two titles, Almost Clashed and She-Wolf, even when the fine differences dominate the visual surface, do not process the discourse any changes, which makes the picture-story alienated from the cultural target intended in the transformation; Afterlife Man subordinated the new developed plot to the old one, and in doing so, made the differences the identity, even still using the same mummy.

6.2. Investigating Traces of Cultural Process: Conclusion

These cases of representational systems show how language, in written words and visual images as they were surveyed, is central to the production-consumption—and vice versa—process and the exchange of meanings between the members of society or group in the global world. On any representational form, as visual or written words, in combination, intermix, or fusion of the two, language is proven to be the key repository of cultural values and meaning.

Anything that appears regular and natural could be deconstructed from the source texts. It also means that an investigation of representations or signifying practices from traces in cultural processes could reveal political or ideological manipulation and disguise, consciously or unconsciously, in the history of adaptations, which constructs the contemporary world today.

——–

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cartmel, Deborah., Imelda Whelehan. 1999. From Text to Screen, From Screen to Text. London – New York: Routledge.

Du Gay, Paul (ed.). 1997. Production of Culture/Cultures of Production. London- Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Du Gay, et al. 1997. Doing Cultural Studies: The Story of Sony Walkman. London-Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Fleetway Publications. 1968. Rogan’s Rock. London: Fleetway Publications Limited.

Hall, Stuart (ed.). 1997. Representation: Cultural Representation and Signyfying Practices. London-Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Kane, Bob. 1990. Batman Archives Volume 1. New York: DC Comics.

Lepore, Jill. 2015. The Secret History of Wonder Woman. Melbourne – London: Scribe Publications.

Lo, John. 15 Januari 1954. “Puteri Bintang”. Madjalah Komik No. 2, Bandung: Penerbit Toko Melodie.

Mackay, Hugh (ed.). 1997. Consumption and Everyday Life. London-Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Mar. 1970. Manusia Acherat. Bandung: Maranatha.

Murray, Simone. 2008. “Materializing Adaptation Theory: The Adaptation Industry”. Literature/Film Quarterly Vol. 36, No. 1 (2008), pp. 4-20. Ithaca: Salisbury University.

Oyi. 1968. Njaris Bentrok. Djakarta: PT Tjahaja Kumala.

—————. Srigala Betina. Djakarta: PT Tjahaja Kumala.

Soedomo. 1968. Mummy. Djakarta: PT Tjahaja Kumala.

Sparling, Jack. 1962. “The Mummy” # 211 issue, September-November 1962. New York: Dell Publishing Movie Classics / mycomicshop.com

Thompson, Kenneth (ed.). 1997. Media and Cultural Regulation. London-Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Woodward, Kathryn (ed.). 1997. Identity and Difference. London-Thousand Oaks-New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

——-

*Seno Gumira Ajidarma, partikelir di Jakarta.